Kazuo Ishiguro’s ‘Klara and the Sun’ is a haunting tale of love, loss and...a robot.

When I was a senior in high school, I decided on a whim to pick up Kazuo Ishiguro’s science fiction masterpiece Never Let Me Go. At the time, I had no idea what utter misery was waiting for me in Kathy, Tommy and Ruth’s boarding school adventures—nor could I have predicted the many months Never Let Me Go would spend in my mind after I finished reading it.

That first encounter with Ishiguro’s writing cemented his place as one of my favorite authors. Now I find myself gravitating toward his titles whenever I can browse in libraries or bookstores, eagerly losing myself in his engrossing stories and lovely prose. Still, nothing quite haunted me as relentlessly as Never Let Me Go did—until I picked up Klara and the Sun.

In March, Ishiguro released Klara and the Sun, his eighth novel and first literary work since winning the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2017. Klara and the Sun also represents the first return to science fiction for the acclaimed author since Never Let Me Go in 2005. The book not only lives up to its predecessor’s legacy, but in some respects surpasses it.

The novel is set in a dystopian United States encumbered by surging social inequality, fascist terrorism and controversial scientific advancements. In this bleak future, parents may “opt in” their children for a risky genetic modification treatment called “lifting” that boosts their social standing and academic prospects. “Lifted” children follow a strict home education and socialization regimen. “Unlifted” children are ostracized by their peers, essentially left to their own devices.

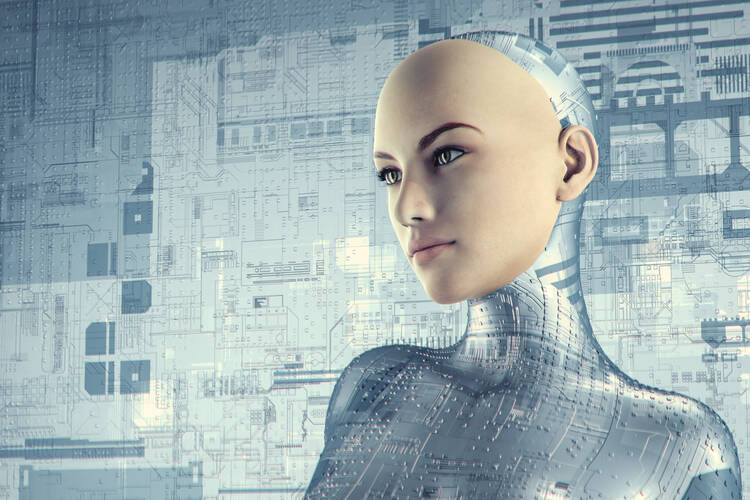

The robotic narrator of Kazuo Ishiguro's new novel takes us into a dystopian U.S. future.

In addition to the “lifting” process, the society of Klara and the Sun also features highly advanced artificial intelligence so sophisticated in its programming that its mere existence blurs the boundary between human and machine. The anxiety this causes is exacerbated by the gradual elimination of the country’s white-collar workforce. The artificial intelligence functions so effectively and accurately that it ultimately proves more desirable than human efforts—at least where the economy is concerned. Even companionship and intimacy are no longer exclusive to living persons, as toy companies manufacture Artificial Friends (AFs), solar-powered robotic dolls with exceptional learning capabilities who accompany lonely children throughout their adolescence.

We experience this precarious world through the perspective of Klara, a remarkably observant, inquisitive AF who is fascinated by human behavior. Unlike other AFs, who simply wish to be paired with a human child, Klara yearns to understand the subtleties and nuances she detects in people’s interactions with one another. From her position in the toy store’s display window, our attentive narrator loves nothing more than to watch people pass by and imagine what is going on in their heads.

One day, Klara is sold to a kindhearted 14-year-old girl named Josie. Klara’s world grows significantly more complicated. She learns that Josie is dying from a serious illness; suddenly, Klara’s purpose changes. Her objective no longer involves looking after a developing child. Instead, Klara must comfort a girl resigned to die.

Klara and the Sun is set in a dystopian United States encumbered by surging social inequality, fascist terrorism and controversial scientific advancements.

What follows is a deeply moving story about love, sacrifice and faith as Klara learns to grapple with the anticipatory grief of losing a loved one. Ishiguro strikes a tender, affecting tone, inviting us to dwell in the darkness that can envelop someone approaching death. We experience the characters’ suffering, their pain and desolation, their resentment and resignation, their quiet hope, their desperate longing for a miracle. Josie’s ordeal is devastating and—for many of us—achingly familiar.

There is a lot to admire in Ishiguro’s new book, from its premise and execution to its pathos and thought-provoking themes. The novel’s crowning achievement, however, is Klara’s narration.

Ishiguro is a master of first-person storytelling in modern literature. His narratives are known for pulling readers directly into a character’s consciousness, for obscuring his authorial presence and for giving narrators complete control over their story’s unraveling. His writing excels not only in capturing a character’s authentic voice, but in using that voice to propel the narrative forward. Ishiguro’s narrators rarely deal in exposition or try to hold the reader’s hand. Rather, it is up to the reader to pay close attention to the important details hidden in characters’ passing comments, and to notice the narrator’s purposeful omissions in order to see the story’s bigger picture. The result is prose that feels both beautifully natural and intellectually stimulating.

Kazuo Ishiguro is a master of first-person storytelling in modern literature.

Klara and the Sun maintains the same transcendent narrative quality one would expect from Ishiguro. Klara’s perspective is one of an almost childlike naïveté about the world around her. At the same time, her narration straddles the line between personable and algorithmic, allowing readers to interpret how much of Klara’s worldview is informed by her programming.

What is truly brilliant about Klara is that she operates as an unreliable narrator despite her unflinching honesty. She does not conceal her observations or motivations from us, and though her “duty to assist Josie” is an innate part of her digital makeup, Klara does seem to exhibit true affection for the girl. Still, we cannot ignore the reality that Klara is not human. She can observe, but she cannot fully comprehend the human heart; her algorithm is too limited. Klara’s storytelling may be factually accurate, but is it emotionally true?

A perfect example of the narrator’s limitations can be found early on in the novel, when Klara witnesses a fistfight between two taxi drivers outside the toy store. While she can successfully identify the men’s emotions based on their facial expressions and body language, Klara realizes she cannot feel empathy for them. In fact, empathy is such a foreign concept for her that she deprecates it as a ridiculous notion: “I tried to find the beginnings of such a feeling in my own mind. It was useless though, and I’d always end up laughing at my own thoughts.” (This inability to empathize takes a more sinister turn later, but I would not dare spoil the novel’s bombshell twist.)

Despite Klara’s limited perspective, Ishiguro ingeniously uses her distinctly un-human character to illuminate universal human experiences. Klara allows us to see ourselves more clearly, to be reminded of the “special something” that makes us human. We are not replaceable. We do not belong solely to ourselves. Ultimately, we are created, nourished and shaped by love.

More from America:

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “Learning love from a robot,” in the June 2021, issue.