If nothing else proves the malevolence of the Taliban, the events of Jan. 20, 2016 confirm the depths to which these fanatics have descended. On that date a small group of Taliban murdered innocent students and staff at Bacha Khan University in Charsadda, Pakistan, a fairly new university. The date was deliberately chosen. It was the 28th anniversary of the death of Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan (1890-1988), universally remembered as Bacha Khan—King of the Chiefs—after whom the university was named.

Bacha Khan had struggled over many decades for the education and independence of his own Pashtun people, and he did so heroically, and yet non-violently, in tandem with his great friend and fellow struggler, Mohandas Gandhi, the Mahatma. Twenty-eight years after Bacha Khan’s death under house arrest in Pakistan, the Muslim enemies of the peaceful Islam he propagated tried to assassinate Bacha Khan posthumously.

Undoubtedly the murderers would have described themselves as mujahidin, strugglers for the faith of Islam, would-be martyrs engaged in jihad. But Abdul Ghaffar Khan was the greatest mujahid of them all, and he never shed the blood of any other human being. Jihad is a verbal noun in Arabic designating one or another form of struggle: jihad al-akbar—the greater struggle that is asceticism, struggling against one’s own vices; and jihad al-asghar—the lesser struggle that is external battling for an Islamic cause. Bacha Khan was a man of the greater jihad.

Pakhtunistan, the homeland of the Pashtuns, is the ethnic area of southern Afghanistan today and what used to be called the Northwest Frontier Province of Pakistan (now the Khyber Pakhtunkwa Province). The most famous living Pashtun is probably Hamid Karzai, the former president of Afghanistan; the three most famous cities in the Pashtun cultural area are Kabul and Kandahar in Afghanistan and Peshawar in Pakistan. The Pashtuns are the largest ethnic group in Afghanistan and the second largest in Pakistan, although the latter population estimate may be controversial. All Pashtuns are Muslim and many, if not most of the Taliban, are Pashtuns. We Americans went to war with the Taliban nearly 15 years ago to try to extract from their protection a citizen of Saudi Arabia, the late Osama Bin Laden. Chief among the traditional virtues of Pashtuns is hospitality for and protection of guests, so they did not surrender Bin Laden very easily.

A Son of the Pashtuns

The Pashtun territory was divided more or less in half by Lt. Henry Durand in 1893 when, on behalf of the British Raj in India, Durand delineated a border between British India and independent Afghanistan. May I say, on behalf of my Irish ancestors, that partition is often the British solution to seemingly intractable problems: Ireland, India, Palestine. The Pashtuns, a warrior people not unlike the pre-Islamic Arabs, preserve down to modern times traditions of clan rivalry and revenge-taking. They have been Muslims for many centuries now, but their cultural proclivity to what they call (using a word derived from Arabic) badal—mutual blood-letting in revenge—continues to characterize Pashtun culture.

In 1890 Abdul Ghaffar Khan was born in the village of Utmanzai, the second son of a Pashtun notable, and he grew up imbued with the culture of his people, although his parents were also willing to expose him to Western and even Christian missionary education. Without ever becoming a Christian, Khan absorbed a lot from his secondary education at Edwardes Memorial Mission High School under the tutelage of the Reverend E. F. F. Wigram. One of the central lessons young Khan took from that school was the ideal of unselfish service to fellow human beings, especially in the promotion of basic education among the Pashtuns. The British did not react positively to the idea that education not controlled by them was good for the Pashtuns and Khan came into constant conflict with the colonial authorities after 1910, the year in which he opened his first school in his native village of Utmanzai.

