The Witness of Suffering

Slaves in the Greco-Roman world were sometimes treated with kindness, but this was dependent upon the whims of masters, not legally required. Even domestic slaves, as mentioned in 1 Peter, were vulnerable to the demands of their masters, and 1 Pt 2:18 asks that they “accept the authority” of masters “with all deference, not only those who are kind and gentle but also those who are harsh.” Possessing no right to the integrity of their own bodies, such a request could entail all forms of abuse, whether sexual, physical or other.

It is difficult in the 21st century to read the first-century advice that “if you endure when you are beaten for doing wrong, what credit is that? But if you endure when you do right and suffer for it, you have God’s approval.” This sort of advice seems to require a mute acceptance of cruelty and tacitly reward those who perpetrate it. As we have become more aware of human trafficking today, a form of slavery that flourishes all around us, what sort of message does this passage send?

It is important to remember that in the first century, slavery was a legal institution, and manumission was dependent upon individual owners. People who helped slaves escape were accountable to the law, and runaway slaves would be subject to bloody (and legal) retribution. Since the early church was small in number and politically insignificant, the early Christian response was to encourage slaves by offering Jesus’ own unjust suffering as “an example, so that you should follow in his steps.”

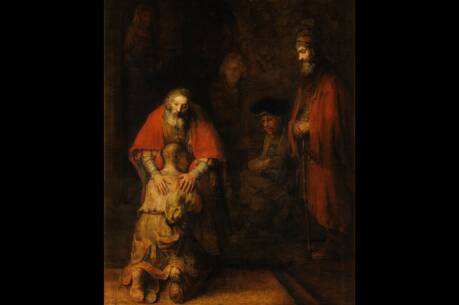

1 Pt 2:22–24, which some scholars believe was part of an early Christian hymn, offers a meditation on Jesus’ suffering in the context of Is 53:4–12, a Suffering Servant song. The genuine suffering of slaves in the first century is not denied, but aligned with Jesus’ own experience. In fact, all who suffer unjustly, even in the 21st century, can identify with Jesus as the one who “when he was abused, he did not return abuse...but he entrusted himself to the one who judges justly.” Suffering is now given spiritual meaning, so that the effects of Christ’s own suffering are applied to those who suffer in the body of Christ.

But is there a danger here that we will watch silently from the sidelines as the weak and abused suffer? It cannot mean that. St. John Chrysostom, in his treatise “On Vainglory” (No. 69), instructed Christian boys to accept misfortune when it occurred, but “never to allow another to undergo this.” Wherever suffering and injustice occur, it is our task to bring it to an end through our witness. Yet there are times when we or others might suffer unjustly, and despite all attempts to bring it to an end, we must endure it. It is here that the model of Jesus helps us understand that as Jesus was vindicated through his innocent suffering, so, too, through his suffering he has healed us and will heal us from all our wounds.

I do not want to suffer. I do not want those I care for to suffer. Really, I do not want anyone to suffer, but when we do, it is important to know that the Good Shepherd knows our suffering. 1 Peter says that we “were going astray like sheep, but now you have returned to the shepherd and guardian of your souls.” Is 53:6 makes it clear, in fact, that the source of the Good Shepherd’s suffering emerges because the sheep have gone astray and “the Lord has laid on him the iniquity of us all.”

Jesus’ innocent suffering can help us make sense of our own suffering and give it spiritual purpose as we work to end it. His suffering also allows us to align ourselves with those who today are enslaved, physically abused, bullied or who are vulnerable for myriad other reasons. As we ourselves endure suffering and act to bring the suffering of others to an end, it is important to recognize that the goal of the Good Shepherd is not to create suffering, but to bring it to an end. We bear witness that the Good Shepherd has come that we “may have life, and have it abundantly” and to bring us all safely into the sheepfold.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “The Witness of Suffering,” in the April 28-May 5, 2014, issue.