Theology has many sources: Sacred Scripture, of course, and church decrees; documents from popes and councils, and the writings of saints; reflections on experience and insights into things beyond.

The epic poet Homer was called a theologian because he sang of gods and their ways, of heroes and scoundrels, of loyalty and betrayal. Numerous book titles include “A Theology of,” with the object being St. Augustine or Samuel Beckett, the body or holiness or hope, liberation or time or the icon. Perhaps more ironically, America’s pages have talked of the theology of Louis C. K. (8/17/15) and of Taylor Swift (6/6/16); The Jesuit Post entered the list with “Lady Gaga the Theologian” (5//11/16). Meanwhile, The New York Times has given us “Obama the Theologian” (2/8/14) and “The Theology of Donald Trump” (7/5/16).

While it might not be necessary to say there is “a theology of James Lee Burke,” the crime novelist certainly has insights into the ways of God as they relate to the ways of his heroes and villains. His 37 novels and two short-story collections have built up a faithful readership that relishes the struggles of those who would do good in a context of pervasive evil. Sometimes the religious angle is explicit. More often it is dropped in subtly or casually, along with historical, literary and artistic references and insightful glimpses of the world of nature. Sometimes it is in simple references to medals, statues, Communion hosts.

In 37 novels and two short story collections, Burke writes about characters who struggle to do good in a context of pervasive evil.

A number of books refer to a character’s Gethsemane or Golgotha experience and many use other scriptural words or themes. One character in In the Electric Mist With Confederate Dead (1993) admits: “I used to look through a glass darkly. Primarily because there was Jim Beam in it most of the time.” Or from Last Car to Elysian Fields (2003): “Was I my brother’s keeper, particularly if my ‘brother’ was a dirtbag?” The reference may be simple, but it is always apt.