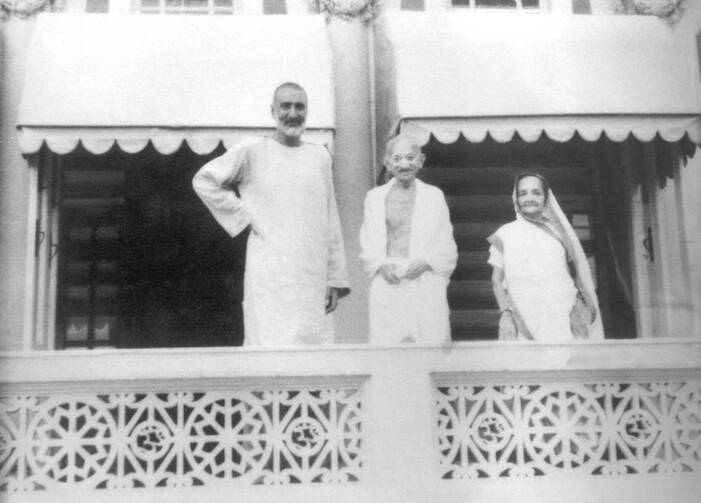

Newly a widower at the age of 25 in 1915, the year that Mohandas Gandhi returned from South Africa to India, Bacha Khan threw himself into his pioneering educational work. Bacha Khan first ncountered Gandhi in 1920 and he remained a faithful disciple and friend of Gandhi for the rest of his life. The British exiled him from Pashtun territory and he often spent time with the Mahatma in central India, campaigning nonviolently for Indian independence and for Hindu-Muslim solidarity. The partition of India and Pakistan in 1947 was for both Bacha Khan and the Mahatma an inestimable tragedy, mainly the work of rather secularist Muslims like Muhammad Ali Jinnah and secularist Hindus like Jawaharlal Nehru. Bacha Khan spent 30 years of his life in jail—15 before 1947 in British India and fifteen after 1947 in Pakistan. Although he swore allegiance to Pakistan, the authorities of that new nation never trusted Bacha Khan and he eventually became identified with an attempt to create a Pashtun state carved out of Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Rejecting Violence and Revenge

In the pre-independence era, starting in 1929, Bacha Khan had intimidated the British colonial authorities by creating a nonviolent, red-shirted army of his own normally rather violent fellow Pashtuns. That unarmed militia he called Khudai Khidmatgar, “God’s Servants.” Counterintuitive as it was, the oath of the Khudai Khidmatgar harnessed the militancy of the Pashtuns in a non-violent direction that many had previously thought impossible:

I am a Khudai Khidmatgar; and as God needs no service, but serving his creation is serving him, I promise to serve humanity in the name of God. I promise to refrain from violence and from taking revenge. I promise to forgive those who oppress me or treat me with cruelty. I promise to refrain from taking part in feuds and quarrels and from creating enmity. I promise to treat every Pashtun as my brother and friend. I promise to refrain from antisocial customs and practices. I promise to lead a simple life, to practice virtue and to refrain from evil. I promise to practice good manners and good behavior and not to lead a life of idleness. I promise to devote at least two hours a day to social work.

There were several notable demonstrations of Khudai Khidmatgar’s nonviolent resistance of continuing British occupation of India; the Khudai Khidmatgar kept their vow of nonviolence even when the panicked British military mowed them down with machine guns.

How did Bacha Khan justify such a nonviolent program in Islamic terms? More than once he used as an example for his fellow Pashtuns, and indeed for all Indian Muslims, the patience (sabr) exercised by Muhammad and the first Muslims as long as they remained in Mecca (610-622 AD). Such patience was ideally suited to a time and place when the Muslim community was a minority and challenged by a hostile majority. “There is nothing surprising,” Bacha Khan wrote, “in a Muslim or a Pashtun like me subscribing to the creed of nonviolence. It is not a new creed. It was followed fourteen hundred years ago by the prophet all the time he was in Mecca.”

Bacha Khan lived on well beyond his hero Gandhi, dying in Pakistan in his 98th year on Jan. 20, 1988. Honored in India, he was and is often despised in Pakistan, although the current government of Pakistan did name a university after him in 2012. At the end of his life he requested that he be buried at Jalalabad in Afghanistan, a symbol of his transnational vocation as the Bacha, or king, of the Pashtun people, no matter on what side of the Durand line they found themselves. War was raging in Afghanistan between the communist government, which was backed by the Soviet army, and the Western-backed mujahadin, the ancestors of today’s Taliban. Astonishingly, both sides declared a truce for the day of Bacha Khan’s burial, although the truce was marred by some explosions and violence.

Bacha Khan lived his long life to the end as a man of peace in a world of violence. God who is Rahman and Rahim, as Muslims always say before they pray—all-merciful and ever-merciful—will reward him and all peacemakers in the age to come. It was only suitable that Malala Yousafzai, the adolescent Nobel laureate and living martyr for girls’ education, mentioned Bacha Khan’s name among her heroes when she spoke before the United Nations in July 2013. Indeed, she continues the vocation of Bacha Khan on a world stage today:

I do not even hate the Talib who shot me. Even if there is a gun in my hand and he stands in front of me, I would not shoot him. This is the compassion that I have learnt from Muhammad, the prophet of mercy, Jesus Christ and the Lord Buddha. This is the legacy of change that I have inherited from Martin Luther King, Nelson Mandela and Muhammad Ali Jinnah. This is the philosophy of non-violence that I have learnt from Gandhiji, Bacha Khan and Mother Teresa. And this is the forgiveness that I have learnt from my mother and father. This is what my soul is telling me, be peaceful and love everyone.

The Taliban tried to kill Malala Yousafzai in 2012, and did not succeed. In 2016 they have tried to complete what the British and various Pakistani governments in the past tried to do to Bacha Khan, and they have not succeeded either. Bacha Khan and Malala Yousafzai have pioneered for all the world to see a humane and peace-loving vision of Islam that will triumph someday over those who are trying to smother its birth today.