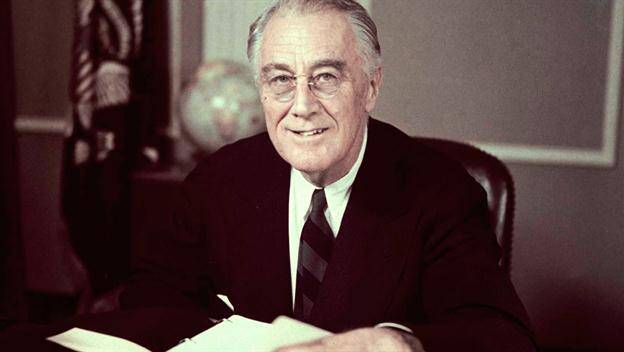

On April 12, 1945, an old man sat at a corner table that served as his desk and was reviewing papers and dispatches that needed his attention. He was only 63 years old, and by modern standards, wasn’t really considered “old.” But “old” he was—years of ill health and the rigors of his job took its toll on him and made him appear, and no doubt feel, much older than he was. His physical appearance belied his protestations of vigor: he had a grayish pallor about him and his eyes seemed to be sunken. His shirt collar did not fit correctly; there was an air of sluggishness about him. And all those years he battled poliomyelitis since the days of his young adulthood had taken its toll as well, leaving him to maneuver around in a wheel chair of his own devising. His incessant smoking and constant sinus infections did not help his medical condition either, but as so many of his generation did, he went on with life and did not let his obstacles—medical or otherwise—deter him from living life or pursuing his goals.

He had retreated to his beloved woodland cottage in Warm Springs, Georgia in order to recuperate and rejuvenate, as he had done so many times before, hoping that a change of scenery—not to mention attitude—would do the trick and bring back that jaunty countenance that was so familiar to countless numbers of Americans. And on a beautiful spring afternoon, he had plans and visions for the future; as the 32nd President of the United States, he was eager to see an end to world war and the future of a hopeful peace begin.

Only he never got the chance to live or see that peace. Franklin Delano Roosevelt—FDR to millions—had sat in his chair when he slapped the back of his neck and exclaimed that he had “a terrific headache” and peremptorily slumped forward, expiring from a cerebral hemorrhage.

Among those files of papers and documents that were laid out before him, was the text of an address that he had intended to deliver via radio broadcast for the next day, April 13, the anniversary of the birth of America’s third president, Thomas Jefferson. The intended remarks were for Jefferson Day or, as it was customarily known, the annual Jefferson-Jackson Day Dinner, which for those times, was the premier gathering and get-together of the Democratic Party, honoring both Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson.

At that time, the United States—and the world—have had to endure years of war thanks to the maniacal visions of Adolph Hitler. With the support the united nations of the world’s democracies, the freedom of the world was practically assured by the time of that spring day when FDR sat down to contemplate the future in Warm Springs. FDR had become concerned with our relations with the Soviet Union—a key war-time ally—and wondered how, not only to manage, but how to thwart Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin’s dreams of Communist dynasty in a post-war Europe. But that lay in the immediate future. For FDR, the task of the immediate present was to set the stage for peace and the practical details such a peace would demand.

The last few sentences spoke of his knowledge of the past and his hopes for the future, knowing how hard keeping a well-earned peace would be. He said: “…The work, my friends, is peace, more than an end of this war—and end to the beginning of all wars, yes, and end, forever, to this impractical, unrealistic settlement of the differences between governments by the mass killing of peoples…”

He continued: “Today, as we move against the terrible scourge of war—as we go forward toward the greatest contribution that any generation of human beings can make in the world—the contribution of lasting peace—I ask you to keep the faith…”

And he ended with the last words that he would ever write: “The only limit to our realization of tomorrow will be our doubts of today. Let us move forward with strong and active faith.”

Seven decades have now passed since FDR laid down his mantle as commander-in-chief, the man who led the nation through a Great Depression and a World War; even now, his beliefs, his actions—and his policies—still elicit great debate among historians and everyday Americans. That is as it should be.

But there can be no doubt that he was a leader in every sense—despite his human faults and foibles—but he had a determination that was rare. True, all who are politicians have that trait, we can see that with all of the candidates who ran for president this year—it would be impossible to be of the political species and not have that gene. But it is the rare president who is not only determined, but also innovative, forward-looking and positive. Those qualities are sorely lacking when they are not genuine and too many candidates—presidential and otherwise—strive for those heights and fail to reach that summit without possessing that genuineness.

At about this time of the afternoon back in 1945, the world slowly became aware that FDR had passed from the scene, leaving many uncertain, scared and unsure. He also left behind those words which were so American in character, about moving forward “with strong and active faith” and leaving doubt behind. Those are words that were very much needed then and ever more now, in our world of division, terrorism and discord. Some may say that FDR—to use his own words—was “impractical” and “unrealistic.” If that were really the case, the man—and the country he led—would never have achieved what they did in those seminal years.

His last words were a challenge that still echoes down through those decades, words that need to be heeded and followed by everyone, Democrat and Republican alike, but Americans all.