At the New York International Antiquarian Book Fair, you are guaranteed to find the following: a signed first edition of your favorite book, a celebrity (or two) and Bibles. The latter was what I had come to see on a recent visit to this year’s show at the New York Armory. Unlike other attendees, though, my goal was not to purchase one of these high-ticket Bibles but to answer a nagging question. I wanted to explore what it was about physical Catholic texts that makes them so compelling to a modern audience, religious or otherwise.

My experience at the fair yielded answers, both surprising and expected. Five offerings in particular embodied the history of Catholicism from the exiled to the dominant, from the reviled to the exalted and the public to the personal.

(In) the beginning

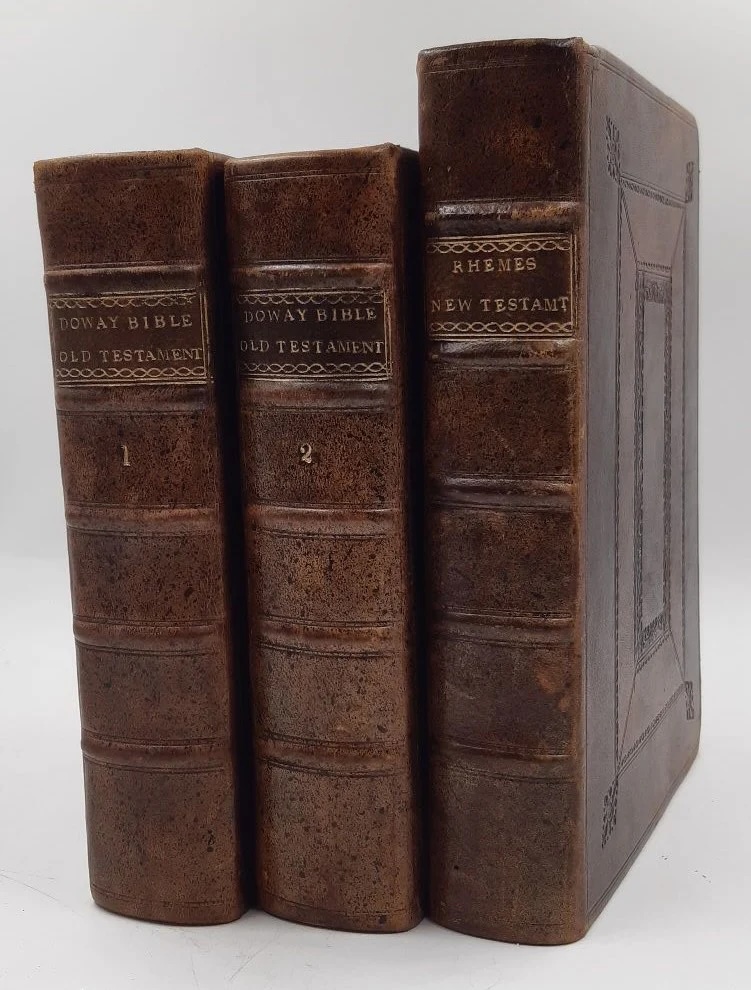

The first item that caught my eye was a first edition Douay-Rheims Bible offered by Voewood Books. The three foxed but otherwise unassuming volumes had been featured in the 2025 catalogue under the headline “Catholics in Exile,” which explained that this edition’s Old Testament and New Testament were translated 30 years apart from each other because it “preceded of one general cause, our poore estate in banishment”—a reference to Elizabethan-era anti-Catholic laws. Its contents being essentially criminal at the time made for an intriguing enough story, but this particular copy also had a unique Jesuit provenance.

The scribbled “Blount” in the front matter indicated that the copy had made a long pilgrimage from a haven of Catholic scholars in Rheims to the estate of the Blount family, most likely smuggled into England by the Jesuit priest Richard Blount while he ministered to Catholics illegally for almost 50 years in the 16th and 17th centuries. A stamp in the book further indicates that its stint as a family heirloom ended when it returned to the hands of Jesuit academics—this time at Stonyhurst College—and eventually into mine when the gentlemen from Voewood Books handed it to me.

