Review: Phyllis Zagano makes the case for women deacons

“You’re a theologian,” my priest said to me in his old-world Irish brogue. He pulled an article out from a drawer and plopped it between us on his desk. I had come to talk about my upcoming wedding, but we were also chatting about my questions about salvation and the Second Vatican Council. I had no idea what a theologian was or what he wanted to show me.

After the conversation, he asked me to join the team that led our parish’s conversations for the Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults, and he gave me the article. It was an essay by Phyllis Zagano.

For the past 25 years, Zagano has shaped the discourse on gender and the history of leadership in the Roman Catholic Church with multiple award-winning articles and books. In particular, she is one of the world’s foremost experts on the history of the diaconate. She has written on how the meaning of this role has shifted over the last two millennia. More provocatively, she has written about who has filled this role in different circumstances and times in church history. Zagano’s thorough historical scholarship has shown that we must count women in that number.

Phyllis Zagano has written about deacons in different circumstances and times in church history. Her thorough historical scholarship has shown that we must count women in that number.

While Zagano thoughtfully draws out the theological implications of her research, her main point is historical: There is simply no precedent on which to base the exclusion of women from the diaconate in the Catholic Church. Further, Zagano argues that there can be an ordination of women to the diaconate without any implication that women could be ordained to the priesthood. The formal sacramental ordination of a person into the diaconate and priesthood are different enough in kind that the ordination of women deacons does not imply the possibility of the ordination of women priests.

The question of women in the diaconate became relevant after Vatican II, when a permanent diaconate was established for the first time in centuries. Between the councils of Trent and Vatican II, there was no permanent diaconate in the Roman Catholic Church. The order of deacon was instead part of Holy Orders (one of the seven formally proclaimed sacraments), which has three levels: deacon, priest and bishop. In this understanding, all deacons were priests-to-be.

Could there be a place for women in the permanent diaconate?

After Vatican II, the permanent diaconate, modeled on a role found in the early church, was reinstituted. Today deacons are ordained; they must be over 35; and they can be married. Deacons can baptize, witness marriages, perform funerals and burial services outside of Mass, distribute holy Communion, proclaim the Gospel and preach the homily. Married deacons, who wear a stole diagonally across the chest rather than in parallel lines, are a familiar sight in many U.S. parishes. A deacon cannot, however, administer the sacrament of confirmation, hear confessions, anoint the sick or consecrate the eucharistic gifts.

Could there be a place for women in the permanent diaconate?

Zagano has addressed this question throughout her career, arguing for a single sacramental permanent diaconate for men and women. Her latest book, Women: Icons of Christ, provides an excellent and accessible summation of her research for a lay audience. Each chapter examines ways women have participated and been acknowledged as deacons in the body of Christ. These include: baptism, catechesis and preaching, altar service, spiritual direction, and anointing and healing. Zagano’s copious research allows her to explore examples throughout history.

The only person in Scripture called “deacon” is named in Paul’s Letter to the Romans, where he addresses the deacon—the woman deacon—Phoebe.

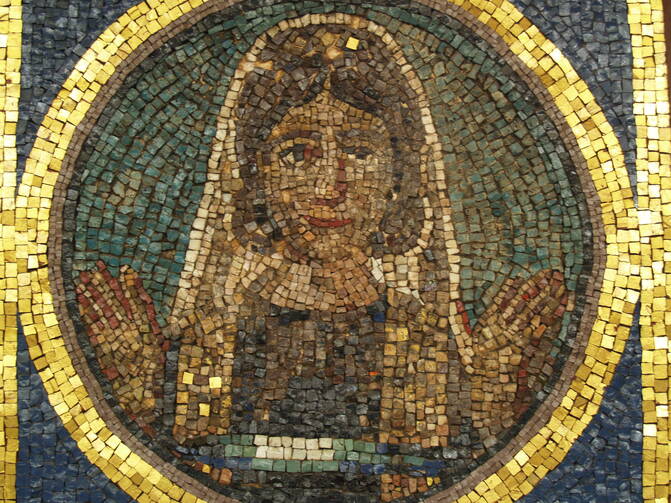

The most famous example of a woman deacon comes from Scripture. In fact, the only person in Scripture called “deacon” is named in Paul’s Letter to the Romans, where he addresses the deacon—the woman deacon—Phoebe. And in the sixth century, the German princess Radegund, for whom many churches in Western Europe are named, was consecrated with laying on of hands as a deacon. Around this same time, many women performed sacred tasks such as baptizing and anointing for other women precisely because it was seen as improper for a man to touch or see women in this context.

Zagano shows that it was the medieval church that put explicit strictures on the sacramental acknowledgment of women’s ministries. This was done by using notions of uncleanliness and misogyny that most priests today would find abhorrent on their face. Today, of course, Catholic women perform many ministerial tasks, such as spiritual direction, hospital chaplaincy, roles on parish councils and catechesis. Zagano shows that this kind of participation is not new and that it was recognized as sacramental from the early church until late in the first millennium of the church’s existence.

The context in which this book is published is of particular note. In 2016, Zagano was appointed by Pope Francis to a 12-person study commission on the women’s diaconate. The goal of this study was not to advise the pope on what to do going forward, but to provide reliable information about the history and theology of the early church on the status of women in the diaconate and then for the pope to discern the issue himself. Zagano recounted her experience in an interview with America last year. That commission was disbanded in 2018, with Pope Francis noting the group was divided on what conclusions to draw.

A new 10-member commission was announced on April 8. The purpose of this commission is similar; but unlike its predecessor, it is also explicitly tasked with making recommendations. Jamie Manson of The National Catholic Reporter has written that a number of members on the new commission are ideologically aligned against the movement toward a women’s diaconate. None of the previous members are on the current commission, and it seems a real loss not to have Zagano’s specific expertise available there.

The medieval church put explicit strictures on the sacramental acknowledgment of women’s ministries. This was done by using notions of uncleanliness and misogyny that most priests today would find abhorrent on their face.

This new book describes the fruits of Zagano’s many labors, both before the 2016 commission and during it. Women: Icons of Christ is not only informative; it may also be a helpful guide for discerning the nature and purpose of recommendations that may be made by the new commission.

Zagano informs us that one theory of the etymology of the word diakonia is “that it comes from the meaning ‘through the dust’ [and that] the deacon ministers, serves, and brings the message, literally, ‘through the dust’ of the world and its afflictions. As icons of Christ, ordained women deacons served thusly.”

Zagano’s call is not just practical and historically grounded. It is a prophetic call to recognize women’s participation in the body of Christ, a call that not only denounces harm to women but to the church that deserves our gifts.

A year after that first conversation with my priest, I began work toward a master’s degree in theology. I am not a deacon. But I am grateful to Zagano for showing me what kind of place women have had and can have in the church, both through her research and her powerful example as a theologian. I recommend Women: Icons of Christ to any person who wants to learn more about the history and importance of women in the Roman Catholic tradition and to women who want to reflect on their own value in it today.

Correction, April 28, 2020: Due to editing errors, a previous version of this article incorrectly described the rite of ordination to the diaconate as an anointing, and described a deacon's stole as a sash.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “A woman’s place is in the church,” in the May 11, 2020, issue.