The life of Raymond Hunthausen, the activist archbishop

John McCoy, an excellent writer, tells an insider’s account of the public humiliation of Archbishop Raymond Hunthausen of Seattle. I met Hunthausen on a number of occasions. I always came away with the image of a humble, deeply pastoral and collegial bishop. He was one of my heroes. Bishop William McManus of Fort Wayne told Seattle’s Msgr. Michael Ryan: “Stay with this man and continue to back him. The American hierarchy has produced very few great men. He is one of them!”

McCoy, a former reporter for The Seattle Post-Intelligencer and director of public affairs for the Archdiocese of Seattle (in Hunthausen’s last years and also under Hunthausen’s successor), gathered copious interviews and notes on Hunthausen’s pastoral presence as bishop and on the Roman investigation under Cardinal Ratzinger and Archbishop Pio Laghi, the Vatican’s ambassador to the United States. He then let his proposed book on Hunthausen lie fallow in reams of notes on his computer for many years.

Finally, the person of Pope Francis led him to complete his biography. As he says of Francis: “He reminds me in many ways of Hunthausen. He’s humble, kind, compassionate, plain-spoken and unpretentious. He has a Vatican II vision of the church, of a church that is inclusive, loving, transformative, of a church with a heart for the poor and the oppressed.” The Vatican seemed unimpressed that, under Hunthausen’s leadership, Seattle exceeded the national average on Mass attendance, adult conversions to the church and monetary contributions by some 20 percent.

Born in Anaconda, Mont., Hunthausen became a priest of the diocese of Helena, a faculty member, coach and, at the young age of 35, president of Carroll College in Helena. At the age of 41, Hunthausen was chosen to be the bishop of Helena in 1962. He is the only living bishop to have attended all the sessions of Vatican II, which left a deep impression on him. Even as a seminarian, Hunthausen had been horrified by our dropping atomic bombs on Japan. He puzzled over why we couldn’t have warned the Japanese or dropped the bomb in the Pacific to show its potential devastation. Why, he wondered, did we have to drop it on people? At the council, again he pondered the moral evil of nuclear weapons. The pursuit of Hunthausen mainly stemmed from his opposition to the Trident submarine nuclear weapons stored in the Seattle area.

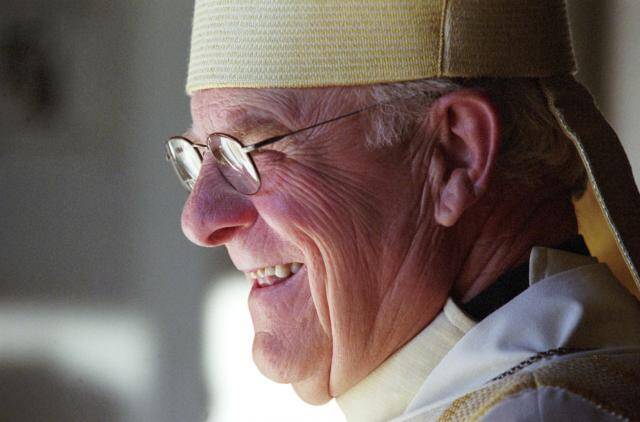

Installed as Archbishop of Seattle on May 22, 1975, Hunthausen chose not St. James Cathedral for the ceremony but the large Seattle Center Arena, where all could attend. Over 5,000 people did so, including Protestant and Jewish leaders. Hunthausen wore a simple white alb and a white cloth miter without adornment. His crozier was a smooth mahogany stick, void of decoration. He set aside his predecessor’s crozier, richly ornamented in gold and silver. He strongly supported women in the church, stressing affirmative action, equal access to diocesan jobs and the removal of sexist language. He championed a priests’ senate. When he attended ecumenical breakfasts and was asked by a Protestant what to call him, since they addressed his predecessor as “Archbishop,” he responded: “I also called him that. You can call me ‘Ray.’” Hunthausen was pro-life and adhered to “a consistent ethic of life.’ In 1980 he persuaded his fellow Washington State bishops to issue a letter, “The Morality of Being a Single-Issue Person,” against those who made abortion a single litmus test for all voting. It said: “A Catholic Church which thinks in terms of only one issue has given up its birthright.”

