Cambridge, MA. In a New York Times column entitled “So Much Fun. So Irrelevant,” on January 3, Thomas Friedman focused on the importance of the vast advances in global connectivity, and the way what and how we know today is changing the quality of our lives. All of this of course rather well-known by now, but Friedman’s point is to notice how during the current primaries candidates are not talking about US readiness in the field of global knowledge, and no one is pushing them on this, to see what they know. As he comments at the end of the piece, “I just don’t remember any candidate being asked in those really entertaining G.O.P. debates: "How do you think smart cities can become the job engines of the future, and what is your plan to ensure that America has a strategic bandwidth advantage?”

Interconnectivity is a good Catholic principle too, on an interreligious level too, so it seems good at the beginning of the year and on the feast of Epiphany (more on this below) to remember how basic and important interreligious connectivity is for us today, in what should be a necessary part of every serious conversation about Catholic identity today. We are members of a global religious community, and everywhere meeting people of other religions is a feature of our lives. This too should be well-known by now, but there is always the temptation to turn in and ignore the wider world, preoccupied with inside-the-Church issues.

First a familiar point of fact: there is no evidence that religions – altogether, or just others’ religions – are going away. We need to build into our Christian self-consciousness recognition of and comfort with the fact that other religions will continue to flourish around us. They are not going away, not in our life times, and not in this still-new millennium.

Moreover, in a world where religion is increasingly not mandated by political and governmental power, diversity is about us, not just about them. We must observe how conversions happen from as well as to Christianity, that there is a fluid space at the margins wherein people cross back and forth. Some claim complex religious identities, no longer identifying themselves as entirely and solely belonging to one religion. Catechism, RCIA, high school and college theology curricula, spirituality and retreat programs all must take this interconnectedness into account, even if we don't approve of it or sometimes find it lacking in depth, since the very people who come to us and whom we are educating bring complicated religious lives with them. It does no good, too, to hold that people need to learn the basics of the Faith first, and think of other religions later. Priority on the truths of our tradition testifies to an important value of our faith, but there is no purely Christian, pre-diversity “first” that can be worked out before the issues of diversity come to the fore.

Of course, what such things mean is not to be taken for granted. Recognizing global interreligious interconnectivity is not and ought not be labeled a matter of liberal and conservative. Yes, in the interpretation of what global diversity means for the Church, we will bring to bear our conservative and liberal, progressive and reactionary instincts. So too, how we think about basic Christian truths and values will play a role. But it is in no way “liberal” to admit that religious diversity is now a regular dimension of our Christian lives, nor it is a higher "conservative" virtue to deny that diversity is real and enduring.

But there does not need to be a trade-off between commitment and openness. If we are Christian, we need to confess and nurture and live a fundamental and irreversible commitment to Christ. But this commitment is not to be confused with intellectual closed-mindedness, or with an attitude that other religions are merely a problem or merely a drag on Christian commitment.

Friedman points out that we should at least expect of our politicians that they be on top of the issues related to the globalization of knowledge through new technologies, and we should refuse to accept politicians who imagine that intellectual isolationism is possible. We too should expect, as a minimal starting point, that our bishops have some basic knowledge about other religions, and as a starting point, they should be well beyond basic mistakes and stereotypes. For example, we should have only religious leaders who know that Judaism is not merely law, and not merely an old testament that has not evolved since the coming of Christ; Islam is not essentially violent, nor simply a mistake that spoiled the early Church; Hinduism is not mere polytheism nor reducible to the belief that the world is only illusion; Buddhism is not a crude nihilism; native, indigenous traditions are not merely remnants of the religions that existed before history began. To know such things is not an advanced course, and should be a necessary precondition for being a teacher or leader in the church. No bishop, nor parish priest, nor dean at a Catholic college, should get through his or her first year in office without some candid questions and conversations about diversity and its meanings.

But minimal correct knowledge of the other is just a start. Intelligent and attentive Christians must move beyond this minimal literacy-about, to constructive ways of dialogue and of learning from other religions. It would make sense if one of the litmus-test items used to determine advancement in the Church is interreligious sophistication, skill in showing how commitment and openness go together. Ignorance of other religions, ignorant attitudes about their beliefs and practices, a life of keeping the other at a distance, all should be grounds for disqualifying someone from being a bishop, seminary rector, formation director, etc.

