For the hundreds of South Sudanese refugee children settled into a Ugandan camp, learning how to react without violence is as much a part of their schoolwork as academic pursuits.

The refugee families, who have fled two years of ethnic fighting in newly independent South Sudan, value the material the children are learning, but also want to see an end to the decades of conflict that has plagued their homeland.

So when Gabriel Chol, a teacher who fled the fighting as well, called the parents together and helped organize a school in the camp located in the Arua Diocese near the border with South Sudan, family members eagerly welcomed the initiative.

"We called all the elders, intellectuals and parents in the community and we shared our idea of setting up a school under the trees," Chol said.

Plans were made and soon people came with hoes and machetes to clear the ground, he said.

Diocesan leaders embraced the initiative and helped establish the School of Peace Primary Education with help from the Sant'Egidio Community, a Catholic group that runs social-service programs in Rome and assists in mediating political disputes in Africa and Eastern Europe.

Djaipi Parish, 18 miles from Uganda's border with South Sudan, has been a safe haven for refugees since fighting broke out in Juba, South Sudan's capital, between ethnic Dinka and Nuer in the presidential guard.

The conflict turned into an all-out war in which thousands of South Sudanese have been killed and about 2 million people have been forced to flee their homes.

The church and primary school served as an arrival center for refugees supervised by United Nations officials and other aid agencies. There were so many people that some slept in the open as well as in tents and on the rectory porches.

"The priests working in the parish lost their privacy completely as there were lots of people on their porches," said Bishop Sabino Ocan Odoki of Arua.

Children were "scattered without any organization," he said.

When Bishop Odoki visited Rome in March 2014 and told fellow members of the Sant'Egidio Community about the refugees' plight, the community resolved to fund a primary school.

While 28,000 children were ready to enroll, funds were available for teachers' salaries and other costs to cover a school for 1,000 pupils, Bishop Odoki said.

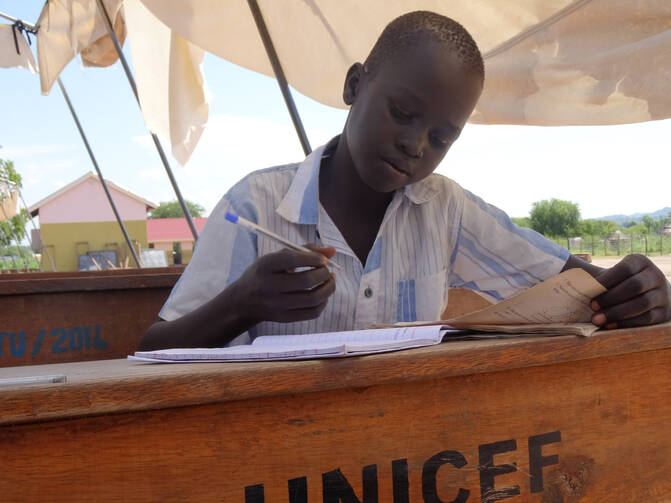

Teachers were recruited from among the refugees and the School of Peace Primary School opened.

There were large trees on the land allocated for the school and each class was organized under a tree, he said. Tents to shelter classes from rain and desks were obtained after a parents and teachers association was formed; Sant'Egidio has funded the building of four classrooms.

The number of children at the school continues to grow.

"Children are suffering" through missed schooling and there is a "great need to do more as long as the situation in South Sudan remains unstable," Bishop Odoki said.

Noting that the school is "emergency help," he said the diocese has no long term plans for the school.

Fifty-one percent of children between ages 6 and 15, about 1.8 million in all, do not attend school in South Sudan, the highest proportion in any country, the U.N. children's agency said Jan. 12.

Even before the latest conflict began, 1.4 million children were not at school, UNICEF reported. At least 400,000 children have left their classrooms and about 800 schools have been demolished during attacks in the past two years, the agency said.

Violence persists throughout South Sudan's government even though the factions signed a peace accord in August.

Abun Issa Zakeo, a Ugandan who is the school's principal, said that constant fighting among the children in class has been a difficult problem to overcome.

Parents and teachers were informed of Uganda's policies of violence-free schools and encouraged to talk to the children about appropriate behavior, he said. With the help of the Lutheran World Federation, counseling groups for children were organized and have reduced the number of violent incidents in the school, he said.

While the school lacks basic facilities, many parents have chosen to keep their children enrolled, foregoing the option of sending them to a better-resourced neighboring government school.

"We trust people of God. What they promise, they will do," John Achiek, a father of four children at the school, told Catholic News Service.

Another parent, Rebecca Agok, said that when "we came here, this place was a forest" and the diocesan authorities' decision to establish a school made parents happy and set them to work in preparation.

The children at the school take learning seriously because their parents have told them that nothing but education will help the people of South Sudan, said Chol, who is now deputy principal.

Parents regularly bring food for the teachers and are being asked for cash contributions for more shelters for the classes, he said.

The highest number of children in a class is 100, less than half the size of an average class in South Sudan, he said.