Beginning in the late 1970s Hunthausen began to speak out and protest against the buildup of nuclear weapons, especially the Trident submarine, harbored near Seattle. He showed up at a protest in 1978 but stated, “I’m here out of my own personal conviction. Not here as the archbishop.” Later, as the Reagan administration built up the nuclear arsenal, Hunthausen publicly stated that he was withholding his taxes and giving them to charity “in resistance to nuclear murder and suicide.”

Unfortunately for Hunthausen, a kind of entente cordial grew between the Reagan administration and the Vatican. Reagan recognized the Vatican diplomatically and gave information to Vatican officials about the Communist bloc. Many in the Reagan administration (especially Catholics, including Reagan’s secretary of the navy, secretary of state, director of the C.I.A., and national security advisor) asked Cardinal Ratzinger to make an example of one of the U.S. bishops who was anti-war. The Vatican sent Cardinal James Hickey of Washington, D.C., as an apostolic visitor. Hunthausen was accused of alleged liturgical abuses, inability to enforce church law, laxity in allowing annulments to marriages, being soft on abortion and being too lenient toward homosexuals (the diocese had allowed a Dignity Mass in the cathedral).

But in a visit to Cardinal Sebastiano Baggio of the Congregation of Bishops, Baggio told Hunthausen he suspected the visitation “stemmed from his involvement in the arms race question.” Later, Hickey told an old friend in Seattle, the Rev. Larry Reilly: “Well, I guess we both know why I’m really here.” Reilly answered: “Yes, you’re here because of Ronald Reagan and the Archbishop’s position on nuclear disarmament.” “That’s right, that’s right Larry,” was Hickey’s response. The Vatican’s reaction was to appoint an auxiliary bishop with special faculties, Donald Wuerl. Hunthausen sought the advice of the Rev. James Coriden, the best canon lawyer in the United States, who told him he did not know what to advise because the Vatican seemed to be making up the rules as it went along. Bishop Wuerl gained final authority over six areas: liturgy, marriage, clergy and seminarians, ex-priests and any issues related to health care and homosexuals. In effect, the archbishop was symbolically stripped of office.

It was an unworkable arrangement (which even Wuerl later admitted). A sign that the main cause was not pastoral failures but the peace activities was that the only other bishop to get an auxiliary with special faculties was Bishop Walter Sullivan of Richmond, Va., who, as bishop advisor to Pax Christi, was also a peace activist. The 17 bishops of the Northwest (except Archbishop William Leveda of Portland) sent a letter to Pope John Paul II praising Hunthausen and asking that he return Seattle to normal ecclesial governance. The American bishops in 1986 took up the case. A three-member commission suggested a new coadjutor, Thomas Murphy of Billings, Mont., who would have responsibility but not ultimate pastoral decision on the areas assigned to Wuerl. Both worked hard at this task, but it is unworkable to have, equivalently, what is, in effect, two archbishops in one diocese.

Notably, Hunthausen was one of the first archbishops to deal forthrightly with the clergy abuse issue. He turned over priest pedophiles to the law and said, in a letter to all his priests sent in 1988, that he would name pedophile priests and asked the priests to follow procedures if a victim came forward. Jason Berry, the first journalist to break the priest pedophile story, said, “Hunthausen was the first archbishop to deal with this problem publicly. The fact that Hunthausen spoke out and was so forthright—you cannot overestimate that!”

Hunthausen was investigated, punished and humiliated. He had no official legal representation, no right of appeal, no due process or access to the report of the allegations made against him to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

Hunthausen retired in 1991 when he was 70. He returned to Montana and has said, “Francis is doing the things I tried to do!” This stellar biography shows a truly courageous and holy man but also deeply unjust and humiliating actions by some church officials.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “Activist in the Chancery,” in the October 5, 2015, issue.