Review: What Marshall McLuhan can teach us in the age of digital media

Nick Ripatrazone’s new book on Marshall McLuhan, Digital Communion, arrived in my mailbox the day I presented a play about Marshall McLuhan at a conference on the Catholic imagination in Dallas, Tex. A fitting coincidence, if such things exist.

I began writing the play as part of the Church Communications Ecology program at the McGrath Institute for Church Life at the University of Notre Dame. The program brought together around 30 communications professionals to read, learn and create projects to help the church communicate its message in a digital age. “Communications professionals” was a broadly defined term. Our cohort consisted of college professors, high school teachers, writers, digital media entrepreneurs, seminarians and two artists (myself one of them).

We met via Zoom for two months at the beginning of 2022 to discuss a wide range of readings. We read theology from Bonaventure and Romano Guardini, as well as from ecological thinkers like Rachel Carson. We pondered Andy Warhol’s imagination and learned the communication theory behind Fred Rogers’s television neighborhood. We watched Bo Burnham’s “Inside,” discussed the phenomenon of Wordle on our class message boards and consumed media theorists Walter Ong, S.J., and Marshall McLuhan.

In the 1960s, McLuhan already saw the internet on the horizon when the rest of the world was falling in love with broadcast television.

Nick Ripatrazone, author of Digital Communion,visited one of these Zoom classes. In our class, he spoke about his new book and shared its thesis: “McLuhan’s Catholicism is not a footnote but rather a foundation of his media theories.” For a thinker like McLuhan, who is not as widely celebrated as other 20th-century American Catholic thinkers, this simple thesis is a surprisingly radical new paradigm.

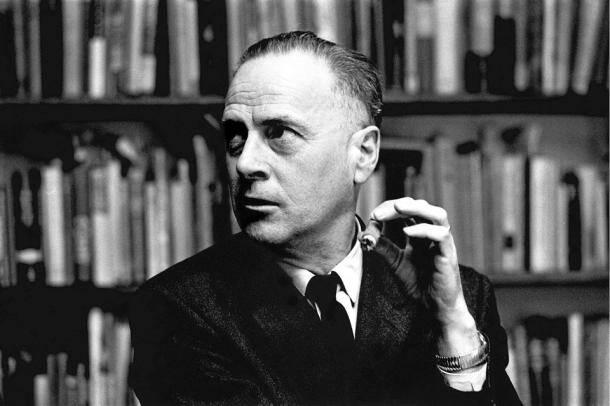

Born in Alberta, Canada, in 1911, McLuhan converted to Catholicism in 1937 while at Cambridge writing his dissertation. He became a professor at St. Michael’s College in Toronto, and his first books, The Mechanical Bride (1951) and The Gutenberg Galaxy (1962)skyrocketed him to public intellectual fame in the television age.

Ripatrazone’s Digital Communion opens with a pericope describing the first televised papal Mass in the United States—in Yankee Stadium on Oct. 4, 1965—a story that introduces the dramatic tensions between technology and faith. And perhaps a story that shows the Catholic Church is unprepared, as it was with the advent of the printing press, for the seismic shifts a new medium like television will cause.

After this opening anecdote, the book cuts to McLuhan’s appointment to the Pontifical Council for Social Communications. McLuhan, Ripatrazone argues in multiple chapters, was perhaps ahead of his time. In the 1960s, McLuhan already saw the internet on the horizon when the rest of the world was falling in love with broadcast television. Now that we are streaming television shows in the palm of our hand around the clock, we are ready for McLuhan’s prophecies of the digital age.

Ripatrazone’s style in this spiritual biography and light theological exegesis of McLuhan’s thought echoes McLuhan’s own mosaic style. The author fills the pages with McLuhan’s own words, which is easy to do since McLuhan is an infectious coiner of aphorisms. McLuhan’s idiosyncratic formulations are always striking and original, making it difficult to resist quoting him verbatim.

Ripatrazone dives into McLuhan’s singularly personal life, phraseology and his core beliefs, excavating the Catholic thread running through each. He tells the story of McLuhan’s conversion at Cambridge. McLuhan’s love of Gerard Manley Hopkins and James Joyce led him to Catholicism and inspired his media theory. Ripatrazone also delves into McLuhan’s skepticism of Gutenberg and his printing press, the shrinking and uniting effects of print and digital media and the concept of the global village.

Print itself is a more mechanical intervention than perhaps we digital natives realize. We are so used to virtual environments that communication outside of screens seems more natural and organic. But, McLuhan notes, Gutenberg’s printing press was the first media invention to make the world small.

Print itself is a more mechanical intervention than perhaps we digital natives realize. But, McLuhan notes, Gutenberg’s printing press was the first media invention to make the world small.

Gutenberg’s print alphabet, McLuhan believed, contributed to the Reformation. The repeated type, printed over and over again, with no individuality, more quickly produced than a manuscript, creates an industrialization of knowledge and an individualized access to it. It divides the world into small, accessible corners. McLuhan sees print as an individualizing and fragmentary medium. And the digital world, for McLuhan, brings us back into communion.

