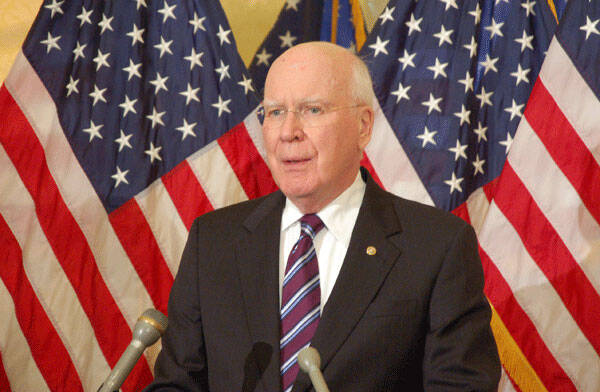

Review: Patrick Leahy, Senate stalwart

Like many great statesmen, Patrick Leahy is a chameleon. He is the small-town lawyer from Vermont who became a Democratic senator and moved comfortably for decades in the corridors of power. He is the “Watergate Baby” who challenged the old ways of doing business in Congress before evolving into one of the greatest defenders of the institution’s norms. On matters of both policy and cultural sensibility, the now-retired politician has a way of seeming simultaneously traditional and progressive.

These juxtapositions are at the core of The Road Taken, Leahy’s deeply personal new memoir. He writes lovingly about his family, his Catholic faith and his home state but seems focused largely on describing the Washington, D.C., that was—and what it has become.

Leahy is one of many Washington veterans who lament the erosion of old-fashioned give-and-take, across-the-aisle, art-of-the-possible parliamentary imperatives, laying blame for their decline largely at the feet of Donald Trump and his political allies. In the latter stages of the book, Leahy pillories Trump as a gasbag who never listens to anyone. In Leahy’s mind, the Trump administration succeeded primarily in unmooring the country’s governing institutions to the point of unworkability, putting piles of right-wing judges on the bench and setting the stage for the Jan. 6 insurrection.

Leahy concedes that the ignorance he witnessed from the MAGA crowd has crept into the Democratic side of the aisle. Citing the Amy Coney Barrett confirmation hearings for the Supreme Court, Leahy bemoans the counterproductive tactics some liberal and left-wing groups employed to oppose Barrett’s nomination. These included the idea that Democratic senators should have simply boycotted the hearings, which would have allowed for her confirmation without Barrett even facing serious questioning.

Despite Leahy’s extensive discussions of recent events in Washington, his memoir is not primarily a rumination on the recent past. It reads more like a requiem for a far-from-perfect, though basically positive, political culture. Nor is this a book thorough in its dissections of public policy or the legislative process. The Road Taken is a kind of catalog of dramatis personae, but not just of people, because Leahy also focuses on the places he inhabited.

Leahy spent eight terms in the Senate; many of the people he cites are well-known. Never does the appearance of a big figure come across as name dropping. If anything, he talks about his interactions with Washington bigwigs to show how much the kind of person inhabiting those positions has changed.

“Mr. Conservative,” Barry Goldwater, for example, takes the stage to stand up for the Supreme Court nomination of his friend and longtime colleague Sandra Day O’Connor against criticism from ideologues within his own party. O’Connor went on to be confirmed 99-0, a tally that would be unthinkable today.

Leahy writes with great warmth about three prairie legislators, all with distinct political inclinations, who mentored him upon his arrival in Washington: Bob Dole, George McGovern and Hubert Humphrey. As a native Vermonter, he related a great deal to each of their rural upbringings and admired their respective commitments to working in a bipartisan fashion to achieve shared policy goals. Though Leahy never discussed it explicitly, his memoir demonstrates the degree to which the political diversity that existed in Washington several decades ago has dissolved in favor of a politics of litmus tests.

Leahy spends considerable time discussing his life as a Catholic in Vermont, historically a Protestant stronghold. His father was an Irish Catholic Democrat in a state where their numbers were few and far between. Leahy’s education came entirely through Catholic schools. He attended parochial elementary and secondary schools in Montpelier before spending his undergraduate days at St. Michael’s College in Colchester, Vt., studying government at the Edmundite institution. At St. Michael’s, Leahy found a mentor in Ed Pfeifer, a historian who had attended the same schools that he had in Montpelier. Pfeifer played a significant role in shaping Leahy’s interests and aspirations, “challenging us to think critically, test our ideas, and debate relentlessly.”

Leahy concluded his education at Georgetown Law School. Well before attending law school in Washington, Leahy caught the “political bug”—a product of both his upbringing and formal education. In 1960, Leahy knocked on doors for John F. Kennedy. He heard time and again from Vermont voters who, even though they were not exactly fond of Richard Nixon, felt that they had to vote for the Republican because Kennedy was a Catholic. Even after Kennedy’s historic election win, this lesson about voter prejudice remained front and center in Leahy’s mind.

When Leahy decided to run for the Senate in 1974, not only were his youth (he was 33) and party affiliation considered detriments to his electability; his Catholic faith was still also considered a hurdle, nearly 15 years after Kennedy was elected president. A castle keep of Yankee WASPdom, Vermont had elected its first Catholic governor, Tom Salmon, only two years earlier, but Leahy benefited from the “throw the bums out” mentality of the first election after Watergate. The Vermont press dubbed him “the accidental senator”—the election of a Catholic in that state being no small part of the “accident.”

Turning to more recent times, Leahy expresses particular ire with “the convenient, sudden interest of so many non-Catholics in defending the faith,” pointing out episodes of Republican politicos advancing their policy goals by painting their opponents as anti-Catholic bigots on issues such as abortion. He seethes at Republicans such as Rick Santorum and Josh Hawley (who was raised Methodist but later joined a Reformed church), whom he describes as explaining to him what political opinions made someone a “real” Catholic—itself a bizarre manifestation of litmus-test political culture.

Shockingly, the event that made Leahy a statewide figure in Vermont, giving him sufficient name recognition and reputation to challenge for a Senate seat, receives nary a mention. During his tenure as state’s attorney in Chittenden County (Vermont’s most populous county), Leahy took down a villainous narcotics agent named Paul Lawrence who planted drugs on dozens of young Vermonters and put piles of innocent people in jail. Leahy and his squad caught Lawrence red-handed, and the one-time Green Mountain State “super cop” found himself behind bars. Governor Tom Salmon ended up pardoning 71 people convicted based on Lawrence’s testimony.

While The Road Taken offers an incomplete look at the legacy of the senator from Vermont, it reveals a series of often compelling snapshots of his life and times. At its best, it reads like an acquaintance’s yearbook, replete with the signatures and recollections of other familiar faces.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “Senate Stalwart,” in the May 2024, issue.