Several years ago I attended the world premier of the opera “John Brown.” Brown was a serious Christian who abhorred slavery and came to believe that it could only be uprooted through force. Was the violent raid he led on the armory at Harper’s Ferry in 1859 justified? The opera, composed and written by Kirke Mechem, doesn’t say. It simply depicts the historical circumstances that led Brown to undertake a signature act of American terrorism and shows us the complexity of the man and his era.

The opera “John Brown” raised powerful and profound questions. I would hope that “The Death of Klinghoffer,” another opera about terrorism, does the same. I haven’t seen it so I can’t comment on its merits as an opera, but it’s been fascinating to follow as a story. Even before its opening at the Metropolitan Opera this week, the opera was intensely controversial, with opponents calling it anti-Semitic and/or sympathetic to terrorists and seeking to prevent it from being staged. Composer John Adams has disputed the charge of anti-Semitism, as has the management of the Metropolitan Opera and the Anti-Defamation League. The ADL brokered an agreement that enabled the Met to go forward with the production but kept the opera house from offering a video simulcast of it. This on the grounds that while the opera itself is not anti-Semitic it could give rise to anti-Semitic acts outside the United States. (Ironically, the ADL is now being accused of anti-Semitism by some of those protesting the opera, as are the general manager and a few other officials of the Metropolitan Opera who are Jewish.)

I regret I won’t be able to see the telecast of “The Death of Klinghoffer” so I can judge the opera for myself, but I’m glad that at least the production went forward. If political pressure keeps artists from treating controversial issues, our society is poorer for it. Most of us have entrenched opinions, but art can touch people in ways political argument cannot. In the 19th century, Uncle Tom’s Cabin changed the way many Americans viewed slavery. A century plus later, I’m probably not the only white American whose perspective on race has been influenced as much by novels as by experience.

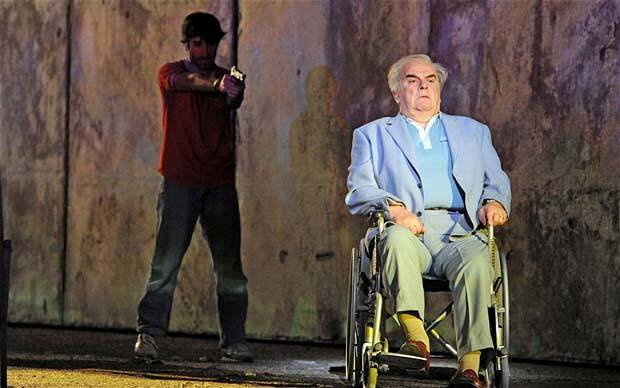

Composed in 1991, “The Death of Klinghoffer” portrays a true incident – the 1985 murder of Leon Klinghoffer, a disabled American Jewish passenger aboard the Achille Lauro cruise ship, by Palestinian terrorists. Those who oppose its performance at the Met contend that by depicting the point of view of not only Klinghoffer and the other passengers on the ship but also the Palestinian terrorists who hijacked it, the opera glorifies terrorism.

To portray a point of view is not to glorify it, of course. This might seem obvious, but is not to the protestors, most of whom haven’t seen the opera they oppose. They’ve been joined by politicians ranging from Rudy Giuliani to Congressman Peter King to former Governor David Paterson. Ideally our politicians would shed light, not more heat, on the issue of terrorism, but as the furor over “Klinghoffer” shows, anything related to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, even a 23-year-old opera, is so hot few politicians are willing to do anything but fan the flames and warm themselves in the reflected glow.

Move beyond that particular conflict, and it’s not much different. Our public discussions of terrorism are steeped in cliché and the language of bad fiction, with “bad guys” and “good guys” going after each other at every turn. Only in imagined works dramatized on stage, television and opera halls, or expressed in novels, is there an acknowledgement that real life is rarely simple. Audiences who see “John Brown” may perceive the abolitionist as a terrorist or as a hero, but the institution of government-supported racial slavery he sought to overturn was surely wicked.

Understanding and addressing terrorism requires clarity, as with other ills. Does “Klinghoffer” bring that to the episode it dramatizes? In addition to the musical demands imposed on every opera, that’s the challenge it faces. As a country, it’s ours too today.