Adam Lord Gifford (1820–87), a philosophic man with considerable wealth, bequeathed to four universities in Scotland an endowment to support work regarding natural theology. For the more than 100 years since that gift, noted thinkers and writers have been drawn to Scotland to share their research and insights. Many of those lectures have been published; a number of them are considered classics in their field.

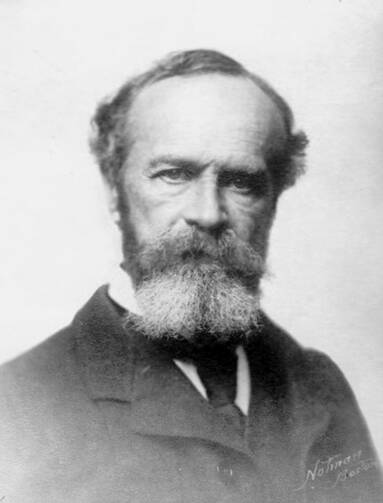

One of those classics is The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature, a series of 20 lectures delivered by William James at Edinburgh in 1901–2. James (1842–1910), a noted philosopher and psychologist—and brother of the novelist Henry James and son of the theologian Henry James Sr.—taught at Harvard for many years. Central to his thought was pragmatism as a major criterion for truth. His fluency in languages and his breadth of knowledge were extensive.

In The Varieties of Religious Experience, James deals with topics like saintliness, mysticism, conversion, the divided self and the sick and the healthy-minded soul. Using passages (often extreme and eccentric) from individuals who had religious experiences and wrote about them, James analyzes how the human spirit attempts to engage in the mystery of divine transcendence.

As I read and reread this classic, I am amazed at both the depth of knowledge and style of James’s writing, so many wonderful turns of phrases, so many wonderful insights not only into religious experiences but into life itself. Here are 10 insights from William James that have haunted me on my pilgrim journey. (Direct quotations from James are italicized.)

1. The human condition applies to everyone.

The sanest and best of us are of one clay with lunatics and prison inmates, and death finally runs the robustest of us down.

There is in life a universality; we are all in the same canoe. No one is exempt from weariness, from moral failure (sin), from psychological distress, from acedia, from physical, intellectual and spiritual limitations. We are all of the same clay. How that clay is shaped for good or ill depends upon our use of human freedom and the circumstances of our life and culture. But way down deep, we all, whether sane or crazy, whether free or incarcerated, will face diminishment and death. Compassion, therefore, seems to be the order of the day.

2. Our feelings affect our character.

Both thought and feeling are determinants of conduct, and the same conduct may be determined either by feeling or by thought. When we survey the whole field of religion, we find a great variety in the thoughts that have prevailed there; but the feelings on the one hand and the conduct on the other are almost always the same, for Stoic, Christian, and Buddhist saints are practically indistinguishable in their lives.

A great case can be made for orthodoxy, right thinking. The theater critic Walter Kerr reminds us: “An infection begun in the mind reaches every extremity.” And so it does. But James’s point is fascinating in his claim that among the really good people in history (called saints), their feelings and their behavior are essentially the same: lives of love, compassion and forgiveness would certainly be a partial description of their existence. But as for thought, how differently do believers and philosophers conceive of the world and, for that matter, truth. This being said, thoughts are tremendously important, as are feelings, in shaping our conduct. We might add to James’s determinants the significance of images and stories in shaping our inner life and our behavior.

3. Naturalism is not enough.

For naturalism, fed on recent cosmological speculations, mankind is in a position similar to that of a set of people living on a frozen lake surrounded by cliffs over which there is no escape, yet knowing that little by little the ice is melting, and the inevitable day drawing near when the last film of it will disappear, and to be drowned ignominiously will be the human creature’s portion. The merrier the skating, the warmer and the more sparkling the sun by day, and the ruddier the bonfires at night, the more poignant the sadness with which one must take in the meaning of the total situation.

In Dante’s Inferno, hell is not fire but ice, which makes any growth or motion impossible. For the naturalist, our world resembles a frozen lake that, though often offering experiences of merriment, nonetheless, in the end, offers only annihilation. No wonder that in the ancient tradition, melancholy was the eighth capital sin. Naturalism precludes a vision of a future life or, for that matter, any unseen reality that is the object of faith and worship. James captures brilliantly and with astounding emotion the plight of the human race devoid of any reality beyond time and space.

4. Saints are torchbearers, vivifiers and animators.

The saints, with their extravagance of human tenderness, are the great torch-bearers of this belief [sacredness of everyone], the tip of the wedge, the clearers of the darkness. Like the single drops which sparkle in the sun as they are flung far ahead of the advancing edge of a wave-crest or of a flood, they show the way and are forerunners. The world is not yet with them, so they often seem in the midst of the world’s affairs to be preposterous. Yet they are impregnators of the world, vivifiers and animators of potentialities of goodness which but for them would lie forever dormant. It is not possible to be quite as mean as we naturally are, when they have passed before us. One fire kindles another; and without that overtrust in human worth which they show, the rest of us would lie in spiritual stagnancy.

