One person touches another, and the consequences are far-reaching. Arriving at church an hour early, I enter the building. Despite reserved seating and rapidly filling pews, there is a space to the side and near the front with a good view, and I settle in.

The ordination of a new bishop coincides with a surprise visit from a traveling 20-year-old Australian cousin, and I had decided to make the three-hour journey from my small village to the bustle of the city to welcome, in different contexts, both of these people.

I sit among a gathering of the faithful in the church, along with a sizeable group of high-ranking church officials. Miters are lifted off and placed on heads at various points in the proceedings. I take note of the comforting presence of one monsignor, a dear friend better known as Father Charlie, as well as a bishop I once met on retreat at a monastery who now serves a vast northern diocese. These friendly faces beneath the miters and above the vestments help me to connect on a human level with this group.

The Face of Poverty

My cousin James and I encounter the kid wearing the black hooded sweatshirt when he taps on the car window, as we’re about to pull away from our parking spot close to the hostel. He wants a ride to Safeway, a distance of several blocks. My first reaction is to mumble to James, “I don’t really want him in the backseat of my car.” James responds, “Oh, you don’t?” Suddenly I feel ungenerous in my fear of this stranger. Grudgingly I allow the teenager to enter the enclave of the warm car. His face appears angular and pale to my sideways vision, and there is a scar or birthmark. Afterward, I remember his thin sweatshirt, suitable for a much warmer day. I realize how cold I am in spite of my wool scarf, thick coat and heavy hood. In contrast, he is ill-equipped to ward off the wind sweeping in from the icy lake.

A number of pews are reserved for diocesan priests, and I see familiar faces as well as guests of the bishop-elect. One pew is reserved for nuns, their number noticeably small. A couple of them wear traditional habits, but most do not. They greet each other warmly and seem to inhabit a small island in the sea of hierarchy. Other pews are reserved for schoolchildren and special guests. An air of anticipation fills the church.

In the car headed to Safeway, I say, “It’s cold.” The kid says, “Yeah, I wouldn’t want to sleep outside,” as though he often hunkers down in the street. His expression is inscrutable. For all I know, he bummed this ride to meet with his drug dealer. Or perhaps he is a drug dealer. I give my head a shake to dispel that scary thought. We pull up to the intersection beside Safeway, and he says, “It’s another couple of blocks.” I decide he’s lucky I allowed him in the car at all. I feel pushed to the edge of my comfort zone, and I will not go further. Employing my best mother-of-teenager’s voice, I firmly suggest he hop out, now.

It’s time for the new bishop to be blessed. One by one, his confreres approach their brother, their colleague, and each places hands upon the head of this man presenting himself humbly for ordination. The apostolic nuncio, an archbishop or two and one bishop after another steps forward. Each touch conveys a mixture of reverence and affection. I’m moved by an authentic sense of humility emanating from within the outward spectacle.

Then, unable to be contained within this group of honored men, it’s as if a generative, crucial essence within the ritual surges outward. I’m seized by a fierce desire to leap up from my anonymous place in the pew. I imagine racing up the stairs two at a time, to join with these shepherds of the church, to place my hands on the head of Brother John Corriveau in blessing. Does anyone else feel this undeniable summons?

As the young stranger opens the car door and gets one leg out, I blurt, “I’m sorry if I seem suspicious. I don’t know you at all....” The excuse peters out and sounds feeble to my ears. I feel frustrated and embarrassed, at an impossible distance from this nameless, unknown person. I feel helpless, and about as Christian as the imagined drug dealer.

A Gesture That Counts

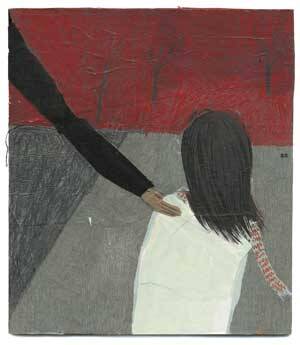

Suddenly, the kid turns back. He swiftly leans in. He grips my shoulder for one intense moment. Then he’s gone.

I suppose it isn’t for me to question a stranger’s motives, although clearly he wasn’t planning to buy groceries. In the face of my reluctant, half-hearted, blundering Christianity, this stranger touched—no, gripped—my shoulder. In that deliberate gesture, he assured me that I’m not so bad. He understood my fear and forgave me for it. This marginal stranger forgave me. He blessed me.

As a laywoman in the crowd gathered for the bishop’s ordination, I feel like Moses approaching the burning bush. Initial curiosity shifts to awe in the revelation of God’s certain presence in this place. It’s almost as astounding as feeling God’s unequivocal tenderness in the deliberate touch of a frightening stranger.