It is a heady experience to hold an object that is so much older than you and that will, if the number of its many previous owners is any indication, far outlast you. Yet I was struck by the thought that this was probably the exact, stubborn intention of the men who created it. Banished from England and with a dark future for Catholicism in their sights, the early creators of the Douay-Rheims Bible, like Cardinal William Allen and his colleagues, persisted for 30 years in creating a lasting Catholic tradition that would endure past their exile and a period of political corruption. Voewood Books maintains that this is the exact kind of history and struggle nuance that makes it “all the more attractive” for private collectors.

Anti-Catholic nativism

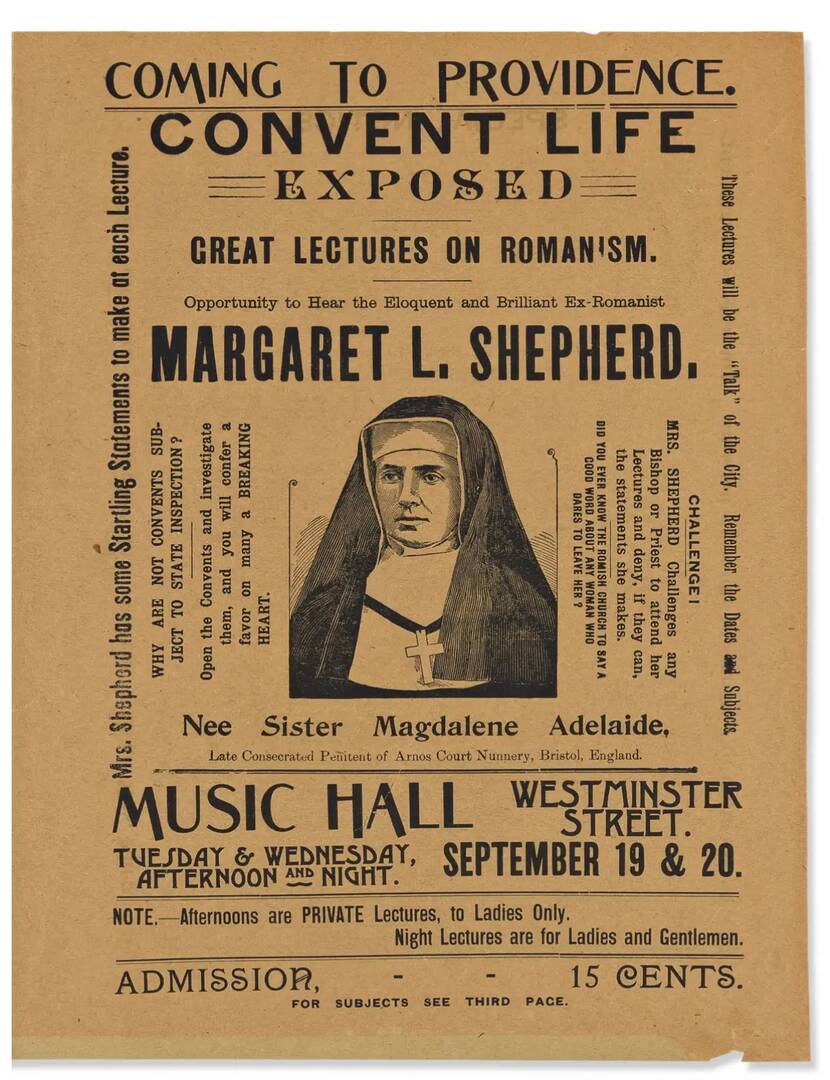

Moving deeper into the fair, the next piece I encountered featured a fake nun with a vendetta against the church. This oversized brochure, pictured left, is a relic of the nativist movement of the 19th century and, per the research of Auger Down Books, features just one of several “nuns” who went on the advertised lecture tours promoting anti-Catholic rhetoric. That much was apparent when I opened the broadside to find claims that “God of Heaven had chosen Mrs. Shepherd”—the alleged former nun—”to strike a deadly blow to the seven-headed hydra of Rome” and how “from a bitter personal experience,” Shepherd found that “Roman Priests are effacing God’s image from souls and are implanting hellish seeds.”

As darkly humorous as these quotations might be, they are based on entirely false claims. It is likely that no one in Shepherd’s audience was aware of this and the commercial aspect of the endeavor (the broadside repeatedly notes that Shepherd’s books are for sale and available for bundling) guaranteed her handsome profits for disseminating anti-Catholic prejudices. The tale of Catholic persecution told here seems to appeal to the same customers who might be interested in the plight of the translators of the Douay-Rheims Bible. The bookseller, whose shop specializes in Americana, had previously acquired and sold a variety of pieces related to anti-Catholic nativist history, and it was clear from this one that Catholic aesthetics were a preoccupation even when they were bound up in anti-Catholicism.

