Back in January, the Rev. Gary Graf, a Catholic priest at St. Procopius Parish in Chicago, made an unusual announcement during Sunday Mass. As President Trump battled Democratic congressional leaders over immigration, Father Graf said that he was embarking on a hunger strike until the fate of the so-called Dreamers—undocumented immigrants brought to the United States as children—was resolved.

“Yes, it’s dramatic,” Father Graf told The Chicago Tribune. “It’s a way in which we pray for our political leaders and invite them to do their jobs.”

During the past year, from Chicago to Ankara, from Georgetown to the Middle East, hunger strikes have been a surprisingly popular strategy for activists and prisoners. In January two Turkish educators who lost their jobs in the wake of the failed coup against President Recep Tayyip Erdogan ended an 11-month hunger strike, after each had lost more than 40 percent of his body weight. That same month, a Jordanian-born businessman from Youngstown, Ohio, and a Mexican-born Army veteran from Chicago also announced they were going on hunger strike after they were targeted for deportation by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Hunger strikes raise thorny political, philosophical and even spiritual questions.

Last May hunger-striking Palestinian prisoners were joined by Patriarch Gregory III Laham, the 84-year-old former primate of the Greek-Melkite Catholic Church, protesting what they termed inhumane conditions in Israeli prisons. Inmates at California’s Folsom State Prison cited similar concerns when they initiated their own hunger strike in 2017. Finally, students, faculty members and alumni at a number of Catholic universities—including Georgetown, John Carroll and Notre Dame—engaged in hunger strikes to call attention to what they characterized as inhumane treatment of farm workers.

Last year and this year also mark the 100th anniversary of a series of lengthy hunger strikes declared in the name of women’s rights, pacifism and anti-colonialism—one of which even produced a candidate for sainthood (more on that later). Hunger strikes, of course, spring from a desperate desire for justice. But they also raise thorny political, philosophical and even spiritual questions. How should we react to a hunger strike—especially once the striker begins to suffer? And, theologically speaking, is a hunger strike akin to a suicidal—and, thus, sinful—act?

This question is particularly relevant in Ireland, which celebrates the 20th anniversary of its fragile but still holding Good Friday peace agreements in April. Hunger strikes remained an effective tactic for Irish Catholic activists throughout the 20th century, even as theologians and politicians debated their morality. It is not difficult to find websites or forums that claim (as catholicdoors.com puts it) that “to commit suicide through a hunger strike is a mortal sin that leads to eternal damnation.” Many historians and theologians, however, take a much more nuanced view.

The writer and historian Peter Quinn calls them “a legitimate tool of the powerless against the powerful.”

The writer and historian Peter Quinn calls them “a legitimate tool of the powerless against the powerful.” Mr. Quinn went to Northern Ireland at the height of the hunger strikes controversy there in the early 1980s, when he was working for Hugh Carey, then governor of New York. Hunger strikes, Mr. Quinn adds, “reassert the power of the prisoner over his own person and simultaneously challenge the captor to use his power to end the strike or prolong it.”

Jeremy Cruz, a theology professor at St. John’s University in New York, says, “Those who make the argument that [hunger strikes] are sinful rely on the idea that suicide is an ‘intrinsic evil.’” But, he adds, the circumstances that drive a person to make a hunger strike must also be taken into account, and systemic abuse and inequality can too easily be forgotten in debates over the morality of fasting.

“The real ethical question we need to ask,” Mr. Cruz says, “is, how do we advance social justice so that people don’t feel compelled to starve themselves?”

“How do we advance social justice so that people don’t feel compelled to starve themselves?”

Historically speaking, hunger strikes have been relatively rare, at least prior to the 20th century. Historians locate the roots of hunger striking in ancient Roman, Celtic (in which it was called troscad or cealachan in Gaelic) and Indian (“sitting dharna”) cultures. They were generally used to draw unwanted attention—shame—to a person who had failed to pay a debt or broken some other valued cultural norm.

