My paternal grandmother, Ruth, was the incarnation of hospitality for me throughout my childhood. As a perpetually hungry growing boy—eager for every fat, carb and casserole laced with cream of mushroom soup I could get my hands on—I developed a deep appreciation for Ruth’s talent for feeding the masses. Meals were always prepared with the possibility of unexpected guests in mind. Families with newborns could expect a steady stream of dinners for weeks. If Ruth learned of someone’s special fondness for a treat, that person could expect the craving to be soon satisfied from her kitchen. Starting when I was 8 years old, Ruth always checked to make sure I had enough bacon. I always had more than plenty.

Ruth died somewhat suddenly during my first week at college. Already homesick, adding grief to the emotional mix made for a difficult first month, marked by bouts of melancholy and tears. One day I alluded to these struggles while talking with my orientation leader, who also worked the front desk at my dorm. He listened sympathetically and then asked if I would like to participate in a program he led called Labre. Though I did not see it at the time, I now realize that he had invited me to cope with the sorrow of losing my grandmother by paying forward her greatest gift: hospitality.

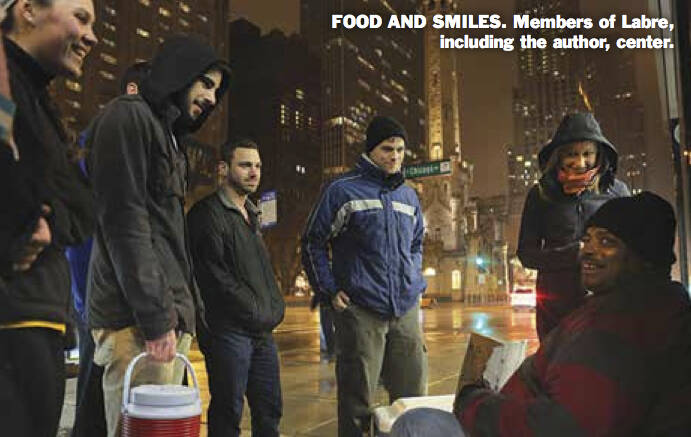

Labre is a student-led ministry to the homeless based at the downtown campus of Loyola University Chicago. In the spirit of its namesake, St. Benedict Joseph Labre, who in the 18th century took up the life of a beggar and shared all he had with the poor, students involved with the group seek to build solidarity and relationships with the homeless people on and around Michigan Ave. Food is prepared ahead of time and transported in wheeled coolers to be distributed to people living on the street.

But hospitality requires more than simply giving away food. Meals serve as a gateway to conversation and as a means of removing the veil of invisibility that social stigma often casts over homeless men and women. Labre’s strength lies in its comfort with what its mission is—and what it is not. It is essentially a ministry of mobile hospitality that seeks to ensure that the basic human dignity of a marginalized segment of the population is seen, heard and protected. Volunteers know that their humble offering will not end homelessness; but they also know that recognizing the humanity of each homeless person is the necessary first step in that mission.

Labre’s task is difficult. It is not simply a series of corporal acts of mercy at various spots along the streets of Chicago. Solidarity requires entering into the experiences of the people we meet, and these experiences are gritty, sometimes painful and often marked by various forms of ugliness. Some people exude optimism in defiance of their circumstances; others are understandably sullen and depressed. Jesus’ exhortation, “Whatever you did for one of these least brothers of mine, you did for me,” consistently strikes me as a greater challenge every time I encounter someone on the streets who describes losing a family member, or experiencing a debilitating injury, an addiction or some other horror that jars me from my own comfortable life.

It is not easy to encounter and embrace all who constitute the “least.” Unless I am running into someone I have met before, I still find the initial introduction awkward. We respectfully approach the individual—usually distinguished by a collection cup, a cardboard sign, battered shoes or a heap of blankets—trying to convey a friendly, unobtrusive presence. After an initial greeting, I typically ask the individual if he or she is hungry in an effort to transcend the economic divide—anyone can be hungry. Any preferred combination of hot dogs, granola bars and fruit is placed in a plastic bag and offered. Sometimes we have basic toiletry items or fresh socks, which are highly treasured.

As this exchange takes place, the conversation begins—starting with typical pleasantries and moving into the types of questions and answers that have surely dominated dinner party small talk from time immemorial. Every relationship begins from this same point. With those people we see repeatedly, these exchanges grow easier and cover a broader range of more personal topics.

But not all conversations lead to memorable fellowship or dynamic repartee. Some people we see once and never again. For every jovial encounter with someone just happy to talk, there is an uncomfortable, stilted conversation about the weather with a reticent person who can be any combination of tired, disheartened and embittered. It is from this reality that we learn that solidarity requires much more than empathy. To fully embrace the experiences of the homeless, solidarity requires surrender.

By acknowledging the limits of two hot dogs and a banana in the fight against extreme poverty—while offering them again and again anyway—Labre shows its strength. Surrendering to these limits is not a sign of weakness but an acceptance of the ultimate necessity for God in events and contingencies totally out of our control. It is easy to see the divine in a beautiful sunset, but it takes a measure of surrender to find God in cold and hunger. When I listen to a woman speak about suffering abuse from her husband, or a father’s struggle to consistently feed his children, I feel both a profound need to fix everything afflicting the streets of Chicago and an overwhelming sense of inadequacy in the face of these tragedies.

Just when I am prepared to work myself into a fatalist tizzy, I turn to the cooler. I surrender to God that which is beyond my control in order to direct my focus toward being present to the experience of the person in front of me. In the surrender, we find liberation. The food, the conversation, the moments of silence and the gusts of wind are all afforded grace because we get out of our own heads and allow God to fill the space.

The enormous, brightly lit buildings of Michigan Ave. flank our route, and their opulence blinds many passersby to the huddled figures beneath the display windows.These buildings have always reminded me of the walls of the Red Sea that lined the Israelites’ march to liberation from Egypt. Carting the cooler, we too walk intentionally, in search of freedom. We seek liberation to see God truly in all things and the ability to accept our own limits. We seek liberation from the need to fix and control so that we can better share in the stories of the people we meet.

My grandmother Ruth was a figure of liberation in her kitchen. She felt free enough to experiment constantly with new dishes and to offer whatever she had in whatever quantity was available to all guests—expected or not. She would chuckle at humorous stories, nod sympathetically to complaints and listen attentively while unassumingly pushing the food toward your plate. Above all, she listened without feeling the need to interrupt with an opinion, to offer a quick fix to a problem or even to ask many clarifying questions. She let the words and stories hang in the moment, unafraid of the uncontrollable, offering what she always had—food and a smile. This metaphorical Promised Land that was realized in Ruth’s kitchen and continues to be made manifest in Labre, holds the key to solidarity. We do what we can and offer up what we cannot.