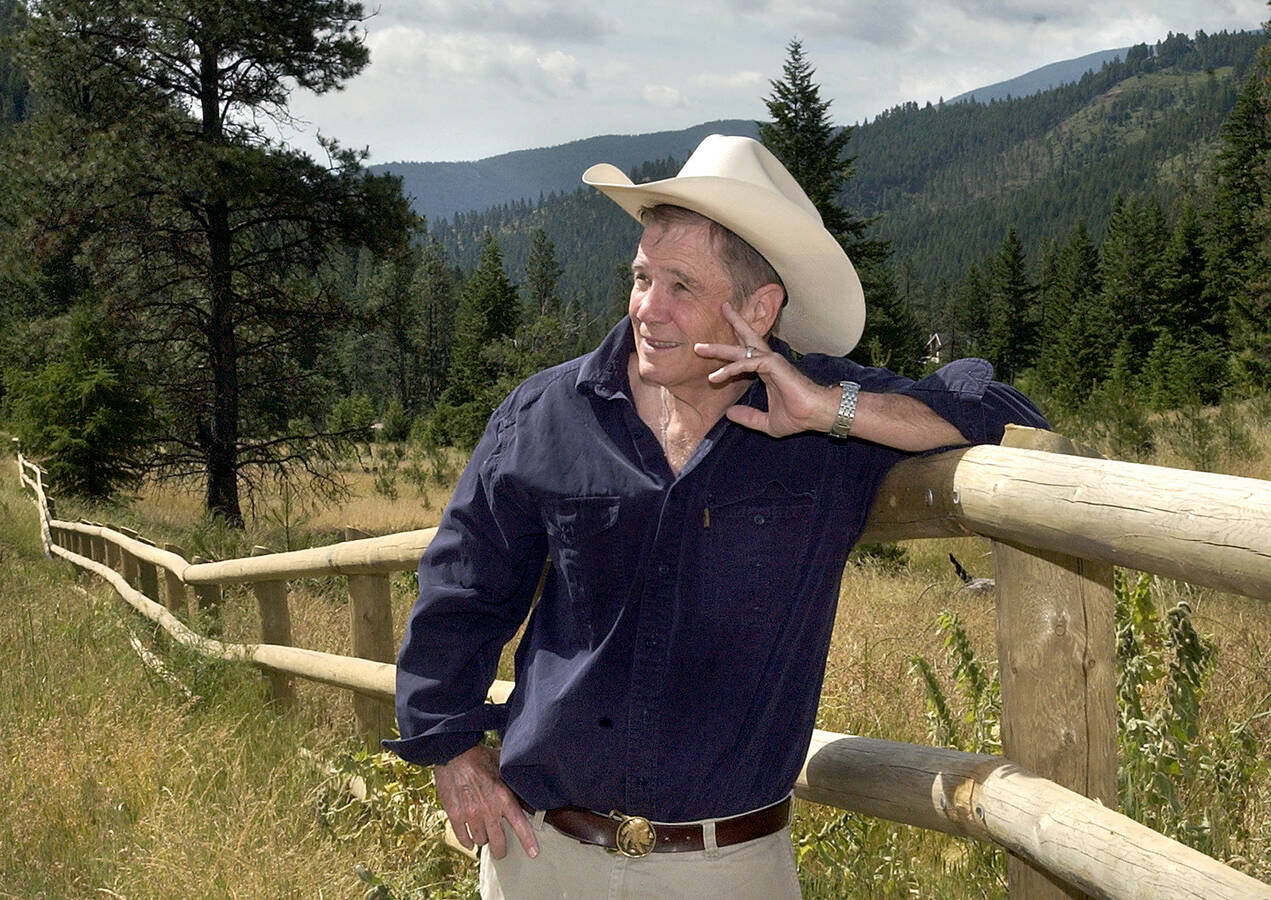

Burke’s characters are complex. His lead character in 22 novels, Dave Robicheaux—sometimes a law officer, sometimes a private investigator—is a man with a strong drive to put the bad guys away. But with his pained memories of service in Vietnam and his struggles with alcohol, he does not hide his flaws and mistakes as he tries to do good. His Catholic background and education are noted, as is his regular attendance at Sunday Mass. The really bad guys he confronts hurt him and some of those he loves (two of his wives are murdered in the novels). In the first Robicheaux novel, he is on the police force in New Orleans, but in subsequent books he moves out to the bayous around New Iberia and runs a fishing business while also working for the local sheriff. Still later he moves to Montana, and the mountains become a new setting for the violence and the detective work. Then we return to the bayous and shady streets of New Orleans.

Though his first wife runs off with a Houston oilman, later wives show him great love and support him in his drive to do good. His adopted daughter, Alafair, evokes his undying love and returns it to him. His old buddy Clete is a constant partner in fighting crime, though hardly a model for sanctity with his drinking and his womanizing. The pluses and the minuses are a constant, and the balance is a very real picture of human life.

Burke’s lead character in 22 novels, Dave Robicheaux, is a man with a strong drive to put the bad guys away.

Some of the truly evil people in the novels include drug kingpins and others in organized crime. At one point, listening to a rape victim tell her story, Robicheaux expresses great contempt for “cops and judges and prosecutors who sided with a rapist, and I’ve known many of them. There is no lower individual on earth than a person who is sworn to serve but who deliberately aids a molester and condemns the victim to a lifetime of resentment and self-mortification.” In Jolie Blon’s Bounce (2002), Robicheaux comments: “I had a recent encounter with this man. I think he’s evil. I don’t mean bad. I mean evil, in the strictest theological sense.”

In Electric Mist, an F.B.I. agent remarks to Robicheaux: “You’re always hoping that even the worst of them has something of good in him.” Most characters in fact do include some elements of good, even gang members who sell drugs on the street—they often don’t seem to have much of a choice. Women in Burke’s novels are generally good, and nuns always, with one exception. Priests are basically good, though not free of their humanity.

Religion in the Air

The first Robicheaux novel is The Neon Rain (1987), in which he is a police detective in New Orleans. In the opening scene, he sees protesters rallying outside Louisiana’s notorious Angola penitentiary, where an execution is to take place. The crowd includes “priests, nuns in lay clothes, kids from L.S.U. with burning candles cupped in their hands.” Later in the novel we hear of Catholic priests in Nicaragua and of a priest killed along with local people in Guatemala, and about Catholics in Central America generally: “They’re doing some bad shit to our people. They’re killing priests and Maryknoll nuns and doing it with the M-16s and M-60 machine guns we give them.” The wars in Central America and the Maryknoll nuns reappear in future novels. Here as elsewhere, religion is not the central theme, but it is a significant part of the atmosphere.