Certain individuals, graced with self-forgetfulness and committed to doing good, are known as holy people or saints. Their passion is to express love, to shed light on the dark world, to give life to those around them. James speaks of saints as “authors, auctores, increasers, of goodness.” Their radical conviction is that every person is sacred and merits not only respect but our active care. Because their lives are characterized by responsibility and generosity, they radiate a deep joy and peace. Would that all of us have the “overtrust” of the saints.

5. We need to address the big question.

What is human life’s chief concern?

In the end, what really matters on this complex, messy human journey? The philosopher Paul Tillich used the expression “ultimate concern.” William James provides a service simply by posing the question in such a succinct and direct manner. Our concerns in life are many: physical well-being, political stability, economic security, educational opportunities, enduring and endearing relationships. The list goes on. But as for putting first things first, what is it that resides on the top of our own agenda? Within the Christian tradition, the chief concern has been union with God and unity among ourselves. It was that unity and union that offered a modicum of peace and joy.

6. We are all susceptible to something.

Mankind is susceptible and suggestible in opposite directions, and the rivalry of influences is unsleeping.

Some individuals are gullible, ready to accept any idea or conduct of life. Without doubt, everyone is susceptible to a certain degree, everyone is suggestible up to a point. What we pay attention to shapes our days. What makes life and decision-making so difficult is that we are all surrounded by thousands of influences, whether from social media or the family system, from a third-grade teacher or a university professor, from the latest book we’ve read or the editorial in the morning paper. And, of course, these many voices often contradict one another. What’s a person to do? Here enters the art of discernment, sorting out wherein the truth lies. Throughout his life James sought to ferret out the truth of life and human nature.

7. We must make God our business.

We and God have business with each other; and in opening ourselves to his influence our deepest destiny is fulfilled.

Speaking of influences, how does the human spirit open itself to the divine with whom it has business? Does God speak to humankind and in what fashion? Some would posit that we encounter the divine in sacred writings (Scripture), others that God speaks through the community and daily experiences. Still others maintain that it is in the inner recesses of our being, the domain of the unconscious (dreams, etc.) that God will make the divine presence felt. James is concerned about our “deepest destiny.” If there are no transactions between God and the human spirit, the ballgame is over.

8. Appearances can be deceiving.

The roots of a man’s virtue are inaccessible to us. No appearances whatever are infallible proofs of grace. Our practice is the only sure evidence, even to ourselves, that we are genuinely Christians.

One of the characteristics of our human spirit is its inaccessibility. We smile looking back on the 1930 detective story “The Shadow.” “Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men? The Shadow knows!” This invisible crime fighter makes a claim that few psychologists or philosophers would have the arrogance to make. Appearances do not reveal all; our inner virtues and vices are buried deep. In his conviction that truth is found in pragmatism, James asserts that our deeds and conduct demonstrate whether our claim to be Christian is verified. Indeed, such is the position of the Last Judgment scene in Matthew’s Gospel. The sheep and goats are separated according to what they did or did not do to others.

9. We must choose the keynote of our own lives.

No fact in human nature is more characteristic than its willingness to live on a chance. The existence of the chance makes the difference, as Edmund Gurney says, between a life of which the keynote is resignation and a life of which the keynote is hope.

Moses placed before his people a choice: life or death. We have before us resignation or hope, love or hate, joy or sadness. People of hope look to the future with a sense of possibility. They are ready to risk and take a chance without knowing for certain what awaits them. People of hope have an abiding sense of trust and have the ability to buy into a promise. The other option is not appealing: blind resignation. What will be will be. Emily Dickinson said that hope is “the thing with feathers.” Woody Allen’s book Without Feathers calls out to the resigned people, not the hopeful ones.

10. Laughter expands the soul.

Even the momentary expansion of the soul in laughter is, to however slight an extent, a religious exercise.

In her autobiography, Story of a Soul, St. Thérèse of Lisieux speaks of the contraction and expansion of her inner being. For her, God’s grace caused expansion and great vitality, whereas contraction brought a narrowing of life and was not a sign of God’s Spirit. If it is true that laughter (not ridicule or scorn) expands the soul and offers emancipation, then it might well be characterized as a religious experience. Even a diminished laughter, the smile, might well be in the same category and an instrument of grace. G. K. Chesterton writes in The Everlasting Man: “Alone among the animals, [man] is shaken with the beautiful madness called laughter; as if he had caught sight of some secret in the very shape of the universe hidden from the universe itself.”

William James pondered not only the mystery of the human person but also the possibility that there is a God who was mindful of the creature so wondrously made. To reflect upon those ponderings might give us some insight into our own human nature and how God intervenes in human affairs.