The following case study of a university student will probably be familiar to many college faculty members and administrators: A young student from a “good Catholic family” of means arrives at a Catholic university to qualify himself for a comfortable position back home, arranged for by his family. He is bright enough, personable, good looking and a capable athlete. While he follows the requirements of the church, he “isn’t a fanatic” and tends to avoid those students too interested in excessive prayer or community service outreach. Studies, of course, are not a strain for him, though he generally spends more time with friends at games and the ubiquitous parties than with the books. Even his communications home are not surprising: “Thanks for the allowance. Send more money when you can. No, I’m not living as irresponsibly as you may have heard from recent visitors.” Even though the shortage of cash may have come from an occasional wager over a game of pool or cards, or from trying to live up to standards set by others’ expectations and might raise some eyebrows at home, he nevertheless remains within the normal parameters of the late adolescent/young adult seeking to find his identity in a world of new ideas. Yet the difference between passing through this stage onto a successful or meaningful future and ending up in the disastrous consequences of foolish choices often depends on the good or bad influence of friends.

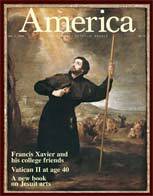

As the church and the Society of Jesus begin the celebration of the life anniversaries of St. Ignatius Loyola, St. Francis Xavier and Blessed Peter Faber, it is appropriate to look at the story of their meeting and discover how they became friends. If you have not recognized Francis Xavier in the above description, then you might want to peruse the first volume of Francis Xavier by Georg Schurhammer, S.J. (translated by M. Joseph Costelloe, S.J., Rome: IHSI, 1973). Before becoming the Apostle of the Indies and patron saint of missionaries, he had to pass through the vanities of his own world and find his particular vocation, with the help of a small group whose members came to call themselves “friends in the Lord.”

If Xavier’s school years resonate with modern university students today, the University of Paris and its challenges should not sound any less familiar to today’s university faculty and administration. The 1530’s at the University of Paris found the professors sharply divided over radical changes in the curriculum. The scholastic method of the late Middle Ages was being challenged by the “new learning” of Renaissance humanism, and the older faculty did not like it. Underlying this fight, however, was an even more difficult battle over the nature of the reform of the church and “the need to safeguard orthodoxy” in theology. Secret meetings and repressive inquiries brought censures and dismissals (just as often of the more outspoken conservative faculty). Not surprisingly, the local bishop opposed the naming of preachers at local parishes by the theology faculty of the university.

Students like Xavier could easily ignore most of this controversy, of course, even when they began their student teaching. More frightening for him, however, was a new disease called syphilis, still untreatable and eventually fatal, which had recently arrived from the Americas and frequently afflicted the more libertine students of the Latin Quarter. We know that Xavier enjoyed his occasional night out on the town, but he himself recalls that he was restrained from excesses as much by his great fear of the effects of this debilitating disease as by any moral qualms.

The choice of friends and professors, too, could have deadly consequences. Less than a year after Nicholas Cop, the rector of the university, had fled the country in the face of certain prosecution following his public address clearly siding with the Lutheran reform, Paris awoke to a concerted advertising campaign against the sacrament of the Eucharist and the Roman church. This affair of the placards, as it was called, in October 1534 once again threw the university and the city into a panic. The opponents of orthodoxy had even succeeded in placing a broadsheet on the king’s bedroom door! King Francis I ordered a public procession in reparation for this attack on the Blessed Sacrament, while royal authorities began to take more repressive measures, eventually burning many of those suspected to be sympathizers at the Place Maubert.

It is in this context that we must understand the importance of the friendships that grew around Ignatius Loyola and his companions at Paris. Certainly he and his companions knew the risks of living and studying in the midst of such turmoil. Friendships in times like these can often be difficult and call for a confident trust that is often hard to give. We know from Jerome Nadal, a fellow student approached by this same group but who initially rejected them, that they were surrounded by suspicion and rumors of heresy. Nadal stated that he avoided their company because he was sure they would all end up “in the flames.” In fact, Ignatius had been questioned and briefly imprisoned by the Inquisition in Spain, and hisSpiritual Exercises too came under examination in Paris as late as 1537. Ignatius was not a heretic, but the task of convincing his new companions to undertake a common program of service to the church with a goal no less optimistic than “helping souls” remained a struggle. While Xavier was willing enough to go to Ignatius for the occasional loan, he certainly avoided him when it came to spiritual and charitable practices. Besides, he had plans for his future back home. What, then, brought Xavier to warm to Ignatius’ friendship when others around him opted to stay away?