This first novel also has classical and cultural allusions: Cassandra, Sir Walter Scott, Prometheus and Polonius, John of the Cross, A Passage to India, Shakespeare and Robert Frost, Billie Holiday, Blind Lemon Jefferson and Leadbelly, Ernest Hemingway and James Audubon. And like almost all his novels, it gives beautiful glimpses of nature, as in the opening sentence: “The evening sky was streaked with purple, the color of torn plums, and a light rain had started to fall....” All of Burke’s novels mix in such images, and they are always natural—never heavy-handed.

Toward the end of this first novel in the series, Robicheaux asks questions of motivation, of good and evil:

I was never good at complexities, usually made a mess of them when I tried to cope with them, and for that reason I was always fond of a remark that Robert Frost made when he was talking about his lifetime commitment to his art. He said the fear of God asks the question, Is my sacrifice acceptable, is it worthy, in His sight? When it’s all over and done with, does the good outweigh the bad, did I pitch the best game I could, even though it was a flawed one, right through the bottom of the ninth?

Casual theology perhaps, but charged with insight.

The religious element is quite prominent in Burke’s 2018 novel, named for the title character, Robicheaux. Partly it is found in the background, with references to Sunday Mass, a grotto with candles flickering, crucifixes and medals hung around one’s neck. But it also has more substantive religious marks. When Robicheaux’s friend Clete Purcell recalls “the people who hurt you and me when we were kids,” Robicheaux thinks to himself:

People make peace with themselves in different ways, sometimes being more generous than they should. But you don’t pull life preservers away from drowning people or deny an opiate or two to those who have taken up residence in the Garden of Gethsemane.

In a dream about his daughter Alafair in danger, he remarks “If God had a daughter, I bet he wouldn’t have let her die on a cross.” And a bit later, referring to more dreams: “I harbored emotions that no Christian should ever have.” Again, the theology is not formal. But as it rises from a very human situation of conflict, it is very insightful.

Those religious themes persist in Burke’s most recent Robicheaux novel, The New Iberia Blues (2019). The old references appear again: the Marian grotto in New Iberia, Communion wafers, medals, Sunday Mass. Larger religious issues also appear. A dead body on a crucifix floating in the bayou is an oft-repeated image. When Desmond, a local man who has gone on to make successful films, comes back to the bayou country for a new film, Robicheaux asks him why he makes movies. Desmond replies: “They allow you to place your hand inside eternity. It’s the one experience we share with the Creator. That’s what making films is about.” Robicheaux reflects: “I was sure at that moment that Desmond Cormier lived in a place few of us would have the courage—or perhaps the temerity—to enter.”

‘You don’t pull life preservers away from drowning people or deny an opiate or two to those who have taken up residence in the Garden of Gethsemane.’

Speaking of the conflicted life of a police officer, Robicheaux reflects: “There are uncomfortable moments for almost all cops. The struggles are similar to those of the mystic with doubt about God’s existence.” The officer is fighting for what is good, but this fight stirs up contrary emotions. The officer sees too much.

At the end, when the guilty have been caught, Robicheaux takes a vacation with his daughter and his friend Clete. Reflecting on Desmond the filmmaker and his obsession with light and shadow, he remarks, “I cannot watch the sun course through the heavens and settle into a molten ball without feeling a weakness in my heart, as though God does slay Himself with every leaf that flies and that indeed there is no greater theft than that of time.”

Sin and Redemption

Burke’s theological reflections also address the everyday tensions between sincere belief and right desires that are buffeted by harsh realities and human weakness. For example, in The Tin Roof Blowdown (2007), Robicheaux reflects on his reaction to Ronald Bledsoe, an evil opponent he wishes he could kill:

Supposedly we are a Christian society, or at least one founded by Christians. According to our self-manufactured mythos, we revere Jesus and Mother Teresa and Saint Francis of Assisi. But I think the truth is otherwise. When we feel collectively threatened, or when we are collectively injured, we want the Earp brothers and Doc Holliday on the job and we want the bad guys smoked, dried, fried, and plowed under with bulldozers.