Medieval personalization of prayer

Books of hours were among the most popular items on display at the book fair. Those pops of lapis lazuli, the impressive detail of landscapes no bigger than your palm, entire color palettes contained within a single capital letter made using only methods available over 600 years ago—it was clear why these prayer books are highly sought after by the likes of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

I was taken aback when I flipped the page of one prayer book only to be met with the neat handwriting of a previous owner in the 16th century who had taken advantage of a blank page to transcribe some prayers. These carefully written French verses were directed to St. Genevieve, St. Anne, St. John the Evangelist and of course the Virgin alongside motets in Latin transcribed from other sources.

Various saints are featured in the book alongside histories and prayers, selected according to the preferences of the original publisher. It was heartening to think of fellow Catholics who carried this volume around on a daily basis, ready to say a prayer at the appointed time. Dr. Sandra Hindman, the founder and proprietor of the art gallery and dealership Les Enluminures, noted that antique books were pieces of art unto themselves, though quite distinct from a painting. The art was something you carried around with you, and required the turning of a page. Reading it today replicates the ritual of readers centuries past and gives you a sense of what used to be a human being’s intellectual lifeblood.

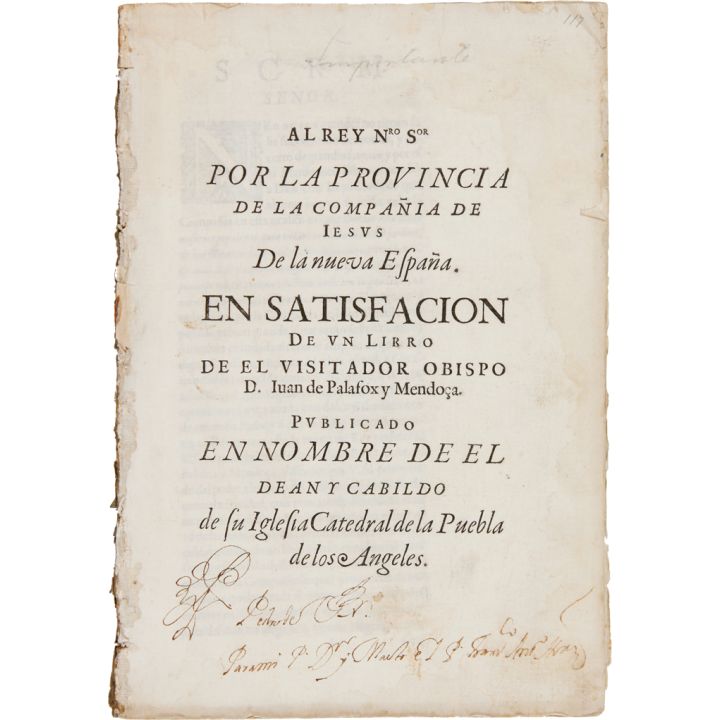

Road to expulsion

Even offerings tucked into the corners of booths yielded historical insights such as papers detailing a feud that foretold the eventual mass expulsion of Jesuits from Europe and its colonies. As the description from William Reece Books indicates, these folios (pictured left) documented the legal filings Jesuit missionaries had placed against the 17th century viceroy of New Spain, which covered vast swaths of North and Central America. The viceroy, Juan de Palafox y Mendoza, a clergyman, sought tithes from Jesuit properties in an act the Jesuits perceived as an attempt to establish the conditions of their potential excommunication.

The Jesuits, typically for the time period, called in political favors to drive Palafox out of New Spain and later to prevent his canonization. Palafox was only recently designated blessed, in 2011. Convenient as the victory must have been, it proved a short-term triumph for the 18th-century Jesuits once their political fortune took a turn for the worse when faced with mass expulsion from Europe, with Palafox’s writings playing a crucial role, particularly in Spain.

The folios were extremely rare, with the first and most intriguing document being one of only three known. The other two are known only from mention of them in records. It is a fascinating primary source document for the legal history of the church, albeit one with an asking price of $12,500.

