The genius of James Joyce: Sin, guilt and the redemptive power of laughter

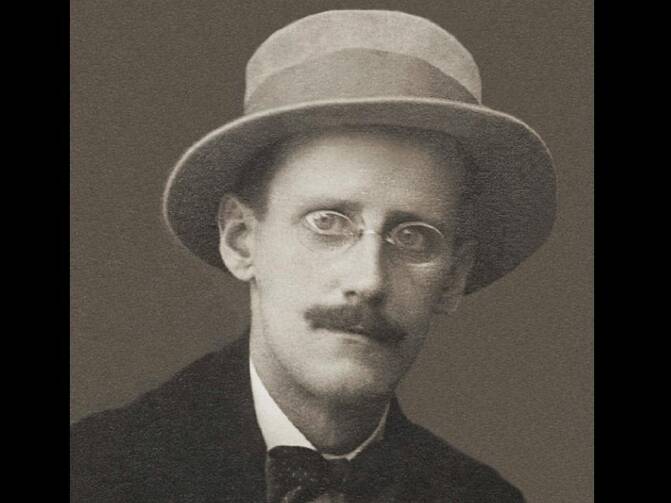

Reenacting the Fall of Adam and Eve with his siblings, a young James Joyce played the part of the devil, “wriggling around on the floor with a long tail made of a rolled-up towel.” In her posthumous biography James Joyce: A Life, Gabrielle Carey grants that sin was one of Joyce’s lifelong obsessions. The young author himself admitted that a “special odor of corruption” surrounds his early stories in Dubliners, but in a letter to his wary publisher Grant Richards, Joyce justifies the’ “scrupulous meanness” of the stories on the grounds that Joyce “is a very bold man who dares to alter in the presentiment, still more to deform, whatever he has seen and heard.”

In this view of literary realism, what is most real is the ugly underbelly, the ubiquitous “ashpits and old weeds” that make our world a cosmic tragedy. But more pertinent, Carey says, to our understanding of the overall trajectory of Joyce’s literary canon is a paradoxical notion at the very heart of the faith Joyce lost: felix culpa, or the Catholic theological tradition that finds happiness in the fallen state of humanity, wherein the Fall brought Christ to humanity and ushered in the possibility of the Resurrection.

For Joyce, humanity’s faulty condition says Carey, “is happy because faults, errors, mistakes and misunderstandings” are the birth of comedy. Joyce wrote novels meant to make us laugh, for laughter is “the essential relief from life’s sufferings,” as Carey writes—a purgative literary medicine for a litany of afflictions.

Faithful to the form of Joyce’s “grocer’s assistant's mind,” Carey’s biography is not chronological but is rather composed of lists of the fiascos that followed Joyce until he narrowly escaped the Nazi sweep through Paris—only to die in Zürich, undone by a duodenal ulcer.

His debut Dubliners sold only 370 copies, 120 of which Joyce had purchased himself; the collection, first halted by two distinguished publishers, earned no more than two-and-a-half shillings in royalties. Self-exiled from Ireland to Trieste, Italy, the young Joyce was robbed of his severance pay the very day he resigned from Nast Kolb Schumacher Bank. Nora, Joyce’s wife, stayed with him until death, but their union was preserved in part by her perpetual threats to—alternately—leave him, baptize the children or burn his manuscripts if he failed to cure his Irish taste for liquor. He failed. She stayed, and did not set his writing afire.

When his mother died, Joyce’s drunkard father sent a telegram that confirmed Joyce’s jocose sense that, “most human communication is miscommunication”: “Nother dying, come home. Father.” But the real-life pun (“another dying”?) provided no solid solace. If Joyce named his father’s abuse as a major cause of his mother’s death, he counted his own “cynical frankness of conduct” as a considerable reason she was in the coffin. The guilt was something awful, and he transposed it onto his alter ego Stephen Dedalus in Ulysses, seen most especially when the character Buck Mulligan muses that Stephen may have killed his own mother: “to think of your mother begging you with her last breath to kneel down and pray for her. And you refused. There is something sinister in you.”

If even overbearing Buck moves on while a “tolerant smile curled his lips,” Stephen is immediately visited by “her wasted body within its loose brown graveclothes giving off an odour of wax and rosewood, her breath, that had bent upon him, mute, reproachful, a faint odour of wetted ashes.”

Nearly 600 pages later, his guilt still simmers: “They say I killed you, mother,” he protests to her ghost, “Cancer did it, not I. Destiny.” With a “green rill of bile trickling from the side of her mouth,” she bids him “Repent, Stephen.” Yes, Joyce’s troubled conscience could tally the time he sent her the guineas he got for writing a review of Ibsen. But, to cite just one counter-case Carey gives us, “she sold a carpet so she could wire money to her brilliant eldest”—once nicknamed “Sunny Jim” for his “easygoing disposition.” Her Sunny Jim was now troubled in Paris, putting the family further in debt as he pored over Aristotle in the library.

If Stephen Dedalus bounds through Ulysses from one satirical episode to another, untouched by comic grace that could reconcile him with his mother, does his search for a father fare better—or fail? Near the novel’s end, when Stephen is about to be beaten and maybe jailed, Leopold Bloom intervenes and drags the drunken Stephen home, where the son and the spiritual father find a kind of communion: “His attention was directed to them by his host jocosely, and he accepted them seriously as they drank in jocoserious silence Epps’s massproduct, the creature cocoa.”