Prisoners under czarist Russian regimes in the 19th century sporadically engaged in hunger strikes. By the late 1800s, Laurence Ginnell, an Irish nationalist and member of parliament, noted that hunger striking, under ancient Irish legal codes, “was clearly designed in the interests...of the poor as against the mighty.” He added, however, that “distress by way of fasting [was] now so strange to us because so long obsolete.” And yet a decade and a half into the 20th century, hunger strikes would expose severe weaknesses in the mighty British Empire.

The modern era of hunger striking is generally considered to have begun in June 1909. Scottish-born Marion Wallace Dunlop, a member of the Women’s Social and Political Union, was arrested in England during a suffragette campaign. Once imprisoned, Ms. Dunlop refused to eat, initially dismaying even allies in the movement. But in a matter of weeks, three more suffragettes went on hunger strike. British authorities eventually decided to force-feed these women through their noses and throats, an invasive, often brutal process. Other hunger strikers were released when they became weak only to be re-arrested once they became healthy, a heavily criticized process that came to be known as “cat and mouse.” It was a pattern that would occur again and again: hunger strikers turned into aggrieved martyrs by heavy-handed authorities.

The first years of the 1910s turned out to be a crucial turning point in the history of hunger striking. The tactic—and the accompanying very public, very political suffering—spread across the globe.

In 1913 a 44-year-old Indian activist named Mohandas Gandhi began the first of his many fasts.

In 1913 a 44-year-old Indian activist named Mohandas Gandhi began the first of his many fasts, this one to protest the treatment of Indians living in South Africa. Gandhi would become synonymous with hunger striking right up until his assassination in 1948. In 1929, the activist Jatin Das died while on hunger strike in a Lahore prison, protesting British treatment of Indian political prisoners.

But it was in another beleaguered British colony—Ireland—where the hunger strike was most widely employed, even before the Easter rebellion against British rule in 1916. Irish hunger strikes were employed during a massive 1913 labor dispute and to oppose British efforts to recruit Irish soldiers for World War I. By Easter 1916, when the British crushed a rebel uprising, hunger strikes were woven into the fabric of Irish activism. In 1917, dozens of Irish prisoners went on hunger strike, including Thomas Ashe, who died after being forcibly fed.

As hunger striking became central to the Irish struggle, theological debates followed. Writing in The Irish Ecclesiastical Record, the Catholic chaplain at Dublin’s Mountjoy Jail, John Waters, said, “Though I could never see any reason to doubt that the hunger strike was suicide, I am bound to say that I had but very little success in inducing the strikers to adopt my views.”

Following the 1920 death of the lord mayor of Cork, Terence Mac Swiney, after a 74-day hunger strike, the Jesuit theologian P. J. Gannon actually defended the tactic, writing: “No hungerstriker aims at death.... His object is to bring the pressure of public opinion to bear upon an unjust aggressor.... There is nothing here of the mentality of suicide.”

The decades that followed saw dissidents across the globe die during hunger strikes: Pedro Luis Boitel in Cuba, Emil Calmanovici in Romania, Anatoly Marchenko in the Soviet Union, Potti Sreeramulu in India.

Meanwhile, 2017 marked a century since the United States entered World War I, with a great burst of patriotic fanfare. Much less celebrated has been the pacifist movement that opposed U.S. involvement in the Great War. One of the most high-profile resisters was Ben Salmon, a devout Catholic who embarked on a hunger strike that lasted 135 days. The Denver Post labelled him a “man with a yellow streak down his spine as broad as a country highway.” Today, however, Catholic activists are building a case to canonize Salmon.

