Sometimes I wonder about the apostles’ families. We know they had them: Peter, for instance, was married, and James and John’s mother was a disciple of Jesus. We also know that, while the apostles may not have cut their families off entirely, they had to separate themselves to follow a higher call. As Jesus says in one of those particularly challenging Gospel verses: “If any one comes to me without hating his father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters, and even his own life, he cannot be my disciple” (Lk 14:26).

There’s a reason why the heroes of fairytales and comic books are so often orphans: It’s easier to embark on a risky adventure if there’s no one at home worrying about you or at your side urging caution. But our real-life experience is closer to the apostles’. We take risks, sometimes defying the people who love us most and only want our safety and happiness. Or, on the other side, we may find ourselves struggling to hold our tongues as we watch our loved ones enter into some dangerous undertaking. But some risks are worth taking, some causes worth putting ourselves on the line. So what do we do when we find ourselves, or someone we love, torn between convictions and relationships?

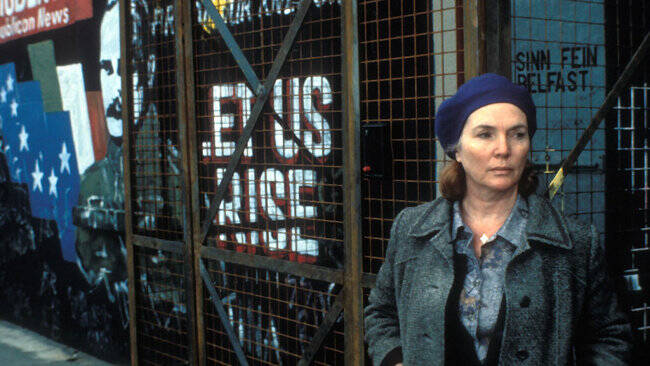

Two mothers find themselves in that exact quandary in “Some Mother’s Son” (1996), a dramatization of the 1981 Irish hunger strike directed by Terry George and written by George and Jim Sheridan. The historical strike, led by IRA officer Bobby Sands at Maze Prison in Northern Ireland, challenged the British government’s decision to treat paramilitary prisoners as criminals instead of prisoners of war. The strike lasted for months and resulted in 10 strikers dying of starvation.

The film follows Kathleen (played by Helen Mirren) and Annie (Fionnula Flanagan), the mothers of two fictional IRA strikers Gerard (Aidan Quinn) and Frank (David O’Hara). Kathleen is a teacher at a Catholic school, well-mannered and apolitical. Annie is rougher around the edges, confrontational and fully supports the Irish republican movement. Despite their differences, they find themselves in the same position, watching from the outside as their sons prepare to make the ultimate sacrifice. As the strike wears on and the young men become incapacitated, Kathleen and Annie are faced with a difficult choice: exercise their right to have their sons forcibly fed and save their lives, or respect their wishes to see the strike through.

Kathleen and Annie learn a great deal from each other. As the film progresses, Kathleen becomes bolder and politically active; Annie, full of sorrow and rage following the killing of her older son by British soldiers, finds some measure of healing in their friendship. But when faced with this ultimate choice, the core philosophical difference between them is laid bare. When a priest begs Annie to help end the strike, she’s clear that for her it’s not a choice. Her love for her son and their shared commitment to Irish freedom are inseparable; going against his wishes to end the strike would be an unforgivable betrayal. Kathleen, on the other hand, struggles to reconcile her newly awakened political consciousness with her overpowering love for her son. It’s an impossible position for any mother, any parent, any person; you sympathize with them both, even if you only agree with one of them.

I did not end up making a definite decision about who was “right.” The decision that Annie and Kathleen face is not a choice I have ever had to make, and—as a parent and a son—I can’t say for sure what I would do, or that my choice would necessarily be the right choice for everyone. I’m not endorsing relativism, but instead, I acknowledge that we all have to negotiate a balance between our commitments to our convictions and relationships.

Jesus’ charge to the apostles is also aimed at us; we are not called to leave home and follow him around the countryside, but we do need to discover what it means in our time and context. At heart, it’s not about “hating” our families or turning our backs on them but about having interior freedom—an openness to follow God’s call that is unimpeded by any earthly thing, even our love for and obligation to our families. Commitment to one’s family and the need to follow God’s call don’t always come into conflict (family life is, after all, a vocation) but when they do, they offer some of the truest and most challenging tests of our faith. In those moments we can only hope that, like Kathleen and Annie, we will make choices rooted in love.

“Some Mother’s Son” is streaming on Hoopla