Dr. Karl van Bibber is professor and chairman of the Department of Nuclear Engineering at the University of California, Berkeley. A nuclear physicist specializing in particle astrophysics and cosmology among other areas, he holds a Ph.D. in physics and a B.S. in physics and mathematics from Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He holds numerous professional honors, memberships and fellowships in the scientific community, has been awarded one patent and has published more than 100 peer-reviewed articles. Dr. van Bibber is also a practicing Catholic.

Dr. van Bibber is editor of the recent book The Atom of the Universe: The Life and Work of Georges Lemaître (Copernicus Center Press), an English translation by Luc Ampleman of Dominique Lambert’s definitive biography Un Atome d'Univers. This work is the product of eight years of collaboration between Professor Lambert, Dr. van Bibber, publishers and the translator.

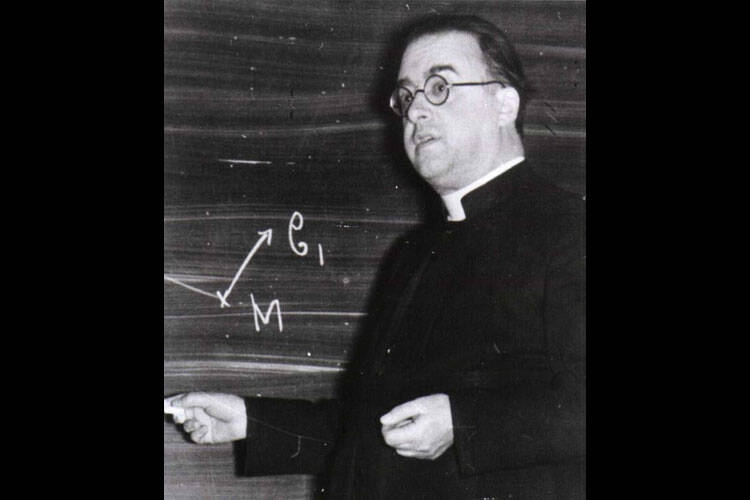

On May 20, I interviewed Dr. van Bibber by email about his work and Monsignor Lemaître, the father of the Big Bang theory.

How did the project of this biography come about?

The book itself traces back to a conference at University of Louvain in 1994 marking the centenary of Lemaître’s birth, where my colleague Dominique Lambert of the University of Namur was invited to speak. His research in preparation for the conference unearthed new archives and fresh details about Lemaître’s life, and captivated by the figure of the priest-scientist that emerged, he embarked on the original version Un Atome d'Univers, which appeared in 1999.

The translation was conceived during a stint in Brussels where I was serving on a scientific advisory panel to the European Commission, I think in 2007. There I met Professor Lambert; we had lunch and having mentioned that I had greatly enjoyed his biography, ventured that a translation would be well received in the English-speaking world, an idea he was immediately enthusiastic with. (Somewhere between English and French, ‘suggestion’ was interpreted as ‘collaboration,’ so here we are!)

The project went slowly at first, but after finding the right publisher and translator, the work took only three years or so, on a nights-and-weekends basis. Being a scientific as well a personal biography of Lemaître, the translation and editing of the technical aspects took the most time and attention.

Who is your audience for this book?

The book represents the fruition of two decades of Dominique Lambert’s scholarship, who interviewed hundreds of colleagues, friends and family members of Lemaître, sifted through all the library collections of his manuscripts, and amassed a vast archive of his personal notes, working papers, correspondence, etc. I initially challenged Dominique’s conviction on his exhaustive footnotes and citations in the book, but it gradually became clear to me that this biography would first and foremost represent a primary resource for all future historians of Lemaître. That having been said, we made great efforts to make it accessible and colloquial for the general reader interested in the history of modern cosmology, histories of Catholic scientists, etc., and I think it succeeds in both roles.

What can you tell us about Monsignor Georges Lemaître as a person, a priest and a scientist?

Lemaître was an absolutely remarkable person, and in some ways still a bit of an enigma, at least to me. He had concluded around nine years of age that he should become a priest, but that project was deferred to 1923 due to the First World War, where he served as a non-commissioned artillery officer, and his engineering studies at Louvain.

Subsequently finding that engineering was much less interesting than the ‘new physics’ and particularly Einstein’s General Relativity (1915), he was awarded a fellowship from the Committee for the Relief of Belgium, under the auspices of the American Educational Foundation, to study a year abroad with Sir Arthur Eddington in Cambridge, one of the leading astronomers in the world. With Eddington’s encouragement, he applied for and won a second fellowship to study at MIT, where for his thesis research he discovered a solution to Einstein’s equations describing an expanding isotropic matter-filled universe.