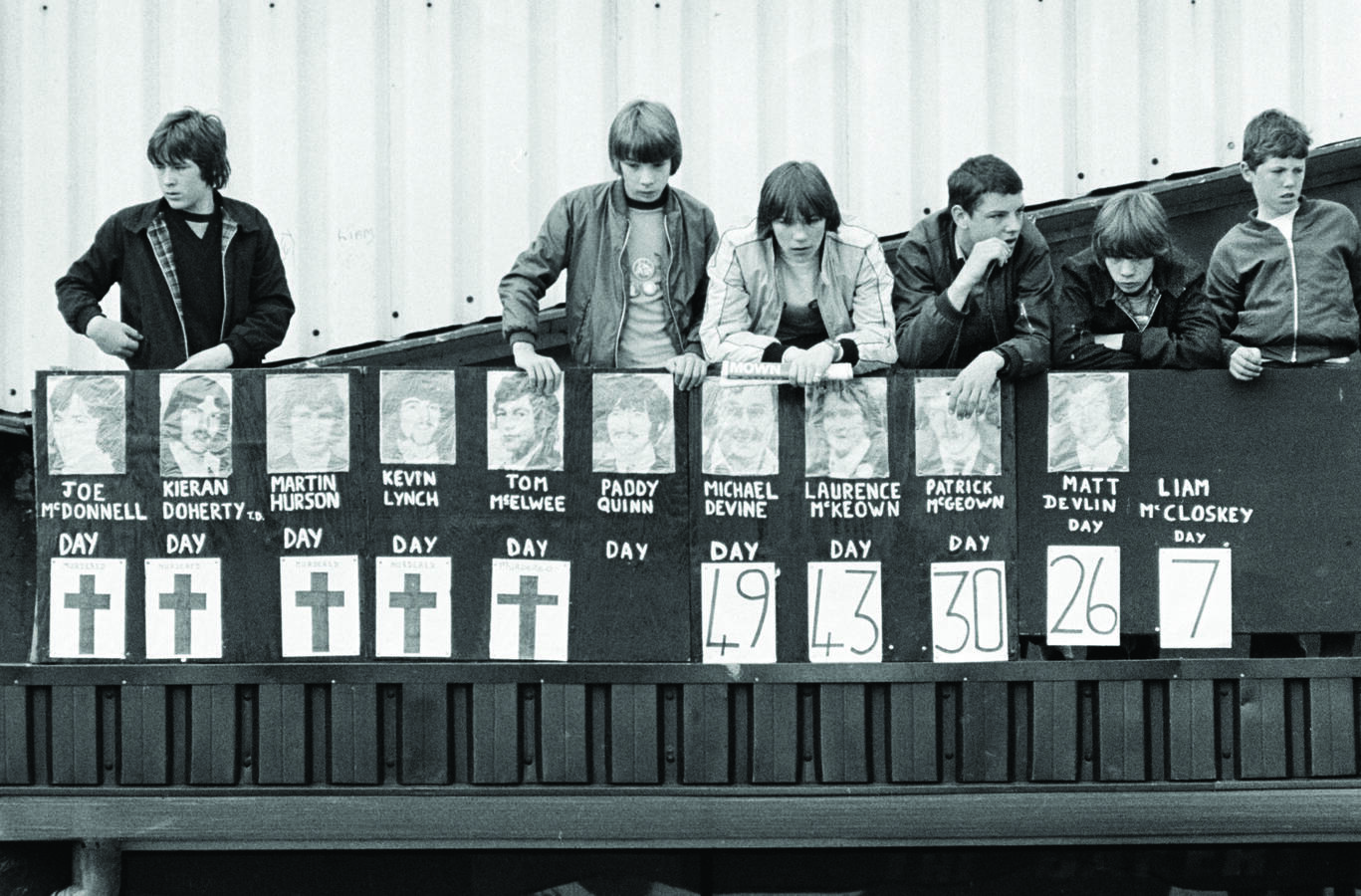

More recently, hunger strikes came to be inextricably linked with the Catholic civil rights movement in Northern Ireland. Beginning with the death of hunger striker Bobby Sands on May 5, 1981—a month after he had been elected a member of Parliament—the eyes of the world watched the showdown between hunger strikers and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher of Britain.