Xavier was initially acquainted not with Ignatius, but with his tutor, Peter Faber. The geniality and gentleness of the young Savoyard would not have threatened Xavier as much as the asceticism of his fellow Basque. But through Faber, Xavier was able to ask Ignatius for the financial support he needed at the beginning of his regency at Paris. The expenses for a young teacher in Paris were high, and Xavier’s family had been less forthcoming with money in the last few years. Ignatius also favored him by recommending students to him in order to increase his income through tuition fees. This financial aid must have earned Ignatius the right to engage Xavier in at least some gentle spiritual conversation.

The humanist professors who had been appointed to the university through royal favor and protection had easily attracted Xavier’s attention, but many in their circle were embracing the cause of Luther’s reform. (John Calvin, who had come to Paris from Orléans to study humanism, certainly inspired Cop’s famous speech. He too had fled Paris in 1533.) Ignatius would have known and discussed these academic issues with Xavier, for he had dissuaded another of the first companions, Nicolas Bobadilla, from following their courses. As the saying went, Qui graecizabant, lutherizabant (“those who study Greek become Lutherans”). From this warning came deeper discussions and perhaps even occasional confrontations concerning Xavier’s plans for his future and his need to secure the health of his immortal soul.

The growing company of friends (now seven) had also begun to coalesce around some common activities. In their studies they followed Ignatius’ counsel and attended theology courses with the more traditionally scholastic Dominicans at the College of St. Jacques. While they did not all live in the same residences, they would often meet at one or another’s rooms for spiritual conversation and prayer. They made their weekly walk to the Carthusian house at the outskirts of the city on Sundays in order to attend Mass and to confess and receive Communion more frequently than was the custom. Finally there was the capstone experience of theSpiritual Exercises, the monthlong silent retreat developed by Ignatius as a means of fostering interior conversion and making a better choice of life. Because of his teaching duties Xavier was unable to make the exercises until well after he had joined the group and pronounced vows with them in August of 1534.

When they had finished their studies, Xavier and the other companions traveled to Venice, where they met Ignatius, who had left Paris for Spain almost a year before them. Their time in Venice proved to be a practical preparation for their ordinations. By working with the poor in hospitals and teaching catechism to children, they learned a new way of being priests and ministering within the church. Once again Xavier came in contact with the harsh reality of syphilis. This time he tended to those dying of the dreaded disease in the Hospital for the Incurables. It was here that he was able finally to overcome his fear of disease and death, courage he would need for his future mission.

So their “friendship in the Lord” came to be based on their common experiences of study, prayer and service to the poor. When the companions finally came together in Rome during Lent of 1539 to discern their commitment to one another as a religious community, it was clear that their friendship had developed into something much stronger and more profound for the history of the church. Yet even while they prayed about their future together, they cared for many famine victims who had come to Rome because of the particularly harsh winter.

Before the company of friends had been transformed into a religious order, however, Xavier took leave of them and set off on a missionary journey that would take him from Rome and Portugal to Mozambique, India, Indonesia, Japan and finally to the coast of China. For 10 years (1542-52) he would cross the oceans and lands of Southern Asia preaching, baptizing and caring for the peoples of those regions. Despite his own personal doubts about his efficacy, Xavier pushed on from one new mission to the next. It was his constant search for new peoples to evangelize that brought him to the coast of China, where he died hoping to gain entry there. His death, alone and far from the friends who had brought him to that place, might appear to have been a failure, unless one considers how friendship can be maintained across great distances.

Their time of friendship together at Paris, Venice and Rome had caused a change within each one of these first Jesuits. Xavier would carry the autographs of all nine of his Paris companions on his missionary journeys, pinning them over his heart. But those friendships had already changed that heart; and just as each one of them was carried by Francis in his heart to the Indies, all of them remained in Ignatius’ and Faber’s hearts at Rome, in Jay’s heart in Germany, Rodrigues’ heart in Portugal and in the hearts of Salmeron and Bobadilla in Naples and Sicily. The companionship that freed Xavier to travel to the Indies in obedience could not be ended by their separation from one another. The letters of all the companions attest to that.

While it is usually the adventures and wanderlust that capture the imagination of most people who read about Xavier, it is his notion of friendship, his careful evaluation of what was truly important in his life and his ability to be freed by that friendship to “leave it all” at a moment’s notice that make him most accessible to the modern world. He was 19 when he arrived at the University of Paris and 23 when he met Ignatius, not far from the age of university students today. The lessons he and his companions learned in their school experiences together taught them about trust in God and in one another, gave them a sense of mutual accountability and bolstered a common interest in service to others.

These qualities remain goals for Jesuit schools in their mission to form men and women for others. By giving support and fostering life-giving friendships that help students grow in what the Lord asks of them, Xavier might just provide an inspiring historical case study for today’s young men and women.

Editor’s note: This is the first in a series of occasional articles for the jubilee year of the Society of Jesus, commemorating anniversaries in the lives of St. Ignatius Loyola, St. Francis Xavier and Blessed Peter Faber.