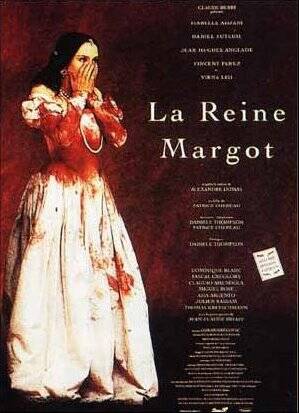

It has been years since I have seen a film as dazzling, beautiful and challenging as Patrice Chereau’s Queen Margot. It tell the story of the 16th-century French “wars of religion,” which raised to a bloody pitch with the Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre (1572) when, for various bad reasons, the Catholics of Paris and the rest of France slaughtered somewhere between 5,000 and 30,000 Protestants, depending how you count them. The Catholic website Unam Sanctam Catholicam offers the “reasonable estimate” of 9,000-10,000, with 2,000-3,000 in the city of Paris alone.

My head began to spin and my eyes strain in awe in the opening scene where Marguerite de Valois, Margot (Isabelle Adjani), the sister of King Charles IX (Jean-Hugues Anglade), against her wishes and at the command of her mother Catherine de Medici (Virna Lisi), marries Henri de Navarre (David Auteuil), the young Huguenot king of Navarre. The marriage, they believe or hope, will bring peace between France and Navarre. When the cardinal presiding at the ceremony asks Margot to express her consent, she stalls; her brother King Charles has to shove her face into the prie deux to get a “Oui.”

But cinematically the cathedral scene itself, with a battalion of bishops and cardinals in their blazing red and gold chasubles and gleaming white mitres, posed like a king’s army and towering Yankee Stadium bleachers on either side with thousands of faithful frozen in reverence, makes the recent scenes of a double canonization looks puny in comparison.

As it moved into its third hour a key scene reminded me that I had seen a shorter version of this film 10 years ago.

Meanwhile the sought-for peace unravels. Catherine has three sons (King Charles IX, Anjou and the youngest Alonson) plus daughter Margot. The action of the film rises from Catherine’s determination to secure the throne for her second son Anjou (all these young men are under the age of 20). This requires that Margot move south with her new husband to Navarre and that local rivals—some of whom, much to the anger of rabid Parisian Catholics, have been given roles in the government—be eliminated. She orders the assassination of Huguenot leader Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, who had been readmitted to the king’s council, and the murder of a large number of Huguenot leaders who have come to Paris for the celebration. All hell breaks loose. The thousands of citizens who in one minute were frolicking, singing, wrestling, drinking and dancing in the streets of Paris are in the next at war. Corpses naked, bloody, headless, stabbed, shot and piled high glut the streets of the city.

On her wedding night Margot refuses to sleep with her new husband and her own lover declines to sleep with her, so, wearing a mask, she wanders the streets and picks up a handsome young man, who happens to be a Protestant, for sex. Later he is almost killed in a sword fight with a Catholic; both collapse and their bodies are taken to a mass burial site where the young man, “La Mole,” (Vincent Perez) and his rival are discovered alive. Mole nurses his “enemy” back to life and they come to love one another as friends. And Mole and Margot become lovers.

In the midst of the slaughter, scheming and several poisonings (including arsenic-loaded lipstick where one kiss will dispatch a lover) the camera shifts to Henri of Navarre, who has been forced to give up his Protestant faith and become a Catholic. It is hard to escape the similarity of the story’s physical violence to the brutal intellectual coercion as the trembling young man—eventually to become king of all France—is made to recite the Creed. Later Henri joins Charles and his fellows for a horseback boar hunt, blessing the movie audience with extraordinarily beautiful footage as these graceful animals gallop through the forest enjoying the hunt as thoroughly as their riders and the dogs. Suddenly the king falls just as the wild boar is trapped. The boar is tearing him to shreds when Henri leaps to his rescue and kills the boar.

These men who casually order the deaths of hundreds for being of the “wrong” religion or members of the “wrong” family are beginning to think in terms of the value of human life. And not just their own. Margot, who had refused to sleep with her new husband begins to respect—and eventually love—him, while her love for Mole sensitizes her to horror of the war that her beloved family has pursued. And now King Charles IX clings to this widely scorned Henri with grateful affection.

Ironically Catherine de Medici has planned to remove Henri from the game of life by tainting the pages of a valuable book about hunting with arsenic so that Henry will moisten his fingers to turn the pages and unknowingly ingest the poison. Alas, her son the king reads the book first. He dies slowly, sweating blood that soaks his bedclothes, and wondering how he will answer God’s questions when they meet.

That is the one scene I vividly remember from 1994, but now with much footage restored “Queen Margot” speaks even more dramatically to today’s audience. The huge mass grave into which the St. Bartholomew victims are dumped is a foreshadowing of Auschwitz, My Lai and the graves being dug today in Syria. Great films try to teach and reteach us what far too often we forget.

"Queen Margot" will be showing May 9-May 16 at New York City's Film Forum and later this spring in Chicago and Miami (May 23), Columbus, Ohio (June 6) and Hartford, Conn. (June 13).