“Beauty will save the world.”

These are the words that kept running through my mind as I made a pilgrimage through the current exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300-1350.” A vast space, dark and brooding, houses the exhibition—the better to see the images on display, the blazing blues and the gorgeous golds beautiful and bracing against a black backdrop. But the darkened space, punctuated by columns evoking the medieval cathedral of Siena, also seems a forewarning of the times to come.

In 1348 the Black Death would strike Siena, rage for six months and kill half the city’s population. Hundreds of people would be stricken with plague each day, suffer the growths of buboes in their armpits and groins, and die an agonizing death. Family members would abandon the sick for fear of catching their death, and burial would be left to those willing to risk their own safety—including the saintly Catherine of Siena—by dragging swollen corpses to the ditch dug outside the city and covering them in dirt, leaving room for the bodies to come the next day. To be alive in Siena in 1348 was an unimaginable nightmare.

Set against this horrific history is the work of four extraordinary artists—Duccio di Boninsegna, Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti, and Simone Martini—two of whom would die in that plague. But before they died, and perhaps unbeknownst to themselves, they created works of transcendent and lasting beauty that would serve as an antidote to the disease, death and destruction that would soon befall their beloved city and, indeed, the world beyond.

Communing With the Saints

The one hundred objects on display—paintings alongside sculptures, metalwork and textiles—tell the stories and feature the figures familiar to Catholics, both medieval and modern. The paintings depict Jesus and Mary, of course, and the events of their extraordinary ordinary lives, including Jesus as a baby in his mother’s lap reaching up to touch her face (Duccio di Buoninsegna, 1340) and Jesus nursing at his mother’s breast (Ambrogio Lorenzetti, 1325)—two tender Madonnas set beside the carving of Jesus suffering horribly on a crooked cross while his desolate mother looks on (Guccio di Mannaia, 1310-20). His life, their lives all of a piece: the joy of birth, the inevitability of suffering and death.

My favorite painting, placed at the end of the exhibition, clearly occupying pride of place, is Simone Martini’s “Christ Discovered in the Temple” (1342). The painting (see Page 51) depicts Mary and Joseph disciplining Jesus for going to the temple without telling them. The focus is on their parental concern for his safety, their relief combined with their anger: Joseph’s stern face, showing his disappointment at his foster son’s thoughtlessness; Mary’s mild correction, gesticulating as she holds a book in her hand, as if to tell him she understands his love of the law but also to say how worried she was; and young Jesus, a resentful adolescent, hugging himself with his hands and arms, a defensive posture, silently suffering the onslaught from his benighted and overprotective parents. It is a scene from the life of any family, Sienese or American, 14th century or 21st. The painting is startling in its honest and poignant depiction of universal family dynamics, offering an interpretation of a well-worn Gospel story that I had never seen before.

I pored over this painting for a long time, along with my friend Maria, who accompanied me on my pilgrimage. As veteran mothers of sons, recalcitrant and otherwise, we immediately recognized it as a depiction of episodes from our own lives. This is Jesus, Mary and Joseph’s story—but it is also ours, told through images rather than words, across the distance of 700 years. I don’t know if Martini himself was a father, but I imagine he must have been.

Between Duccio’s “Madonna and Child,” the first piece of the exhibition, and Martini’s fresh, new version of the Holy Family, there are many other powerful depictions of Gospel stories and lives of the saints, most notably multiple Annunciations with their resplendent angels and stunned Marys. It was not lost on me that my friend and I, two Catholic women christened Maria and Angela—our names bespeaking this story of the eruption of the news of salvation into a broken world, brought to Mary by an angelic messenger—had chosen to spend the day among so many Annunciations. It seemed natural and almost inevitable, from the first moment we saw the advertisement for the exhibition, that we would go to see it

As we moved from station to station, we were given fresh glimpses into other events in Christ’s life. A series of panels painted by Duccio as part of the magnificent Maestá, the double-sided altarpiece once housed in the Cathedral of Siena, tells a horizontal narrative, offering moving depictions of Jesus’ temptation by a bleak, black devil, Jesus’ calling of the disciples (who gingerly hold their net full of fish), the marriage feast at Cana (with his mother strikingly seated at the head of the table), Jesus with the woman at the well, Jesus healing the man blind from birth, the Transfiguration, and the raising of Lazarus. The latter is particularly touching, depicting Jesus flanked by Lazarus’ sisters, the practical Martha watching him in wonder, the mystic Mary who has fallen to her knees, and an unidentified young man in Sienese dress standing close to the open tomb and holding his splendid gold cloak up to his nose to mask the smell from the grave.

These are details drawn from life, as well as from the stories handed down to us, generation after generation, refreshing them. There is nothing clichéd, rote or static about these depictions. They are a re-envisioning, charged with the imagination of the artist and brought to life.

