Even conservative voters support federal aid to their communities when the program predates the Barack Obama administration. And taking the nomination process away from political parties may lead to more kinda-sorta moderates in Congress.

Those are two interpretations of the upset in a special congressional election in Louisiana on Saturday, when conservative Republican Vance McAllister beat even more conservative Republican Neil Riser in a run-off to represent the 5th District, which covers most of the northern part of the state. A major campaign issue was the expansion of Medicaid to help cover what New Orleans’ Advocate newspaper reports as “the 20 percent or so of district residents without health insurance.”

McAllister was for the expansion; Riser opposed it, as does Republican Gov. Bobby Jindal, because it’s a component of the Affordable Care Act (“Obamacare”) and will eventually require some funding from the state (though the feds pay for the entire expansion for the first three years and 90 percent of it afterward). “A vote for McAllister is a vote for Obamacare” was the tagline for one of Riser’s campaign commercials—which may be still viewable here, though it’s been taken down from YouTube.

Josh Marshall flags McAllister’s 20-point win as a “counter narrative” to stories about the ACA as a political disaster: “Riser hit McAllister hard as a crypto-supporter of Obamacare and this was seen going into last night’s vote as the defining issue in the race. And McAllister won handily.” Add the defeat of a Tea Party candidate in a Republican congressional primary in Alabama and the loss of anti-Obamacare crusader Ken Cuccinelli in Virginia’s gubernatorial race, both of which occurred earlier this month, and you have a nice triptych to illustrate that it’s possible to run too far to the right even in red states.

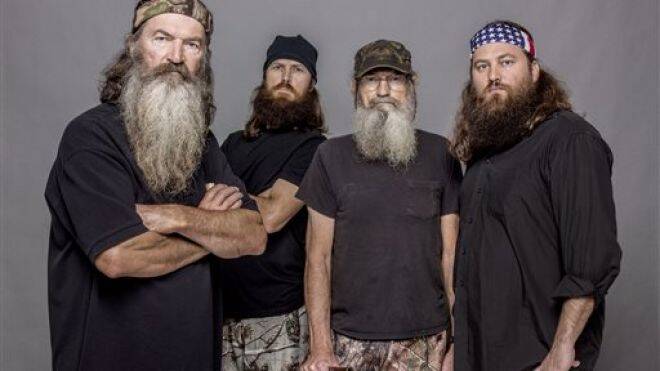

But let’s not get carried away. McAllister did not run as a supporter of Obamacare or a moderate. See his own website: “As our conservative voice, Vance will stand strong for the 2nd Amendment, the unborn, fight to repeal ObamaCare, and reduce the size of government.” The Advocate emphasized his outsider status in reporting the result. (Lead sentence: “Rookie Vance McAllister says he’s never visited Washington, D.C., but now he has a job in the nation’s capital.”) The newspaper also notes that McAllister, the owner of various local businesses, beat Riser, a state senator, with the endorsement of stars from the popular reality-TV series Duck Dynasty, which is filmed in the district. It’s unusual for the outsider in a Republican primary to be considered the (slightly) more pragmatic candidate, so this may just be a case of voters opting a new face over Tea Party orthodoxy when forced to make a choice. In general, the implementation of Obamacare is not going to be helped by outsiders winning Republican primaries.

Another unusual factor in the election is that Democratic voters had to choose between two Republican candidates, since Louisiana uses the “jungle primary” system in which the top two vote-getters in the primary advance to the general election regardless of party affiliation. In theory, this can produce more moderate, less partisan elected officials. Last year Salon’s Steve Kornacki wrote about California’s adoption of the system in a piece called “The Cure for the Tea Party?” Kornacki hoped that “In a solidly Republican district, for instance, Democratic voters could end up as the decisive bloc in a race between a moderate and conservative Republican.” Today NPR’s Mara Liasson interviewed a proponent who said, “half of California’s Republican members in Congress broke with the Tea Party on the shutdown. In Washington state, where non-partisan primaries have been in place since 2008, all of the Republican members of Congress voted against the shutdown.”

If moderation is the goal, the non-partisan primary system worked, if almost imperceptively, in Louisiana’s 5th. McAllister was especially strong in more urban parishes where Mitt Romney merely crushed Barack Obama last year, as opposed to grinding him into a fine dust, suggesting that Democratic voters were responsible for his landslide margin if not the win itself.

Still, this is a case where the non-partisan system resulted in a Republican congressman who may vote with his party 95 percent of the time as opposed to 98 percent. A study by three political scientists, who posted in the Monkey Cage blog, suggests that the system may tip the odds toward relatively moderate candidates in general elections featuring two members of the same party, but it does not to much to advance centrist candidates in districts where both parties are competitive. The authors looked at the 2012 primary results in California and concluded that running toward the center didn’t help candidates advance to the general election. They speculate on the reason:

While voters are generally quite moderate and were willing to cast crossover votes (roughly 12% of our participants who voted for a major party candidate did so), they largely failed to discern ideological differences between extreme and moderate candidates of the same party, particularly if they were challengers.

For most voters, party affiliation is the biggest signal of a candidate’s views. When candidates from the same party compete, it takes more time and effort to distinguish them—and moderates may have a disadvantage in getting their message out because it’s harder for them to raise out-of-district money from liberal and conservative activists.

Some of the comments to the Monkey Cage post dispute the idea that moderation should be the goal of a non-partisan system anyway. (From Chad Peace: “There is a fundamental misconception that the non-partisan primary is about moderation. It’s not. It’s about being accountable to the electorate. A ‘moderate’ by statistical analysis has little to do with accountability.”) And McAllister may have won in Louisiana not because he’s perceived as more moderate but because Democrats and enough Republicans preferred a newcomer to a state legislator who’s probably taken some unpopular votes in support of his party’s leadership.

So was McAllister’s win due to a thirst for moderation or a hunger for Duck Dynasty populism? Pick your spin.

Photo of Duck Dynasty cast from A&E.