Why do you return to your former parish in El Salvador every year or two?

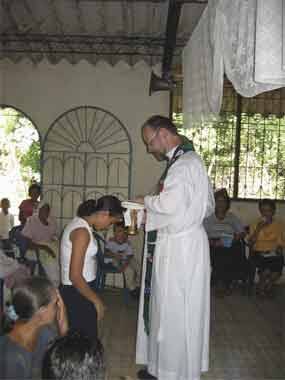

When I go back, it is not only to teach a theology course at the Jesuit-sponsored university there, but to minister again on weekends at the parish of Jayaque in the countryside, whose pastor—Ignacio Martín Baró—was one of the six Jesuits and two laywomen murdered by the military in 1989, just as Archbishop Romero had been murdered by members of the military in 1980. In the parish, I continue to experience the mystery of salvation as arising from the poor, which was one of the truths that Archbishop Romero—referred to in El Salvador as Monseñor Romero—came to understand so deeply.

Despite the danger of the military offensive, the parishioners came to Father Martín Baró’s funeral Mass. Afterward, they said to me, “You are now our pastor.” I was nervous at the thought of taking on this responsibility, but the Central American provincial superior supported the idea, and I stayed until 1991. It was a difficult time, particularly during the first weeks after the murders, when the army arrested and tortured some of our parish leaders. I especially remember a parishioner named Teresa. She stood up one day and said, recalling Father Martín Baró, “If they kill us because of what we are doing, I say welcome to death.” For the people of the parish, he was truly a martyr, just as Romero was.

How did you first hear of Archbishop Romero?

As a Jesuit scholastic, I worked for a time at the magazine Orientierung, which is published by the Swiss Jesuits. The editor in chief, Ludwig Kaufmann, had written about three people of outstanding faith. Romero was one of them. Reading about his life, I was deeply impressed not only by the fact that he was killed while celebrating the Eucharist, but also by the change that took place in him from being an anxious, conservative man to an outspoken advocate for the poor. The change began soon after he became archbishop, when his close friend, the Jesuit Rutilio Grande, was killed in 1977 by the military in the town of Aguilares because of his work with poor campesinos. After the death of Rutilio, Romero began to put into practice what is called the option for the poor—the thrust of the 1968 conference of Latin American bishops held in Medellín, Colombia. Eventually, Romero became an extraordinary prophet of the church of the poor, one who believed that his lived contact with them was the most important grace of his life.

When you finished your doctoral dissertation in 1992, did you return to El Salvador?

I wanted to, but it was the time of the civil war in the former Yugoslavia, and I was asked to be part of a team of Jesuits involved in a humanitarian mission there. In 1993, it became clear to me that if I were to take seriously the option for the poor, for the victims, I had to do something for the victims of that war in the Balkans. With money from German donors, we bought medicine and food for the people. We also began a scholarship program for students who, as refugees, had no means of continuing their studies. The only condition for receiving a scholarship was to try to show that the different ethnic groups—Serbs, Muslims and Croatians—could live together. The archbishop of Sarajevo, Croatia, at the time, Vinko Puljic, had tried to work for reconciliation, but he was criticized even by the Croatians who did not want to talk to the Serbs or the Muslims. I told him about Romero, who also had tried to work for justice and reconciliation. Later, when my book on Romero was translated into Croatian, I sent him a copy.

During a stay in Sarajevo, our team was living in the former seminary. The seminarians had all left. A whole collection of pianos had been stored there by people who hoped they would be safe. As a musician (I have a degree in music, and in Paris I studied organ with the organist of Notre Dame), I hesitated about playing on any of those pianos, given the terrible war situation that prevailed. But a Dutch Jesuit on our team reminded me of Dostoevsky’s famous phrase, “The world will be saved by beauty,” so I did play. It was a deeply moving experience.

Is the gap between rich and poor in El Salvador still as great as it was in the 1970’s?

Historically, the oligarchy was made up primarily of big landowners, and that is still true, although now its members are also involved in trade and banking. But the gap between rich and poor is the same, perhaps even wider. If I ask people in my parish in El Salvador how they compare the situation now with what it was like during the civil war, they say not only that they see no improvement, but that living conditions are actually worse. One indicator is the violence—an average of almost a dozen people are killed daily. Another indicator is that out of a population of six million, over 400 people daily try to leave the country to go the United States. I have a deep conviction from my experience in El Salvador that salvation must come through the poor. This is also the belief of my friend there, the Jesuit theologian Jon Sobrino. My doctoral dissertation was on the theology of Sobrino and one of the slain Jesuits, Ignacio Ellacuría (Sobrino was out of the country at the time of the murders). The title of the dissertation is “A Theology of the Crucified People.”

Part of your Jesuit training took you to India. What did you do there?

For six weeks I traveled around the country to speak with Dalit activists. The Dalits are a marginalized segment of the population who have long been denied their human rights. With 150 million people, they represent the world’s largest minority. I could see a connection between liberation theology in Latin America and the oppression of the Dalits in India. The uniting principle involves taking the perspective of the poor, of the victims, to discover that theirs is the perspective of Jesus himself. It entails a movement from above to below, what St. Paul calls kenosis in Phil 2:6, where he says that “Jesus emptied himself and took upon himself the form of a slave.”

