We’ve just had two months in which political journalists have implied that millions fled the Republican Party (because of the government shutdown) and then millions fled the Democratic Party (because of Obamacare). So this Thanksgiving is a great time to conduct a survey. Ask your relatives and friends if they’ve even changed partisan loyalties and why. This will not require as much interrogation as you might think; the quadrennial focus on “swing” voters notwithstanding, few Americans bounce back and forth between the Democratic and Republican parties.

If my experience is any indication, you will find that most adults have stuck with one party for many years and that those who switched mostly did so for personal reasons. Some might have moved to the left because of a child in an underfinanced public school, or the inability to get health insurance because of a pre-existing condition, or a relationship with a gay person who wants to get married. Others may have moved to the right because they’re small-business owners exasperated with regulations, or their tax burdens has increased, or their neighborhoods have high crime rates. But I rarely talk to anyone who’s gone from hating to loving a party (or vice versa) because of the way a president or congressional leaders have handled a crisis.

Sure, a long pattern of behavior—the Republicans repeatedly shutting down the government or the Democrats continually changing the rules on health care—can change perceptions of a political party. But that change occurs over months and years, not during the few days of an exciting story in Washington.

Time TV critic James Poniewozik gets at the media’s habit of overstating political damage when he mocks the idea of the Affordable Care Act as “Obama’s Katrina,” referring to the hurricane that devastated New Orleans and supposedly turned the electorate against George W. Bush. Poniewozik notes that this is about the 12th crisis that has been given that label:

At conservative site Breitbart.com, days before the 2012 election, Hurricane Sandy was “Obama’s Katrina.” After tornadoes devastated the Midwest, commentators (including Katrina’s Michael “Heckuva Job” Brown) likened the disaster to “Obama’s Katrina,” criticizing the President for an overseas trip. Sequestration has been Obama’s Katrina. The New Republic dubbed the 2011 debt ceiling crisis Obama’s Katrina. (But, fair’s fair, also “Boehner’s Katrina.” Everyone gets a Katrina!) Earlier this year, conservative Washington Post blogger Jennifer Rubin wrote that, “In a way, the NSA intelligence gathering is Obama’s Katrina.” Sure! In a way, what isn’t?

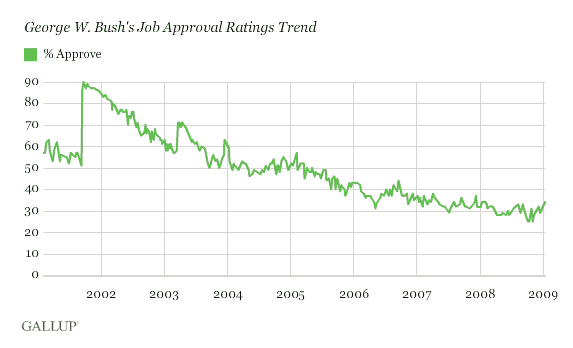

What makes this knee-jerk response even sillier is that “Bush’s Katrina” was not the political disaster it’s made out to be. Ezra Klein posts the Gallup job approval ratings for Bush, which show a gradual decline after 9/11 (and through the war in Iraq) but no long-lasting change attributable to his handling of Katrina:

In early 2005, Bush's approval ratings were above 50 percent. His slide began mid-year. By July 28, 2005—so, about a month before Katrina—Bush's approval rating was down to 44 percent. On Aug. 25—so, during Katrina—it was 40 percent. On Sept. 8, it was back to 46 percent. On Sept. 28, it was still 46 percent.

We like to read about “game changers,” like the presidential debate that was supposed to kill Obama’s chances at getting re-elected, or the “47 percent” speech that was supposed to doom Mitt Romney to a double-digit defeat, but public opinion in this large and diverse nation just doesn’t move that quickly.

Political scientist David Runciman takes a longer view, even as he criticizes democracies for not doing so in The Confidence Trap: A History of Democracy in Crisis from World War I to the Present (from the book’s website: “democracies are good at recovering from emergencies but bad at avoiding them.”) In an interview with the Boston Review’s Nausicaa Renner, he suggests that the scandals obsessed over by pollsters are a distraction—and that the most covered political events of all, elections, aren’t the game changers we assume them to be:

Democracies are very bad at distinguishing symptoms and causes. That’s one reason why we always seem to feel like we are in a crisis: it’s tempting to treat every democratic dislocation as evidence of some impending disaster. One consequence of this is that democracies tend to get preoccupied with scandals, which are often taken as evidence of some wider failure of democracy. But scandals are usually a distraction rather than a vehicle of transformation: they allow people to let off steam without threatening the basis of democracy itself. At the time Watergate looked like a calamity for American democracy. In hindsight it looks like it was one of the diversions that helped American democracy to get through the 1970s intact. Watergate was not what produced systemic change.

Another feature of this is our tendency to inflate the significance of elections. We usually see them as turning points when in fact they are often evidence of something having already turned. The shift to a new economic order in the US began during the Carter administration. The election of Reagan was a symptom not a cause of the coming ascendancy of Wall Street. Equally, some elections that look profoundly significant at the time turn out to be less so. Obama’s election might be one of those. The symbolic significance is hard to overstate. But the promised change in how America governs itself hasn’t happened. Nineteen-thirty-two was a rare instance of an election that seemed as important at the time as it turned out to be in the long run.

Could the 2016 presidential election already be decided? And will the new president be behind the curve of political change even as he or she takes the oath of office?

Write down your survey results this Thanksgiving. You’ll want to know if you get different results in four years.