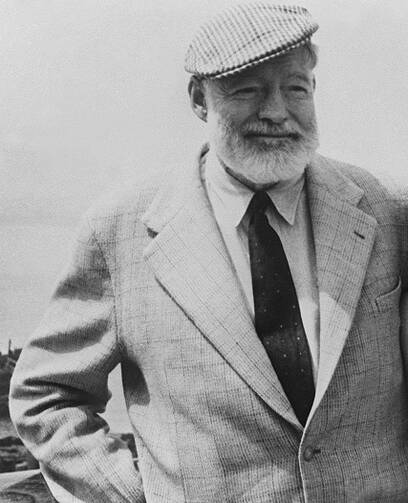

Fifty-four years ago, on a July day in 1961, the world awoke to the horrendous news that a giant of American literature had died at his own hand, from a shotgun blast to the head, just days short of his 62nd birthday. Only the world wasn’t told exactly that at first; the truth wouldn’t come out until much later. The official version was that he died from a mishap; that he had been killed from an accidental discharge from handling the weapon, possibly as he was cleaning it. The blast that emitted from that gun on that day in Ketchum, Idaho, not only ended a man’s life, but it also terminated the literary talents and gifts of the man the world had come to know as “Papa,” of a person who was literally larger than life and whose writings sought to capture the essence and the vitality of it—Ernest Hemingway.

Ernest Hemingway was born at the dawn of the 20th century, on July 21, 1899 and lived until he well passed that century’s midpoint when his death occurred on July 2, 1961. At the time of his death, there was a new president in the White House named John F. Kennedy, whose vitality and determination he admired—and which, in many ways, mirrored his own. He had been invited to attend the presidential inauguration, but by the time the new president was sworn on Jan. 20 of that year, the man and the writer named Ernest Hemingway was—as he thought and believed—past his prime, both physically and mentally. He did not—and could not—attend the inauguration of the man who reminded him of himself. The man who wrote so much and gave so much to American letters was literally wearing out, and unknown to him, hadn’t much time left, only the span of a few months.

Hemingway is familiar to all of us, particularly from our school days when he was required reading in our high school English Advanced Placement classes, particularly in his The Old Man and the Sea or perhaps others like The Sun Also Rises or ForWhom The Bell Tolls. His body of work included not only books of fiction but also works of reportage (for he was also an observer of current events) but he was also a diarist and a man of letters. His life was worthy of a book itself; his was a storied and adventurous life: married four times, he had three children and he traversed near and far, from Paris to Spain to the Florida Everglades and Cuba, from World War I Italy, to his various escapades in fishing, hunting and bullfighting. His life was the stuff of legends and great novels and yet he actually lived it. His life was a fascinating one, a poignant one and at the end, a sad one.

The man who was born in a Chicago suburb called Oak Park had an endlessly fascinating personality and given his inclinations, he could not help being so. Any man who could describe his hometown as a place of “large lawns and small minds” was sure to attract people to him with witty asides like that. With a curious mind and a talent for voluminous writing—plus a predisposition for adventure and derring-do—he would never be taken for an introvert and passive participant in the great journey that is life.

Perhaps this is why Ernest Hemingway is so interesting and why there are hardly anyone like him anymore—he was a writer, yes, but he was also a man—a vital man—who thought life a great adventure, not only to observe but to zestfully participate in. To be sure, there are great writers today; but in our time there are not any outsize personalities like the Hemingways of yore to speak of who made an impact upon our civic discourse. There was a time when writers were really considered a part of public life and what they said—apart from their books—mattered to us, causing us to pay attention and make people pause for thoughtful reflection and enter discussions and conversations of consequence. There was a time not that long ago when writers and journalists were considered as celebrities as much as the celebrities that came out from center field at the ballpark or the celluloid film at the theater. They attracted our attention and captured our imagination. They were in our magazines like Life and Look (the People magazines of their day) and when they really mattered, in others such as Time and Newsweek. And they also populated the talk shows of the time, running the gamut from a Jack Paar to Johnny Carson and to other talk/interview programs that had hosts like Merv Griffin to the seriously intellectually-minded, like a Dick Cavett or a Richard Heffner.

What is important to remember about writers like Ernest Hemingway is not the fact that they were outsize “celebrities”—which they were—but that they were artists of a fine craft; they were writers who put pen to paper and wrote about ourselves to ourselves, in the hope that we could read and ultimately, understand ourselves. Writing is no mean feat; it demands hard work and dedication and it is, you could truthfully say, a vocation. Even the New Testament tells us that “in the beginning was the Word.” Everything meaningful begins with a word and everything else flows from that. Writing and writers are often taken for granted, for they are so ubiquitous. They are always there whenever we want or need them. But we who are readers don’t always appreciate it—the work involved or indeed, the writer who brings these words to life for everyone to peruse, enjoy or treasure. For some, writing may come easily; for others, it comes at a cost. And in Hemingway’s case, the cost was his health.

In his lifetime, from the 1920s to the 1950s, Hemingway published seven novels, six short story collections and two non-fiction works and posthumously, three novels, four short-story collections, and three non-fiction works were published. Shortly before his death, he had been commissioned by Life magazine to write about Spain and bullfighting. He was enthused about the idea about going back to Spain and in a sense, relive his salad days. It was to be a pictorial essay, with photographs accompanying the text. He went to Spain, gathered research and formed his impressions and came back to write, but it became too much for him. In what should have been a manageable project soon spiraled out of control; he could not collect his thoughts. For the first time in his life, he could not finish what he set out to do. For a man of such gifts and talents, the realization that he could not complete his task must have been not only an embarrassment, but a humiliation. From then on, the man and his health declined. Physical health had a bearing on his productivity: by the dawn of the 1960s Hemingway had high blood pressure, liver disease (from years of heavy drinking), arteriosclerosis, failing eyesight and hemochromatosis (an inability to metabolize iron). He had begun to worry not only about his health, but about money and his safety as well. Hemingway the writer was besieged by his humanity and the bells he once wrote about began tolling for him. And in time, his health and his worries claimed him.

When he became the recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1954, he alluded to the dedication such a writing life demands and the costs it exacts. He wrote:

Writing, at its best, is a lonely life. Organizations for writers palliate the writer's loneliness but I doubt if they improve his writing. He grows in public stature as he sheds his loneliness and often his work deteriorates. For he does his work alone and if he is a good enough writer he must face eternity, or the lack of it, each day.

Ernest Hemingway knew the cost of the writing life; but he also knew the importance of it. Each day the writer in him faced the “eternity” of it as he reached for the pen and assembled his thoughts on those sheets of paper that lay in front of him. We must remember what he also said: “For a true writer each book should be a new beginning where he tries again for something that is beyond attainment. He should always try…” The writer and journalist who was born 116 years ago—and myriad others like him—who dare to write, deserve not only our thanks and gratitude, but also our appreciation. Our lives and our understanding would be all the poorer without them—and their words.