Later in the book he comments on this man: “My own belief is that people like Bledsoe pose theological questions to us that psychologists cannot answer.” In Pegasus Descending (2006), reflecting on the human condition in general, Robicheaux notes: “When people seek vengeance, they dig up every biblical platitude imaginable to rationalize their behavior, but their motivations are invariably selfish. More important, they have no regard for the damage and pain they often cause the innocent.” Earlier in that book, Robicheaux, as the narrator, describes the character Bellerophon, terrified of hell and of his own libidinous nature; for him, “God was an abstraction, but the devil was real.”

For one character, 'God was an abstraction, but the devil was real.’

More theology shows up in Swan Peak (2008). In one scene, trying to warn a woman about some danger, Robicheaux says, “In her eyes I could see the lights of shame and denial and self-resentment, and I tried to remember Saint Augustine’s admonition that we should not use the truth to injure.” And later:

Years ago, in a midwestern city whose collective ethos was heavily influenced by the humanitarian culture of abolitionists and of Mennonites, I attended twelve-step meetings with some of the best people I ever knew. Most of them were teachers and clerics and blue-collar workers in the aircraft industry. They were drunks, like me, but by and large their sins were the theological equivalent of 3.2 [percent] beer.

He comments too on the nature of God. In Crusader’s Cross (2005), he speaks of his father “big Aldous, [who] spoke a form of English that was hardly a language.… But when he spoke French he could translate his ideas in ways that were quite elevated.” Aldous, he comments, used to say, “There are only two things you have to remember about Him: He has a sense of humor, and because He’s a gentleman He always keeps His word.”

Several characters in Burke’s books are former Jesuits, and one murder victim is a Jesuit. Jesuit names appear in places in Montana: Cataldo, Ravalli, St. Regis. And casual references are made to Loyola University in New Orleans and the Grand Coteau retreat house. Early in one interchange with a federal agent in The Neon Rain, the agent tells Robicheaux: “I get a little emotional on certain subjects. You’ll have to excuse me. I went to Jesuit schools. They always taught us to be upfront about everything. They’re the Catholic equivalent of the jarheads [Marines], you know.” And in a later conversation, “Don’t try to tilt with a Jesuit product, Lieutenant. We’ve been verbally demolishing you guys for centuries.”

So what about the “theology” label? In Swan Peak, Robicheaux says “I am not a theologian.” And in Pegasus Descending, he responds to his wife Molly’s question, “You don’t think God can understand that?” with the comment: “I am not a theologian, but I believe absolution can be granted to us in many forms. Perhaps it can come in the ends of a woman’s fingers on your skin. Some people call it the redemptive power of love. Anyway, why argue with it when it comes your way?” On a related note, in Swan Peak, Molly says to Robicheaux: “Under it all, you’re a priest, Dave.”

Along with cultural and historical references and amazing glimpses of nature, the religious and the theological surface to do their work and then give way, adding their essential flavors to the whole. Perhaps it is enough to say James Lee Burke is a great writer. No other labels are needed.

He also set a novel in West Virginia, and in it explored sexual abuse and what happens when one's own family harbors great evil. He is a great writer, one whose long descriptions are as readable as the lively action and dialogue.and his metaphors hit hard. As a person raised in New York, and Jesuit educated, I was happy to find a great writer who so skillfully explored the US underclass, including the rural. I liked that his novels were not set in universities or in professional offices. I was raised in a relatively poor family in a relatively poor neighborhood but families were intact and on the whole loving and even wise. And the cops on the whole were OK (and personally known to the parents). But we were well educated in grade school and high school on the shameful aspects of US history. It was refreshing to read a brilliant author who managed to make great literature out of the disturbing realities of life in the USA. As a writing stylist I admire him greatly along with Lee Child (The Reacher books that also well explore obscure and disturbing realities in the USA).

My favorite fiction author by far. I’m from south Louisiana and he is authentic in his descriptions of the culture, the environment, and the crisis in faith when confronting evil. His depth and his way of describing nature are always astounding.