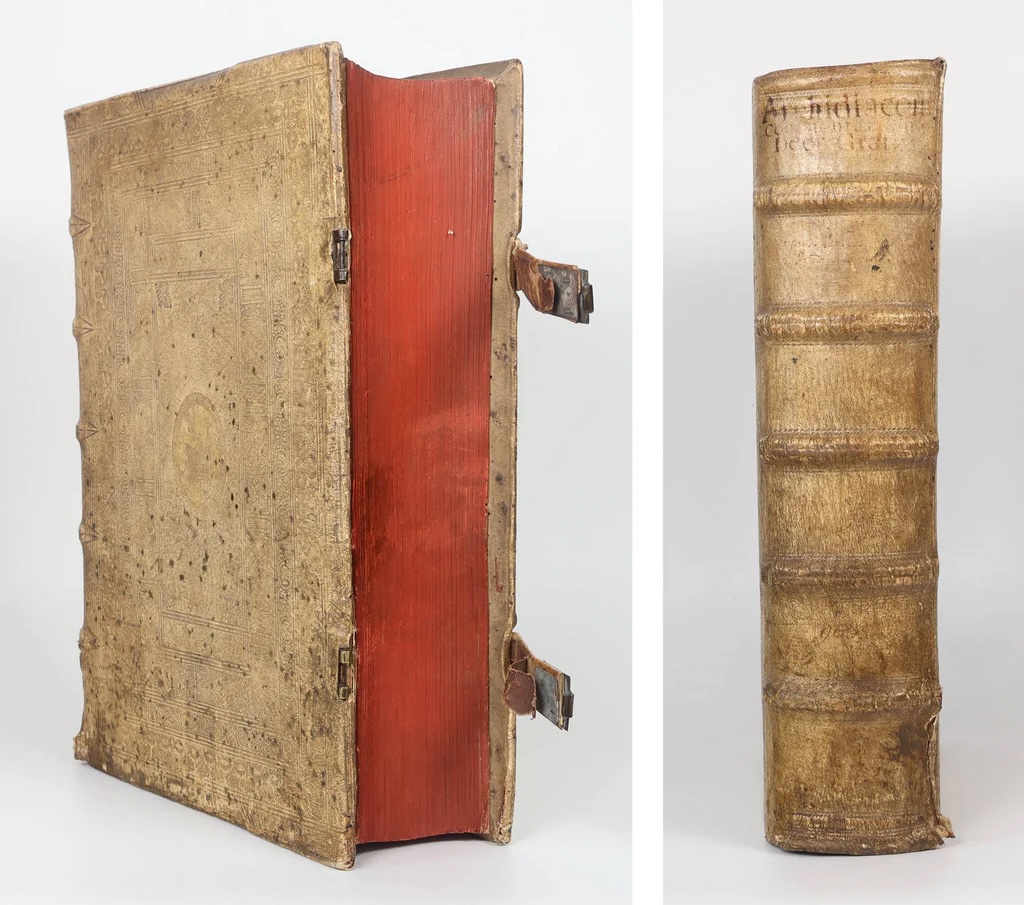

The behemoth

While wandering among the booths, I encountered a behemoth of a book. It is a copy of Guido de Bayso’s commentary on Gratian’s pivotal Decretum that remains in remarkable condition. Of interest is an editor’s letter unique to this edition assuring Cardinal Francesco Todeschini-Piccolomini, the future Pope Pius III, that various errors in previous editions were corrected in this one. What follows is a printing riddled with production errors.

Some of the red and blue guide letters don’t match the corresponding letter the printers placed beneath them, and many are missing entirely. In a charming act of concern for the titanic tome in their possession, however, at least one or two later readers (who also left marginalia on original sin and menstruation) took it upon themselves to correct some of these lettering errors through various crude drawings. These penciled-in corrections, paired with the stiff printed text, make for a unique artifact that reveals early examples of close reading in a theological text.

Such “flaws” are prized among sellers of religious antiques. A Jesuit school’s library stamp, a scribbled-down prayer, a medieval Catholic’s amateur attempt at calligraphy: these are the first details an eager bookseller will highlight for the curious. It reminds you that these relics of previous eras marked both times of Catholic flourishing and times when Catholic sentiment was at a low point. After surviving for centuries and traveling thousands of miles, the book is now here, and you are holding it. It is a reminder that the threads of history and faith can come together in a single object. Others might call this feeling something amorphously spiritual, and they might pay thousands of dollars for it, but to me it offers something more: a sense of God’s lasting presence.