It was Shakespeare who said: “The evil that men do lives after them; the good is of interred with their bones.”

Though William Shakespeare often wrote in his dramas about the power plays of kings, the rich and the powerful, it’s too bad he didn’t live in a historical period a few hundred years in the future to see a monarch of sorts who would have really given him material to work with: Lyndon Baines Johnson, the 36th President of the United States. In Mr. Johnson, Mr. Shakespeare would have had it all, machinations galore, with all kinds of lust: for power, glory, fame, influence and immortality. He could have written scads of odes and sonnets about the man from the Texas Hill country who dared greatly at times and succeeded; and who failed spectacularly when it came to a war on the other side of the world, all because of pride, fear and hubris. To think of the plays the Bard could have written with that alone! (Oh, not that it hasn’t been tried: a playwright named Barbara Garson wrote a satirical one in 1967, called "MacBird!", applying Shakespearean elements laced with contemporary satire, with Stacy Keach and Rue McClanahan [later of Maude and Golden Girls fame] in the title roles and which closed after a limited run.)

The Bard’s thoughts about good and evil are quite applicable to Lyndon Johnson. He was a seminal president in our nation’s history; he assumed office in the most awful of circumstances: the assassination of his predecessor. It fell to his lot to lead the United States after John F. Kennedy, a Herculean task in imagination and in fact. Not that Johnson wasn’t prepared or didn’t have the skills—or the ambition. He had them in large quantities, Shakespearean quantities, in fact. He had spent a lifetime in politics: he had been a secretary to a congressman, got himself elected as a congressman, then a United States Senator and for a time, the Senate Majority Leader before ending up (as many thought, career-wise) as JFK’s Vice President. Then Dallas happened and Johnson found himself at the center of power for which he had craved his entire life.

If you know your American history, you know the rest of the story. His “finest moment,” if you can call it that, was when he became president in an uncertain and frightful time and slowly helped the country out of its grief in order to resume life. It took a lot of sensitivity and tact, attributes for which LBJ was not noted for. And the worst, of course, was the war—the Vietnam War—which, in the end, consumed not only his presidency, but the man himself. As he said in his earthy way, he had to ditch “the woman he loved,”—“The Great Society,”—in order to fight “that bitch of a war” that was Vietnam. But in between, he did a lot of other things that had great import upon American life and culture, things which reverberate to this day.

Lyndon Johnson was President of the United States for about 6 years, from November 1963 to January 1969. He left office when Richard Nixon was sworn in and that was 46 years ago. LBJ did not live long after that; he died in 1973, in the month when Mr. Nixon supposedly ended American involvement in the Vietnamese War that consumed his predecessor and when a controversial ruling on abortion was handed down by the Supreme Court. So, Lyndon Johnson has been dead for 42 years now, and is hardly remembered or spoken of. If he is spoken of at all, he is likely to be recalled or remembered for the Shakespearean “evils” he committed, not for whatever good he had done. Every once in a while, a new book about him will prop up and in a rare instance a play like "All the Way" with Bryan Cranston in the lead will capture an audience’s attention or a ubiquitous one-man show titled "Lyndon," with Laurence Luckinbill (Lucie Arnaz’ husband) will appear on public television.

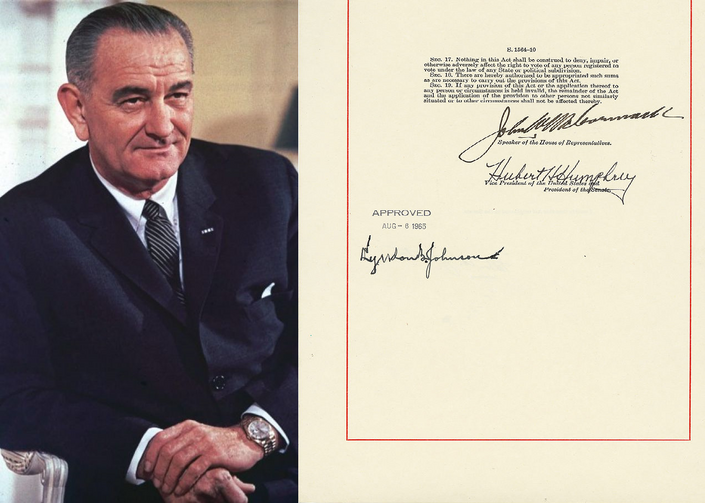

But in this year of historical anniversaries, there is one act of courage that Lyndon Johnson ought to be saluted and commemorated for and that was his work in getting the Voting Rights Act of 1965 through. He did not do it alone, though he was the gigantic force behind it; Democrats and Republicans, black men and white men all played their part in the passage of a bill that assured everyone of a very simple right in a democratic society: the right to vote. Voting is a very basic right and it is something we don’t always think about when we think of “rights.”

But it is at the top of the list and the most important one, for without it, nothing of consequence can happen: we cannot elect our leaders to represent us, we cannot decide what referendum should or shouldn’t pass, we cannot have our say in what course our town, city, state or country should take. The act of voting is a powerful one—one that is more powerful than the barrel of a gun—and unfortunately, not used as much. While Americans have the right to vote, they all too often exercise their right to complain. In modern day America, the reverse is also true: we have the right not to vote and that undermines the precious right that President Lyndon Johnson signed into “the books of law” on that day, so long ago now. He signed an act of Congress whose primary purpose was to ensure the right of every African American to vote—which was one of the crown jewels of the civil rights movement of the 1950’s and 1960’s, one that is being threatened today by all kinds of cynical legislative and political shenanigans by some who want to thwart that right to vote and disenfranchise a large segment of the American people.

People will have their opinions about the 36th President, about what he did and what he failed to do; but no one can dispute this great act, which among others, he signed into law. He signed it with hope, though he feared that it would be used someday to undermine the democracy he wanted the American people to have. But he did it anyway, believing in the future that is the American birthright.

It would be a shame that if Lyndon Johnson is to remembered at all, it would be for the earthier aspects of his personality or the way he pronounced “America.” Even he would admit he wasn’t a perfect man, but he really believed in a more perfect America and that the right to vote was a way to that perfection. Too bad there aren’t many leaders like that in the world today; leaders who aspire for the better instead of denigrating everything and everyone around them—if there were, people would happily vote for that.