St. Francis de Sales produced an easily remembered description of the prayer practice, which Christians call meditation. You bring thoughts to mind in order to move your heart to God (Introduction to the Devout Life II, 5). Essentially, you give your mind some content, on which to chew, so as move your emotions toward God. The content might be sacred Scripture, a piece of religious art, a view in nature or even the events of your day. In meditation, you mull over something, and, doing so, you invite God to touch your feelings.

Back in the 70s, when bean bags and candles seemed essential to my meditation, I would put on an album like Jonathan Livingston Seagull and pray the rosary. It might not be what de Sales envisioned, but it met his definition of meditation: feeding the mind so as to move the heart to God.

Our tradition distinguishes meditation from contemplation. In meditation, the mind is active. In contemplation, it tries to coast. You simply want to be in the presence of God. The tradition also distinguishes between active and passive contemplation. In the former, you attempt to give your thoughts a rest. In the latter, God does this for you. You don’t even realize that time is passing. You’re only aware of God’s presence.

In “Amoris Laetitia,” Pope Francis writes that “fruitful love becomes a symbol of God’s inner life” (No. 11). There is an image of contemplation that is seared into my soul. It’s my last glimpse of my father alive. I was visiting home and had volunteered to celebrate Mass that morning in the parish. As I left our family’s home, I glanced into his bedroom. My father was sitting up in bed. Despite the morphine, he was in too much pain to lie back. My mother was sitting next to him on the bed, holding his hand. Two days earlier, she had had a mastectomy.

The image of them sitting in pain, sitting together, remains with me, like a pietà. They weren’t speaking; there wasn’t anything to say. Did either know that my father had only a few more minutes to live? At the end of Mass, I would learn that he had passed. Would there have been something to say if they had known? What more was there to talk about? They had passed a life in words and gestures, and shared experiences. Now, they were simply there. Together. That’s contemplation. And what happens with God isn’t all that different than what happens with others. With God or with others, it’s rare that we can slow down and gaze.

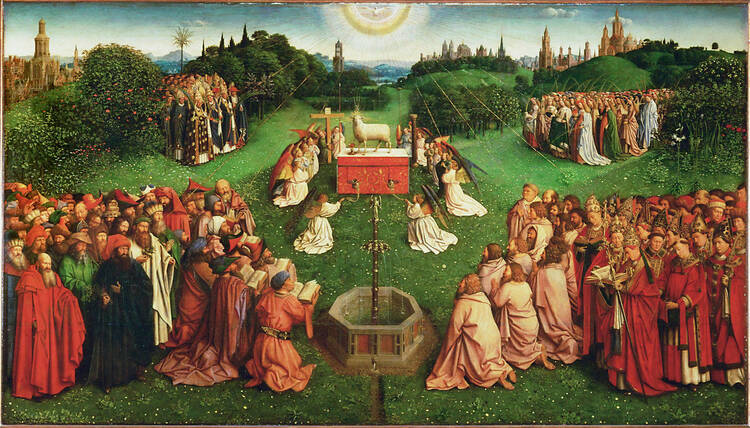

Scholars debate the source of St. John the Divine’s vision of the Lamb’s Court. Some suggest that early Christian worship was modeled upon John’s description. Others, that he was thinking of the liturgy as he wrote.

To stand before the Lamb is to contemplate, to coast. It’s gazing at another in love. John is describing a rest, a reward, which has been given to the faithful.

On this side of the grave, before the busy world is hushed, it’s very difficult, if not impossible, to imagine such tranquility. We cannot picture rest without restlessness. We pray “Eternal rest grant unto them, O Lord” and envision more respite than delight, because we cannot imagine living without bustle and burden.

When we think of liturgical prayer, when we consider what it means to pray at Mass, we can’t help but to envision something like meditation, a task to perform. And there is lots of content upon which to meditate. There are the words we hear, the gestures we observe the melodies, and the mosaic of sights we see: stained glass, statues of saints, Christ on the Cross. The Mass is a rich mine for meditation, but contemplation is its core, its true measure.

We don’t gather for Eucharist in order to do anything. We come to gaze upon each other, and upon the Lamb.

It’s difficult for us to gaze. It doesn’t come naturally. But there are graced moments in life when it steals over us. The mind falls silent because the heart is full. That’s what heaven is like. That’s what we seek, every time we hear the injunction, “Lift up your hearts.”

And then, though we haven’t yet earned the right, and our poor imaginations and memories have been wandering, we hear, in the utter grace of gift, “Behold the Lamb of God. Behold him who takes away the sins of the world. Blessed are those called to the Supper of the Lamb.”

Acts 13: 14, 43-52 Revelation 7:9, 14b-17 John 10: 27-30