More recently, hunger strikes came to be inextricably linked with the Catholic civil rights movement in Northern Ireland.

“Mr. Sands was a convicted criminal. He chose to take his own life. It was a choice that his organization did not allow to many of its victims,” said Ms. Thatcher, refusing to give in to various prisoners’ demands. By late August, 10 Irish Republicans were dead and a fierce global debate—were Bobby Sands and his comrades martyrs or fanatics?—commenced.

Looking back on this heated time in 2016, The Irish Times ran an article entitled “Suicide or Self Sacrifice: Catholics Debate Hunger Strikes.” Maria Power, a lecturer in religion and peace-building at the Institute of Irish Studies, University of Liverpool, wrote, “The events and debates surrounding the hunger strikes shone a blinding spotlight on the hierarchies of the Irish, and English and Welsh Catholic Churches.”

Archbishop John R. Roach, then president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, referred to Sands’s death at the time as “a useless sacrifice.” But others argued that the hunger strikers could be absolved if they believed in their “individual conscience” that they were trying to right larger wrongs. Maria Power told America this split had national, class and even ideological roots.

“The main debate was occurring between English and Irish Catholics,” noted Ms. Power. “To the English, the hunger strikes were sinful because those engaged meant to fast to the death. But to Irish Catholics, the hunger strikers…[were using] their bodies as a weapon to get the British government to acquiesce.”

Father Brian Jordan, a Franciscan, was a student at Washington Theological Union during the Irish Hunger Strikes. They “were omnipresent in my mind, heart and soul,” he told America. “I am both pro-life and pro-social justice. I contend the hunger strikers believed they were acting in a just manner against an unjust aggressor.”

The novelist Mary Gordon clearly had the Irish legacy of hunger striking in mind when she wrote her disturbing novel Pearl in 2004, about an American student who goes to Dublin to study linguistics only to chain herself to a flagpole and refuse to eat. Lurking under the surface of Ms. Gordon’s novel are many unsettling questions—among them: Why would an upper-class, once-apolitical American turn to a tactic generally reserved for only the most desperate and oppressed? And: Is it possible that some people do not have a moral right to resort to hunger striking?

The flurry of recent hunger striking has led to similar questions. When parents and activists went on hunger strike to protest the closing of a Chicago high school in 2016, Eric Zorn wrote in The Chicago Tribune: “When a hunger striker truly believes that he or she would rather die than continue to live under current conditions...then, yes, their plight, their claims deserve extra attention and expedited handling.”

Hunger striking graduate students at Yale also came under fire because they had talked about replacing hunger strikers who become weak or ill. Amy Hungerford, a professor and dean at Yale, wrote in The Chronicle of Higher Education, “A hunger strike...implies a false equivalence between these students at Yale and the millions on whose behalf Mohandas K. Gandhi, César E. Chávez, and others sacrificed their bodies to hunger.”

Hunger strikes, of course, should never become a fad. But it is also clear that the 20th-century activists Ms. Hungerford cites continue to inspire. At a time of massive inequality (not to mention deep historical ignorance), this is a victory in and of itself—even when a conflict seems decidedly a first-world issue like, say, choosing between a taxicab or an app-based transportation service.

“[W]hat is left for us?” one hunger-striking cab driver asked in December 2015, during a dispute between Toronto’s cabbies and the ride-hailing service Uber. “You want to kill my industry? Kill me first. Let me starve over here.”

This may seem a touch un-Gandhian, but that does not make this cab driver’s plight any less desperate. Gandhi himself might well have recognized that.

Lead image above: Pictures of Irish hunger strikers interned at Maze prison hang from a balcony in West Belfast, Aug. 9. 1981. Ten Catholic hunger strikers died at Maze in 1981, including Bobby Sands, who had been elected a member of Parliament.