Which brings us to the concept of the global village, the situation we find ourselves in today. We find communion made difficult, ironically, by the hyper-connectivity of the internet. We are too wildly plugged into “a little bit of everything all of the time,” as Bo Burnham describes the internet. Patricia Lockwood dubs the World Wide Web: “The portal you enter only when you needed to be everywhere.” And if you are everywhere, you are, of course, nowhere.

We cannot escape our environment—we live in a particular climate zone, in a particular state, in a particular city, in a particular neighborhood. And digital media is part of that environment—the global village crashing into our city street.

But we can choose to engage with questions of how we will engage with our environment: What kind of global villager will we be? What sort of neighbor? How will we care for the world around us? How can we interact with the devices that are our media in our own terms, not in the terms they set, which, as McLuhan says, turn us into “servo-mechanisms.”

Many artists and other malcontents (like myself) who pick up on the poison in our environment see the content or individual technologies as the villains. McLuhan has reminded me, as Ripatrazone does, that the effort of digital communion and liturgy in the digital age is not so much a fault of an iPhone or a Zoom screen or a camera observing Mass, but it is environmental. The digital world creates an environment that forms us into habits of being: inattention, distraction, scrolling. But we can resist those environmental habits and reactions.

In fact, perhaps it is the task of the artist, McLuhan suggests, to draw attention to our environment, to the ground of our being-together, and the habits it forms. “The present is always invisible because it’s environmental and saturates the whole field of attention so overwhelmingly,” wrote McLuhan, “thus everyone but the artist, the man of integral awareness, is alive in an earlier day.” The artist, McLuhan suggests, is the member of society who clearly sees the present, not the past.

Perhaps it is the task of the artist, McLuhan suggests, to draw attention to our environment, to the ground of our being-together, and the habits it forms.

The play I presented in Dallas, “Is the Internet in Color?” tells the story of a woman with Alzheimer’s disease who befriends a young journalist. A woman who holds the past in her body finds the present slipping away from her grasp. Her memory loss means the only reality for her will soon be the memories stored in her head. Borne back ceaselessly into the past has a violently literal meaning.

With theological and poetic interjections by Michael Murphy of the Hank Center for the Catholic Intellectual Heritage at Loyola Chicago University and McLuhan-esque riffs by Brett Robinson, of the McGrath Institute for Church Life, we created a dialogue of sorts between the characters of the play and the ideas contained within the story of Nancy’s struggle with Alzheimer’s.

The woman, Nancy, meets a young man—a paradigmatic zoomer—whose journalistic job it is to record the memories of a collective body, a public. His industry is dying, as the internet is slowly killing local journalism as we once knew it. Does the internet force us to live in the past, like Nancy? Is it the preserved instantaneous, insignificant moments like having oatmeal for lunch, a latte featuring a heart made of foam, or drinks with the girls in Cabo that live forever on a timeline? Are we stuck in the past or in the present? “The present / is too much for the senses,” writes the poet Robert Frost, “too present to imagine.” Such a sentiment could also be said of the World Wide Web.

The gift of the artist, McLuhan said, is to draw a new awareness or attention to something in an environment. “The artist’s role is not to stress himself or his own point of view, but to let things sing and talk, to release the forms within them,” said McLuhan in a 1959 talk to seminarians.

The artist—at least the playwright—creates art that demands the participation of the audience. Unlike a television segment, a play is something created with the audience viewing it: their temperament, their reactions, their questions. It is a true liturgical act of participation, something the television age never quite captured.

Despite the connectivity of the digital age, we find ourselves increasingly alone. A play is one of those rare liturgies that helps us make meaning together. A play, like a print book about McLuhan, like the prophetic, pencil-wielding professor himself, is perhaps an artifact and medium of culture that can and will persist. Because it contains in itself something essential to our human nature.

How do we enflesh God in a new age, in a new environment, when our understanding of language, communication and reality has been transformed?

Nature finds a way of sneaking into our perfectly curated environments. We find friction even when the digital environment is designed to be frictionless. We grow impatient when the internet is frozen, when Facebook’s servers go down, when Instagram can’t load and when our iPhone screen gets cracked. We find our global village is not an isolated community but part of a creation, part of a cosmos.

Although McLuhan agreed with his Jesuit influences that God is in all things, including the electronic light of the internet, he also understood that a society who had fundamentally remade its media had shaken its metaphors for our mediated God. Letters are no longer ink but pixelation, books are no longer calfskin but PDFs. If Christ is the logos, the Word, how do we imagine Christ now that words themselves have changed their form?

So here is the question McLuhan sets for Catholics in the 21st century: How do we enflesh God in a new age, in a new environment, when our understanding of language, communication and reality has been transformed? And, although the technological changes of the past century feel new, that question is as old as the apostles.

Perhaps we can follow the wisdom of McLuhan, who, rather than moralizing about changes, thought it profound enough to observe them. And observation begins with our attention. Our attention: Where do we put that each day? And what will we see when we attend not just to the digital world but to the whole world around us: lovely, radiating, resistant to our scrolling fingers? Perhaps we can then begin to see more clearly who we are when we are consumed in the glowing digital globe we hold in our hands.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “A Prophet of the Media Age,” in the January 2023, issue.