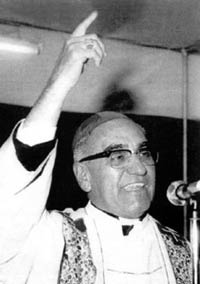

I have been thinking about the martyrs in the church’s recent history—among them, Martin Luther King Jr., the Ursuline missionaries, Jesuits and companions in El Salvador, Dorothy Stang, Oscar Romero—those people who you might say carried within them a bit of crazy, a lot of courage and a heaping portion of love.

I have been thinking about the martyrs in the church’s recent history—among them, Martin Luther King Jr., the Ursuline missionaries, Jesuits and companions in El Salvador, Dorothy Stang, Oscar Romero—those people who you might say carried within them a bit of crazy, a lot of courage and a heaping portion of love.

They were human, saintly perhaps, but human nonetheless. They had families and personal histories, character flaws and insecurities just as surely as we do. They were, at times, uncertain and frightened, just as we sometimes are.

And yet they persisted in seeking and speaking the truth, even when it meant facing hard realities, becoming involved in complex situations, being unpopular among people of stature; even when unhinging their hearts and mouths meant placing their lives in danger. They were not guaranteed pleasant outcomes in exchange for boldly bearing witness and on some level they all knew it. And yet they each seemed to have reached a tipping point of sorts, after which there was no equivocation and no question that the injustice in their midst was a direct affront to God’s dream, and they placed the full force of their gifts and capacities in the service of restoring that dream.

A reading of The Violence of Love, a collection of excerpts from Romero’s homilies from 1977 through his death in 1980, sheds some light into the quality of courage and conviction that impelled Romero onward. What is evident is that, over a period of time, he moved beyond the fear and caution that obscured his view of what was going on around him and came to see the situation so clearly that he could not remain silent. In Romero’s case, this was the torture and killing of thousands of Salvadorans at the hands of a repressive and corrupt dictatorship. Of course, being in possession of human free will, he could have looked the other way. It seems, however, that it eventually became more painful to deny the truth than to risk it. Life and love demanded action and Romero obliged.

What makes Romero’s stance truly radical and truly Christian is his unwavering focus on love—love that could not be limited to the oppressed majority that he stood with, but which also sought the good of the brutal individuals who were terrorizing and murdering. He never ceased to desire their conversion and their salvation and he addressed them directly in many of his radio broadcast homilies. He also recognized that without “liv(ing) a conversion” in his own heart, he would become “feeble, revolutionary, passing, violent” (p. 1). His fidelity to the principle and practice of love was grounded in prayer and modeled after Christ, whose self-gift was boundless and poured out for all with no exceptions. It flowed from the belief that God, the creator of the tortured and the torturers alike, consists of love and that we are created to reflect and channel God. The decision to allow love to come to fullness in his own life, not to suppress it when it became large and unruly, led him beyond the fear of death and rejection into a “deep joy of spirit in being at peace with God and with our brothers and sisters” (p. 8).

Of course, thinking about great (and fully human) followers of Christ challenges us to look inward. I think the extreme examples that Romero and other martyrs provide are so compelling and so disquieting because they are not unrelated to our own journeys of faith. We are not immune from the tipping point effect that “unhinged” Romero and the others. In fact, our faith asks us to get there, to tip out of ourselves and into God. It calls us to seek to see the world as God does, and that can be hard. That is why it is tempting to avoid honest and sustained prayer—contemplation opens us to see things as they truly are, and that can be deeply unsettling. Invariably, life and love demand action of us.

Perhaps remembering that we are daily awash in God’s unconditional, illogical, unstoppable love will provide a nudge beyond our own binding fear and will embolden us to oblige the call to bear witness in our own lives.

Catherine Kirwan-Avila

There is indeed much good being done after the example of Romero and the Jesuit Martyrs. Little of it is coming from the chanceries.