Such religious interconnectivity can be a Christian and Catholic virtue that is of service to the world as a whole — an important dimension of Christian mission. The world is going to be religiously diverse for a very very long time, and a contribution we can make — for the Church but also for people in other traditions — is to show how commitment and openness can be kept together.

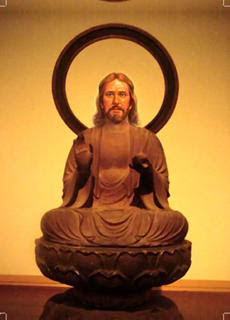

This Sunday, January 8, we celebrate the feast of Epiphany, a very manifest and bold sign that the event of the birth of Jesus was from the start also an event of global significance. The story of the three wise visitors from the East is rightly a key image we connect with the birth of Jesus in Bethlehem, and it is an interreligious moment. It is Jewish, of course, but it is also a matter of the religion of the visitors, something not Jewish, from the East. They come to Jesus freely - and we have to let them return home freely, taking Jesus with them.

Whatever else we discuss in the Church this year, let’s honor this feast by recognizing this key fact about today's world, and by taking seriously the interreligious dimension of every aspect of being Christian, being Catholic today. How each of us does this, how a bishop does it, or a teacher, will vary, but none of us lives in a world where religions do not matter deeply for being-Christian.

Or more simply: make a new year's resolution, learn something in depth about another religion during 2012.

wonderful introduction to a book.I am snowed under with Meissner on Ignatius and Camus but thanks for giving me this brief little snapshot.I agree wholeheartedly with the sentiments expressed.

We are before a mystery, a mystery in flesh for us Christians but nonetheless a mystery.

The basic thought is that the world religions paradigm which identifies constructs such as "Christianity," "Hinduism," "Buddhism," etc. as discrete entities about which one can make meaningful generalizing statements is deeply unnatural for describing what anybody is actually doing when they practice what we have deigned to call their "religions". Possibly the categories are altogether distorting and unhelpful, for instance if there is really no meaningful definition for any of these religions that consistently and coherently differentiates a given religion from analogous systems of belief/practice. But at the very least, aren't the snapshots of the "religions" we teach to students always reflective of the belief/practices of a small, extremely unrepresentative subset of the people claiming to practice the "religion" in question? The concern is that we are valorizing and reinscribing specifically elite constructions of religions at the expense of all others, and in the end persuading people no longer to practice forms of these religions that do not fit the standard textbook descriptions. This is particularly evident in Asia, where a longstanding traditional religious permeability seems to be hardening into discrete groups of "Hindus," "Buddhists," "Taoists," or whatever (as opposed to the situation in the past, when most people would occasionally take advantage of the services provided by religious specialists of each of the religious traditions available in their area in and very few people would self-consciously identify themselves as belonging to a specific "religion" as opposed to some other "religion". These people are the vast majority of religious practitioners throughout history, particularly in Asia, but Catherine Cornille for instance seems to completely write them off as irrelevant to understanding "authentic" religion in her "Many Mansions" when she argues that people must submit totally to elite standards of religious belonging or else belong to no religion at all). Most notably in India non-conforming "Hindu" traditions get Sanskritized and also differentiated from other "religions" for the political advantage of a few, who then use their religious identity to marginalize and oppress others.

Is there a way to promote awareness of religious diversity (surely a laudable goal!) without contributing to the problem of communalism the world religions paradigm has contributed to in Asia?

I am not sure if any of the knots are loosened but it places us with a lot more questions than answers.The one thing I would disagree with absolutely is the idea of the litmus test .Why?Pope Wojtyla did this and it was a disaster.Anybody who disagreed with him was essentially a bad catholic.Anybody who threatened him intellectually was a heretic.

This lead to a very impoverished episcopacy, basically yes men with very little pastoral experience.Your litmus test is the same thing.Anybody who is not in the mold of an inter-religious person should not advance.

In Peru there are about 12 non-catholics and so a Bishop would only have to know how to follow christ and not know the 99 names of Allah to get on.The litmus test would be ridiculous or in most parts of Chile ,a knowledge of other Christian groups would be helpful.

If we advance in knowledge of Jesus Christ then we will come to have an openness to the Other.Catholic ghettos are built by people more interested in identity than Jesus.

That said ,I have to read this article again.

Thanks

A definition of Anatheism from the book: "It is a movement - not a state - that refuses absolute talk about the absolute, negative or positive; for it acknowledges that the absolute can never be understood absolutely by any single person or religion ..."