The Eucharistic resonances are at least partially jocose. But for Stephen—who has just identified his host as “Christus or Bloom his name is or after all any other, secundum carnem”—the meal is both comic and serious, secularizing and yet scintillating with an unmistakable spiritual significance. As Joyce confessed in his Trieste notebook under the heading “Jesus”: “His shadow is everywhere.”

After their shared, sobering drink, in one of world literature’s most anticlimactic exits, Stephen fades out of the novel, refusing Bloom’s gracious offer of a place to lay his head. But before the two part, they step outside and pee side by side, beholding “The heaventree of stars hung with humid nightblue fruit.” This juxtaposition of the arresting beauty of nature and common urination—is it meant to make us laugh, or is it an anti-sentimental expression that the son and the father are finally one?

Although after his 1916 collection of poems, Chamber Music, Joyce turned his pen to prose, the death of his father in December of 1931 and the birth of his grandson Stephen James Joyce brought him back to poetry in 1932. His poem “Ecce Puer” offers a play on Pontius Pilate’s “Ecce Homo” (Jn 19:15) that resolves on this plea:

O, father forsaken, Forgive your son!

Ralph McInerny notes that a painting of Joyce’s father hung in the son’s apartment, and “in it, the old man has the look of someone about to tell a lie, or sing a song, or ask for another drink.”

When his father died, Joyce, “being a sinner myself,” confessed an undying fondness for the man who made so much trouble for their family. The calendar he drew up after the funeral captures the strange fusion of grieving and punning:

Moansday

Tearsday

Wailsday

Thumpsday

Frightday

Shatterday

Although Joyce’s patron Sylvia Beach—the owner of the Shakespeare and Company bookstore in Paris—raised enough subscriptions to underwrite Ulysses (donors included not only expected intercessors like Ernest Hemingway but also surprising benefactors like Winston Churchill) when the writer finished the final pages of Molly Bloom’s famed soliloquy, critics were not kind.

Virginia Woolf shrank the behemoth of a book—written from 18 different points of view—as “an illiterate, underbred book…the book of a self-taught and working man, & we all know how distressing they are…” Eventually, in the United States, Judge John M. Woolsey both praised and damned the novel in one swoop: If he lifted the indecency ban on the book by determining that it did not contain “dirt for dirt’s sake,” he judged that Ulysses, rather than inciting lust, should likely be consumed with a tall glass of Alka-Seltzer. Both missed what Joyce intended: Ulysses was a comedy.

Life at the time was less comic. When Nora and the Joyce children Giorgio and Lucia returned to Ireland from exile in Paris against Joyce’s warning, they were met by the IRA, who mounted guns aimed at their bedroom windows. On their trip back to Paris, snipers set upon the train, putting his wife and children in the crossfire.

Joyce finished Finnegans Wake after several excruciating eye surgeries performed sans general anesthesia and aided, no joke, by blood-sucking leeches—as World War II loomed. (“Later,” says Carey, “he described himself as an international eyesore.”). As the war drove the Joyces out of Paris to Zürich, the half-blind novelist peered through “the window of my soul” to witness the reception of his painstakingly put-together Irish Wake. His friend Paul Léon told Joyce’s patron Harriet Shaw Weaver that while it was “impossible to deny that he has acted according to his conscience,” the book which cost him “almost all of his substance, physical and spiritual, moral and material” was “likely to be received with derision by his ill-wishers and with pained displeasure by his friends.”

Weaver had given Joyce a comic windfall of a million dollars, meant to support him until the end. But when his dancer-daughter Lucia was diagnosed with schizophrenia, he had to reroute three-fourths of the money to the costly care that promised to cure her. Joyce took her all the way to Carl Jung, whose psychoanalysis of Ulysses found that “the whole work has the character of a worm cut in half, that can grow a new head or a new tail as required.” Joyce’s reply? “He seems to have read Ulysses from first to last without a smile.”

What would it mean to fulfill the paradoxical maxim of Joyce’s one-time secretary Samuel Beckett from his story “Westward Ho”: “fail better”?

Carey sees comedy as the skeleton key to Joyce’s work, joking (but only partly) that his misunderstood Finnegans Wake is “a highly effective anti-depressant.” A testimony seen on Tiktok tells the flip side of the joke: “has anyone read finnegans wake? my therapist gave it to me to help w my intrusive/obsessive racing thoughts. I just started reading . . . it makes my mind so clear I’ve NEVER experienced silence and finally know what it feels like. 10/10 recommended. Seriously.”

Although Joyce described Finnegans Wake as his “experiment in interpreting the ‘dark night of the soul,’”its character the Gracehoper is “always jigging ajog, hoppy on akkant of his joyicity.” Is the levity of Joyce’s art a troubling attempt to cope with that dark night, or a true transcendence of life’s sea of troubles? By juxtaposing a lifetime of sufferings with the comic spirit of the author’s corpus, Gabrielle Carey bids the reader decide whether such habitual “joyicity” is a false surrogate—or a fitting analogy—for grace.

In a coda, Carey tells us that Nora “died in a convent hospital and was buried beside her husband,” and—adds Ralph McInerny in his essay on Joyce—“went to Mass, said her beads, received the last sacraments. No doubt she prayed for the bibulous, skeptical, loving genius.”

No doubt, on this Bloomsday, we too ought to beg from Our Father—whose solicitous hounding of Joyce far surpassed Bloom’s care for the alter ego Stephen—the saving epiphanies that alone can mend our talent for ingenious miscommunications. As we read in Finnegans Wake:

Loud, heap miseries upon us yet entwine our arts with laughters low!