If I ever got stuck behind someone who was nearly seven feet tall at a Dead & Company show, I imagine I would be pretty annoyed. But perhaps the only exception would be having the honor to have my view blocked by the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Famer Bill Walton, who attended over 1,000 Grateful Dead shows over the course of his larger-than-life existence. He died on May 27 at the age of 71 after a battle with cancer.

Hailing from the same state as The Dead, Walton grew up in La Mesa, Calif., and first played organized basketball at Blessed Sacrament Elementary School under the guidance of local firefighter Frank Graciano, who realized Walton’s potential from a young age.

Walton called Graciano, a volunteer coach, “as important a person in my life as there’s ever been” and “a person who selflessly gave up his life so other people could chase and fulfill their dreams.”

You would be hard-pressed to find a person that emulates Walton’s sincere gratitude for their middle school basketball coach, but that was Walton’s nature—grateful to the core.

After graduating from Helix High School, Walton went on to U.C.L.A., where he played for a slightly more high-profile figure in the basketball world: John Wooden.

Wooden, a deeply religious man on his own journey to becoming a basketball icon, molded Walton into one of the greatest college basketball players of all time. Walton’s tenure as a Bruin concluded with an astonishing 86-4 record and two national championships.

But Wooden also experienced what Walton was like off the court early in his life: a man of deep personal conviction who took great interest in striving for the common good.

In an interview with America, Amir Hussain, a professor of Theological Studies at Loyola Marymount University with a deep reverence for the coach to whom he refers as the “blessed” John Wooden, recalls a section of Wooden’s memoir on Walton’s pushing back against a team policy that barred facial hair:

Coach Wooden: “Bill, have you forgotten something?”

Bill Walton: “Coach, if you mean the beard, I think I should be allowed to wear it. It’s my right.”

Coach Wooden: “Do you believe in that strongly?”

Bill Walton: “Yes, I do, coach. Very much.”

Coach Wooden: “Bill, I have a great respect for individuals who stand up for those things in which they believe. I really do. And the team is going to miss you.”

Walton ended up shaving later that day.

“I loved that. Bill had the right to have a beard, but not the right to be on Coach Wooden’s team,” Hussain said of the meeting between two principled characters.

Hussain also noted how Walton’s other demonstrations of his beliefs made him “representative of student movements in the 1970s, which we seem to forget happened in the current moment of student movements.”

In the spring of 1972, Walton was arrested for peacefully demonstrating against the Vietnam War on U.C.L.A.’s campus, a Goliath in stature who still believed in nonviolent activism.

“Protesting is what gets things done,” he said. “The drive for positive change requires action. The forces of evil don’t just change their ways.”

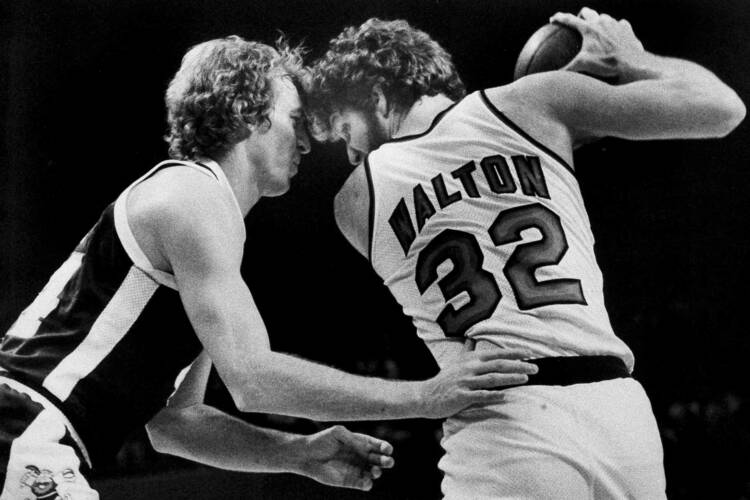

After Walton’s playing career at U.C.L.A. concluded, he was selected first overall by the Portland Trail Blazers in the 1974 N.B.A. Draft, leading them to a championship just three years later. He followed that up by winning the league’s Most Valuable Player award in 1978.

But while he initially set the league ablaze with his play, disastrous luck with injuries soon plagued Walton and affected his physical and mental health. Walton underwent an unfathomable 39 surgeries during his time in the N.B.A., causing him to miss 762 games. If he had stayed healthy over the course of his career, Walton could have been even more of a household name than he already is.

“I wanted to be the best. I wanted to win everything. And I idolized [Bill] Russell, Wilt [Chamberlain], Oscar [Robertson], Kareem [Abdul-Jabbar]. But my body would not carry me to my dreams,” he once said.

Walton eventually pursued a career in broadcasting in the early 2000s; his whimsical commentary and his passionate love for the Pac 12 conference will long be remembered.

Long after his playing days were over, Walton’s injuries still took a massive toll on him. In 2008, his spine collapsed, and he endured a grueling two-and-a-half-year recovery period which left him practically immobile; he spoke about contemplating suicide during this time.

But even during his darkest moments, the man with a radical sense of optimism credited one massive influence with keeping his light alive: The Grateful Dead.

Walton titled his 2016 memoir, Back from the Dead, as an homage to the band and frequently spoke on how the group helped him to renew his lease on life: “Over the course of my basketball career I’ve had many many setbacks and many pitfalls that I’ve stumbled into. Something that I’ve learned and I’ve received a lot of encouragement and help from my friends, particularly in The Grateful Dead, [is] don’t look back. Just keep going and something good will happen," Walton said.

One person that shared Walton’s vision for the world is Jane Morrissey, S.S.J., a Sister of St. Joseph who is well-known in Mount Holyoke, Mass., for her work with Homework House, a free academic support program for children.

Walton was frequently and generously involved with Sister Morrissey’s activism, donating autographed memorabilia for the organization to raffle off as recently as 2022.

“Sister Jane is a shining star, a beacon of hope. She makes us believe that the fight to get to tomorrow is worth it,” Walton said of the activist nun. “She has the willingness, the calm, poise and confidence to stand up to all the absurd nonsense all of us face every day.”

I may have not met Bill at that Dead & Company show in San Francisco, but I will never forget seeing him shown on the big screen next to the stage, as much part of the band’s victory lap as any of the musicians.

Members of The Grateful Dead have evinced a strong belief that there is something greater waiting for us after we pass. In his goodbye message to his longtime friend Bill, The Dead guitarist Bob Weir wrote: “Bon voyage ol’ buddy. We’re sure gonna miss you—but don’t let that slow you down…”

“I wanted to be a basketball player, be a hippie, on tour with The Grateful Dead, be an adventurer. I didn’t spend my life trying to be the richest guy on Earth,” Walton once said about himself. I will never forget Walton’s joyful pursuit of all the good things the world has to offer, a true model of a life well-lived.