The thrust of kenosis is to go from riches to poverty, from power to powerlessness. For me, any Christian theology has to give a central place to this truth. One of my main motives in entering the Jesuit order was a desire to work for justice for the poor. I am from a family that, though not rich, had everything in terms of material comforts. My grandfather had a dental clinic, which he wanted me to take over. But the story of Jesus’ call to the rich young man pointed to what I was seeking, and that led to the roots of my vocation. So again, the story of Romero is also the story of Jesus. In Matthew 25 he speaks of the need to recognize in the faces of the hungry, the imprisoned, his own face. For me, that makes it clear that the option for the poor has its basis in Scripture.

Pope John Paul II changed his opinion of Romero. What caused it?

The change came when the pope heard that Romero had been killed while celebrating the Eucharist. As he put it later, he felt that he had been killed for being faithful to the Gospel, and not for the political reasons that some had tried to attribute to him, and still do. I got this information from Cardinal Walter Kasper, who was on the committee that was preparing the Jubilee 2000 celebration to remember the martyrs of the 20th century. Cardinal Kasper told me that when the pope was presented with the list of the martyrs who were to be commemorated, he noticed that Romero’s name was missing. The pope then insisted it be added, because Romero died for his faith. In the final text Romero’s name was there.

Do the ordinary people in El Salvador regard Romero as a saint?

If you ask the ordinary people—as I did in preparing a German radio program—they always say yes, Romero was a saint. When you ask why, they say because he told the truth and spoke out in our defense. A saint is a person who thinks most of others, and least of him- or herself. Romero gave himself totally to his people, especially the poorest. The Arena party of Roberto D’Aubuisson—whom the U.N. Truth Commission showed to be the real person behind the assassination—this past February tried to have D’Aubuisson honored as a hijo meritissimo de la patria, “highly honored son of the nation.” But the people demonstrated against this move in front of the National Assembly, so the idea was dropped. They wanted Romero to be given this title, but the Arena Party would not allow it.

Speaking at America House in March, you referred to the theology of friendship with the poor. Please expand on that.

In a special issue of Stimmen der Zeit for the 2006 Ignatian anniversaries of Ignatius Loyola, Peter Faber and Francis Xavier, I wrote an article on being friends in the Lord—an allusion to the term Ignatius used for the first group of Jesuits. My idea was to link this theme with the option for the poor. Ignatius himself did this in a famous letter to the Jesuits in Padua, who were experiencing economic hardship. He told them it is the poor who make us friends of the eternal king. Ignatius’ idea was that if we make ourselves friends with the poor, we also make ourselves friends with Jesus. From a theological perspective, you can again base that on Matthew 25, in terms of those with whom Jesus especially identified. So the option for the poor, as expressed in the 1968 Medellín conference, is not new. Rather, it brings us back to the roots of the society that Ignatius founded.

You also mentioned the German theologian Johann Baptist Metz’s thoughts on poverty and injustice.

For the past few years, Metz has given a central place in his theology to compassion, as a form of sensitivity to the suffering of others. In that context, he refers to the claim, or authority, of those who suffer (the German term is Autorität der Leidenden). It is a claim closely related to the option for the poor, a claim that suffering demands for itself. You find the theme in the story of the Good Samaritan in Luke 10:33—the story of the traveler who, though belonging to a marginalized group, feels compassion for another traveler who had been attacked by robbers on the road between Jericho and Jerusalem. Left lying on the side of the road, the wounded man is ignored by others passing by. And this attitude is similar to what Romero felt: that in focusing on the marginalized and oppressed people of El Salvador, he was in close touch with the Lord.

The same claim has parallels with people who suffer from AIDS. Such suffering represents a challenge for the church, a call to minister to them in their affliction. I was very impressed by a book called The Body of Christ Has AIDS. Again, the fundamental idea is to identify with the suffering of Christ through those with AIDS. This past January I was in Africa at the World Forum on Theology and Liberation in Nairobi, where there is a Jesuit-sponsored AIDS network. A first step [of their work] is to bring the disease to a greater degree of consciousness and accept it as a reality. Jon Sobrino speaks in his writings of la honradez de la realidad, which means being truthful in the face of a painful reality.

I think there is a global tendency to close our eyes to the reality of suffering in this and in other areas, for instance, the inequality of the distribution of wealth. It is unconscionable that we live in a world order (in fact, a form of disorder) with two-thirds of the global population living in very poor conditions, while a fifth lives comfortably. A few months before he died, Ignacio Ellacuría called for what he termed “a civilization of shared austerity.” I believe that is the way we must go. It is a lesson we can learn only from the poor, because they are closer to that concept of shared austerity than people with wealth.

What is happening to minorities in your native Germany?

The official German policy is to restrict their numbers and, even if they entered legally, to expel them. One of the gravest injustices occurs when the police arrest immigrants with no legal status. They are imprisoned, sometimes for many months even though they have committed no crime, and are eventually deported. One good initiative taken by the German churches has been to speak out in defense of immigrants’ human rights, whether they are in Germany legally or not. Human rights are unconditional; every human being is a bearer of them. The German Catholic bishops now finance a special secretariat to help undocumented immigrants.

In Germany I stay in touch with the struggles of other marginalized groups too. Once or twice a month I celebrate Mass for the Brothers and Sisters of St. Benedict Joseph Labre, in a house somewhat similar to the Catholic Worker houses of hospitality, where poor people are welcomed. After the Mass I stay to play cards with them.

After our conversation, I asked Father Maier if he would like to have supper the next evening with the poor residents of the St. Joseph Catholic Worker on the Lower East Side of Manhattan and celebrate Mass for them. “Yes,” he said, “this is what I am looking for.”