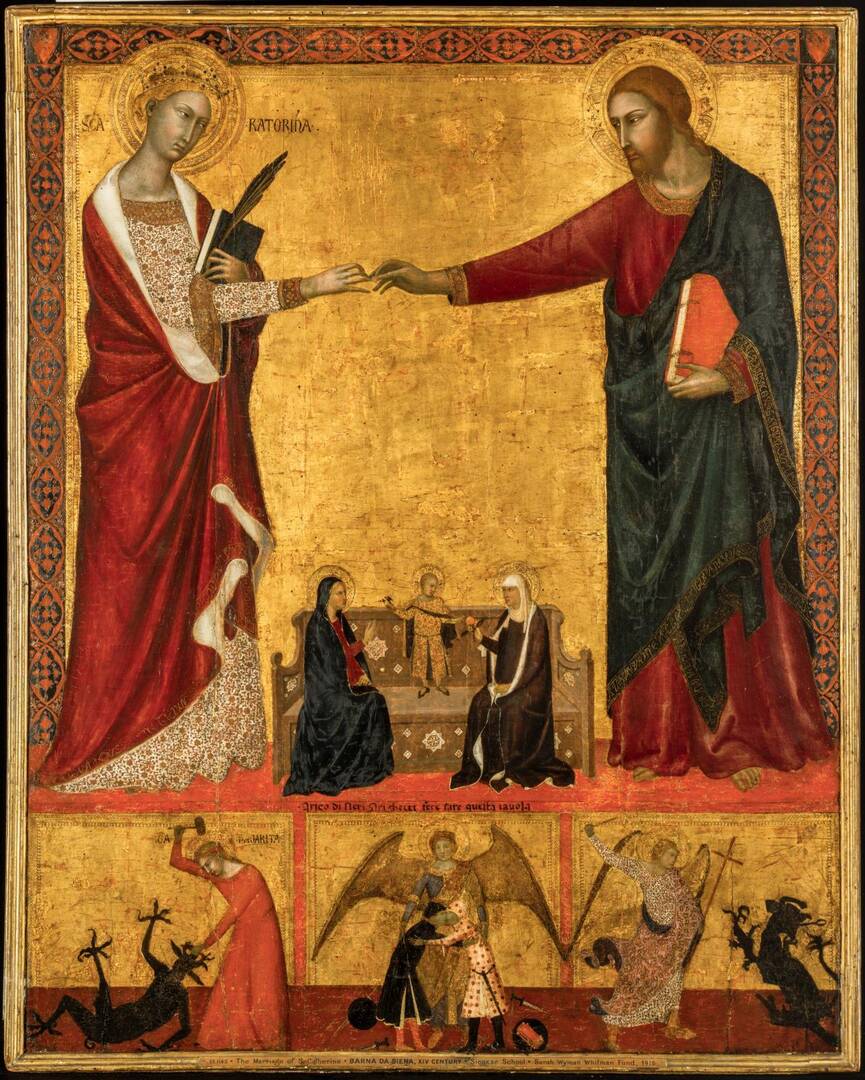

Another of my favorite pieces depicts “The Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine” (Barna di Siena, 1340) (see Page 52), the patron saint of Siena who betrothed herself to Jesus as a young girl, spent her life caring for the poor and the sick, and offered advice to the pope (some of which was helpful, some not). One of the three frames below the depiction of Christ placing a wedding ring on Catherine’s finger shows St. Margaret mercilessly hammering the devil—that same bleak, black figure that tempted Christ in scenes before. It is a cheering sight in all times, but especially in dark times, to see a holy woman so wonderfully empowered. These are paintings created by artists who believe in the power of the saints to defeat evil in the here and now and make our world a better place.

The Zone of Beauty

These re-imaginings of received stories are as vivid in our own time as they were in 14th-century Siena—and I trust their vivid depictions of faith served the Sienese people well in the years of plague that would follow their creation. I like to believe that the church and the art it housed—with those blazing blues and gorgeous golds—constituted an inviolable zone of beauty, a kind of inner sanctum that vied with the ugliness of the Black Death that raged outside. And when the ugliness did occasionally enter in the form of the black devil, he got pushed aside by Christ, hammered by St. Margaret.

Even for us, who, thank God, are not living in a time of plague, the visions presented by these paintings are utterly arresting. I couldn’t look enough, nor could my fellow museum-goers—staring hungrily, eating with our eyes, as if trying to internalize them and take them with us, snapping photos of the pieces so we could do just that. Lucky us, for the Sienese had no such technological ability. They would simply have to rely on memory—or, more important, the memory of how these pictures made them feel: closer to God, certain of heaven, newly in love with Jesus and Mary, looking forward to an afterlife that will be so much better than this one.

We, on the other hand, in 21st-century New York, were gazing at these paintings from a very different place, geographically, temporally and spiritually. The weather outside that day was lovely and fine. Anyone watching us—the watchers—could see that we were well fed and well heeled, taking for granted the fact of being alive. We were not desperate to believe in a faith that would save us. Many of us at the museum on any given day, in fact, don’t believe in God, let alone in the people being depicted so lovingly in these paintings and carvings. And yet they—we—still come. Why? I wondered.

Listening to the conversations taking place in the gallery, mostly in reverential whispers, I gathered that many of the people present were interested in history—or, more specifically, in art history—in artistic technique, in Italian culture, in beautiful objects of any kind. People love Greek sculpture, even if they don’t believe in Greek gods. We love the stories they tell us about ourselves. There is truth in them, even if the stories themselves are invented.

But if one does believe in God, has even a modicum of faith and has been formed as a Catholic—if one recognizes these people and their stories as companions of one’s childhood, fellow pilgrims along the journey toward eternity—how much richer the experience. These artistic renderings constitute a feast for the heart as well as a feast for the eye, reminding us of the foundations of our faith and the stories that first stirred our imaginations. The precious details (Jesus touching his mother’s face, the man with the cape over his nose, that spoiled adolescent Jesus) humanize these larger-than-life figures, bring them into the room with us and also put us in the room with them. Art grounds what can sometimes seem an abstract faith in the real, appealing to our senses, bringing home to us in an experiential way the truth of the Incarnation.

“Beauty will save the world,” Dostoyevsky once wrote. Maybe not from plague, and maybe not from politics (which seems to be the plague of our current moment). But even the darkest forces cannot defeat the power of the human imagination—and, in this case, the Catholic imagination—to redeem a broken and suffering world, reminding us of our people and our story: that Mary says yes, Christ is born, the dead will be raised, saints walk among us and the devil always gets hammered.