Most reconsiderations of artists and works of art (Keanu Reeves, The Great Gatsby, “Vertigo,” to name just a few) take years or even decades to achieve. They were panned, now they are acclaimed. For the winner of this year’s Foley Poetry Contest, the “reconsideration” took a matter of days.

When "Letter to Myself While Learning to Read,"by Laurinda Lind, was submitted among the 600 or so poems we received this year—by the way, I encourage you to read the poem before reading this article about the poem—I read it, enjoyed it and put it on a list of poems to peruse again. This list eventually became 30 finalists, which I gave to our other two judges: Jill Rice, an O’Hare fellow at America, and James Torrens, S.J., a former America poetry editor.

I encourage you to read the poem before reading this article about the poem.

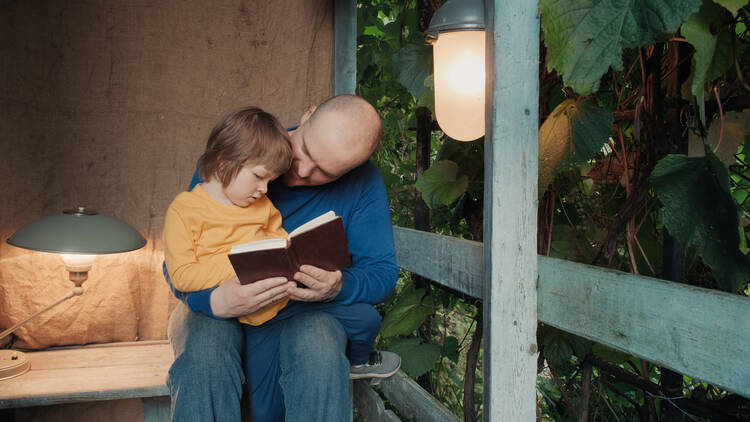

When we shared with one another our top five poems, only one of the judges had “Letter” on his list. I did not. “Letter” was a nice poem, but maybe too… romantic? Nostalgic? A kid sleeps on a porch in the summer; her dad reads her classic children’s books.

Nevertheless, I read “Letter” again, but it still did not do it for me. I went back to the other finalists, spent more time with one poem in particular, and picked it as the winner. “Letter” would not even be one of the three runners-up. The next morning, realizing I was still not entirely settled on the winner, I read “Letter” again. And again, and again. Each time I saw something new. Each time it sank deeper, its heft became more evident. It was not tossing out trinkets of romance and nostalgia; it was doing something deeper.

“Letter” quickly builds a world and opens the door ajar for us to gaze inside. A child isn’t just sleeping on the front porch like a summertime adventure: She is made to sleep there the entire season (which season, exactly, we are not told) because the visiting cousin has been given the bed. She is exiled, feeling like “an afterthought,” something we can all identify with. At some point or another, we have all been left out on the screened-in front porch of someone else’s affections, no?

And the father who treks out into the porch to help the child read—kindly, fatherly—but the only time he will ever do so. Why? Heidi, Robinson Crusoe, Swiss Family Robinson, the poet using these names not as biscuits thrown out to the nostalgic reader but because they align—even darkly—with the atmosphere of the story.

The poem pays out its narrative, loops us into its intrigues, leaves hints of resolutions, calls us to something beyond ourselves. All in 28 lines.

The poem pays out its narrative, loops us into its intrigues, leaves hints of resolutions, calls us to something beyond ourselves. All in 28 lines. “Letter” is just, how should I put it, it’s a really nice piece of writing. I am grateful on behalf of America to be able to award it the 2023 Foley Poetry prize.

We are also pleased to announce three runners-up, to be published in subsequent issues: “Lily, Lily, Lily,” by Nancy Clark, “Apology for Belief,” by Alex Mouw, and “Sappho,” by Beth Hinchliffe.

I am grateful for all the poets who submitted their work for the contest. Every year we get poems from all over the United States, and even across the world, about any number of topics:

“The Wreck of the Livonia” compares the deaths of several nuns in early Covid to “The Wreck of the Deutschland,” by Gerard Manley Hopkins.

“Civil Insubordination, or Where in Amerikkka Are Black People Free From Racism?” makes a chilling reference to the police shooting of Laquan McDonald by the Chicago police officer Jason Van Dyke.

One poet complains about a Twitter culture overwhelmed with virtue signaling, cancel culture, colleges having to change their mascots. But, interestingly enough, her demand to this culture seems to be less about opposing these ideas than transforming how they are expressed: “Explain ideas in coherent sentences,” she declares.

In 2023, it is almost quaint to consider that we might need to interface with God by text, when apparently God has sent ChatGPT to rule the world on his behalf. But the poem “Txt Mssg” to God (Fatal Error!/ Msg not received./ Pls snd Messiah again…) suggests God might still desire these kinds of prayers.

“Please send Messiah again.” Or, at least keep sending us works of art worthy of our reconsideration. They help us create a world any messiah would delight in saving.