This is part two of a series on Francis Ford Coppola’s Godfather Trilogy. You can read my reflection on the original film, “The Godfather” (1972), here.

The American Dream is a dream of freedom: the freedom to determine your own future and the freedom to build something you can leave behind for your children. Few cinematic characters embody that dream more—or lay bare its potential for corruption—than the Corleone family in Francis Ford Coppola’s “Godfather” trilogy. In the middle chapter, “The Godfather Part II” (1974), we learn the family’s origins while watching them decline into violence and betrayal in the present day: the American Dream putrefying into an American nightmare.

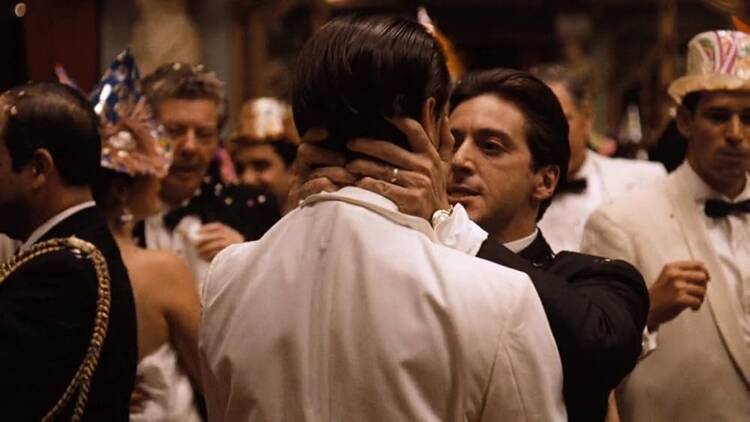

Following the events of the first film, Michael Corleone (Al Pacino) is now firmly established as the head of his crime family, succeeding his late father Vito, played in the original by Marlon Brando. He has a growing family, makes deals with senators and assures his wife Kay (Diane Keaton) that he’s going to make the Corleone operation a legitimate enterprise. But he has also partnered with the aging, vicious crime lord Hyman Roth (Lee Strasburg) to expand his business, and struggles to manage discontents within his organization, including his feckless brother Fredo (John Cazale). As conspiracies grow and blood begins to spill, Michael reveals that there are no limits to what he will do to hold onto power.

In a parallel storyline told through flashbacks, we follow Vito from a boy (Oreste Baldini) forced to flee Sicily after the murder of his family, to a refugee on Ellis Island, to a young family man (Robert DeNiro) trying to make ends meet on the streets of turn-of-the-century New York. Little Italy is close-knit but impoverished, and preyed upon by the swaggering extortionist Don Fanucci (Gastone Moschin). After unjustly losing his job, Vito becomes a small-time criminal with friends Clemenza (Bruno Kirby) and Tessio (John Aprea). As his power and capacity for violence grow, we watch him become the imposing Godfather of the first film.

The rot in the Corleone family is there from the start—we are, after all, talking about a crime family—but Vito’s intentions are as good as they can be in this context. He wants to provide for his family, to give his children the life that he never had and to protect his community from wolves like Fanucci. And so he becomes a wolf himself. Vito is both feared and genuinely respected: a powerful man who uses his influence to protect others (we see him shield a widow from eviction, for example), and only employs violence when necessary. Power, for him, is a means to an end.

But for Michael, power is its own end. He says he’s doing everything for the family, to protect the life they have built, but his actions tell a different story. Michael is the dark embodiment of American self-determination, a man who wants to do whatever he wishes without consequence or criticism. All threats to his dominion, even members of his own family, must be destroyed.

Michael has inherited his father’s restraint, but while Vito’s restraint marked him as a man of careful strategy and considered action, Michael’s reveals him as cold. He loves his family but he can’t see that he values them as fixtures of his empire, not people. When they cease to play their assigned role, they become disposable. The transition from Vito and Michael is like the gradual heat death of the universe, the slow draining of warmth from all things. You see this in their relationships with violence: Vito kills two people in the film, both in return for cruel acts, both by his own hand. Michael kills many more, often for dubious reasons, and never directly: Even the most personal murders are carried out by underlings.

Despite his performative Catholicism, Michael puts more stock in the American vision of freedom than the Christian one. Christian freedom has ends beyond itself, as St. Pope Paul VI wrote in “Gaudium et spes”: “For God has willed that man remain ‘under the control of his own decisions,’ so that he can seek his Creator spontaneously, and come freely to utter and blissful perfection through loyalty to Him.” We are called to choose and do what is good on our own initiative, aided by grace. Our freedom connects us to others and, eventually, leads us to union with God.

Paul VI contrasts this “authentic freedom” with an atheistic freedom in which man is “the sole artisan and creator of his own history.” This is what Michael wants, perhaps all he has ever wanted. In the first film I interpreted Michael’s distance from his family as a sort of moral stance, a discomfort at their criminal dealings; “Part II” implies that Michael’s true desire was to chart his own course, free from his father’s influence. Now that he has the power to exercise his will, he pursues it without any thought to the cost paid by others.

In the end, Michael gets exactly what he wants. He is—at least for the moment—all-powerful and unthreatened. And completely alone.

“The Godfather Part II” is streaming on Paramount+.