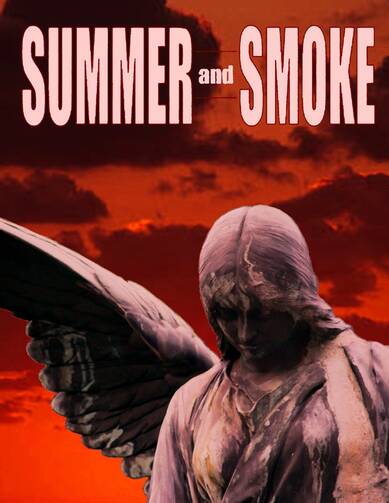

One of the most tragic, yet telling, lines in America theatre, is delivered at the end of Tennessee Williams’ play “Summer and Smoke.” Alma Winemiller, the fallen daughter of the local minister, in Glorious Hill, Miss., tries to seduce a travelling salesman. Poor Alma herself has travelled such a distance. Early in the play she argues with a sensual young physician, comparing the soul to a gothic cathedral in which “everything reaches up, how everything seem to be straining for something out of reach of stone—or human-fingers…all reaching up to something beyond attainment.”

But Alma’s faith has never really been tested. It’s easy for her to judge the young doctor as a shallow empiricist. By play’s end, she and the doctor have changed places. He’s convinced that he has a soul, while her final words bespeak her own most sorrowful need. Referring to her sleeping pills, she says “You’ll be surprised how infinitely merciful they are. The prescription number is 96841. I think of it as the telephone number for God.”

Last summer, in preparation for the church’s Jubilee Year of Mercy, Pope Francis gave an interview to the Italian journalist Andrea Tornielli, who asked him, “Why, in your opinion, is humanity so in need of mercy?” The Holy Father's response is published in The Name of God Is Mercy (2016).

Pope Francis suggests that much of our urgency for God’s mercy is our own inability to see our need for it. That is, of course, the nature of sin. It blinds us, confuses us, make the unreal seem right, acceptable.

The tender grace, the woeful beauty, of Alma’s last line is her recognition that she seeks mercy from an idol, from one of the many ways that modern men and women salve their souls. “You’ll be surprised how infinitely merciful they are. The prescription number is 96841. I think of it as the telephone number for God.”

Jesus comes to Capernaum to preach God’s mercy, but the people do not recognize their need for it. They want God to be manifested among them in power. They do not realize that their desire would reduce the living God to only one more power within the world, one which they can claim as their own. If only they would open themselves to him. If only they would look within and see the emptiness.

Francis says, “The first thing that comes to mind is the phrase, ‘I can’t take it anymore!’ You reach a point when you need to be understood, to be healed, to be made whole, forgiven” (31). Frustration can be a manifestation of sin, personal sin, because sin is a negation of God’s goodness, God’s life and power. If moderns no longer know what the word “sin” means, perhaps they should search their lives for frustration. It would help them find the wound.

The Holy Father recommends confession, saying,

“Alma” is Latin for “soul.” Tennessee Williams understood that her sin, her sorrow, was the story of the human race, seeking in frustration a solace that only God can give. “You’ll be surprised how infinitely merciful they are. The prescription number is 96841. I think of it as the telephone number for God.”

Jeremiah 1: 4-5, 17-19 1 Corinthians 12: 31-13:13 Luke 4: 21-34