In addition to being one of the great figures of 20th-century cosmology, Lemaître was a jovial and congenial figure, a man of profound humility and practical wisdom. He was greatly beloved by his students, in spite of his legendary absent-mindedness and chaotic lecture style. He was the target of affectionate roasting in the Revue, the engineering students’ annual variety show, featuring in skits, cartoons and doggerel, all of which he took good-naturedly.

For all his scientific preoccupations, however, he was thoroughly committed to his priestly vocation. He was a member of the first cohort of a new order founded by the eminent Cardinal Désiré-Joseph Mercier, Les Amis de Jésus, that perhaps might best be described as a company of free-lance academic priests. As his own apostolate Lemaître took a special interest in the Chinese students who were studying in Belgium during the 1920s, establishing a residence for them and serving as their chaplain. He was exemplary priest in every way, and never omitted his yearly 10-day closed retreat, although his retreat journals reveal a stream of consciousness, intertwining equations of his current research interests with ascetical considerations. I hope someday we would see the cause of his beatification and canonization being put forward.

How did the scientific community react to Lemaître, a Catholic priest, presenting his theories to the world?

It is important to appreciate what Lemaître had done, in discovering a solution to Einstein’s equations describing an expanding universe; he had provided the key to resolving a conundrum that had vexed not only Einstein, but Newton himself going back more than two centuries earlier: namely, how to explain the stability of a static universe under the influence of gravity, a purely attractive force. The upshot of Lemaître’s solution is that the universe need not be static, and if not, the issue of the universe’s stability is moot.

The Solvay Conference of 1927 marked the first public presentation of the theory, and oddly Einstein found it appalling, good mathematics perhaps, but poor physical intuition. Two years later, with Hubble’s definitive data on the correlation of recession velocity with distance in a survey of the most distant galaxies that could be observed back then, Einstein embraced Lemaître’s theory, and the two later went off arm-in-arm on a lecture tour of the United States.

Nevertheless, the implications of the theory, that the observable universe evolved from a singularity, and that there was a first moment in time, was received with ambivalence and even discomfort in the scientific community, clearly aggravated by the fact that Lemaître, as was the practice for all priests then, wore his clerics all the time, including at scientific meetings; he made no attempt to dissemble his affiliation. Curiously the term “Big Bang” was first applied disparagingly by one of his contenders and detractors, Fred Hoyle.

In addition to being one of the great figures of 20th-century cosmology, Lemaître was a jovial and congenial figure, a man of profound humility and practical wisdom.

What is noteworthy in all this is that Lemaître clearly distinguished in his mind the moment of creation of the universe ex nihilo, from its subsequent expansion; his work as a mathematical physicist and cosmologist solely concerned the latter, and nothing of the former. Ironically then, a purely scientific theory that was proposed by a religious was rejected as a religious agenda by scientists; they were clearly working at cross-purposes.

Why did Monsignor Lemaître seem to lose interest in cosmology so shortly after the triumph of the Big Bang?

By the mid-20th century, progress in cosmology was increasingly bound up with parallel developments in nuclear physics, a topic that unfortunately held little interest for Lemaître. Rather than losing interest in cosmology, it would probably be more accurate to say that he had relegated himself to diminishing relevance in the field. The prime example of the fruitful intersection of cosmology and sub-atomic physics was the work of Alpher, Herman and Gamow in the late 1940s who asked, if we took the Big Bang hypothesis seriously, what would be its physical consequences today? Two profound predictions that resulted were the relative abundance of primordial light elements observed in the universe today, and more significantly, the prediction of the Cosmic Microwave Background, the relic radiation from the Big Bang, ultimately discovered by Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson of Bell Labs in 1965, a year before Lemaître’s death.

Naturally, he was delighted that the smoking gun of the Big Bang had at last been produced, but the Cosmic Microwave Background totally blindsided him; he was convinced that the evidence would be found to be high energy cosmic rays from the disintegration of his “primeval atom,” a notion that was quaint even then in scientific circles.

So what did he do after the initial acclaim of the Big Bang theory?

He got absorbed in classical mechanic’s problems of long tradition, celestial dynamics, etc., and the mathematics it inspired; he was a first-class mathematician as much as a cosmologist. He was also a computing junkie, and set up a numerical calculation lab at Louvain with all the cutting-edge calculators of their time, analog machines such as the Bush differential analyzer, electromechanical machines such as the Mercedes and a vacuum tube Burroughs that was the cat’s pajamas in the late 1950s. And he had his army of students cranking on these machines around the clock calculating galaxy formation and orbits of cosmic rays. You know the type that loves electronic gadgets and building their own computers; he’d fit right in today.

Apart from his scientific pursuits, he had also been appointed by Pope Pius XI in 1936 as an inaugural member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, with Edoardo Gemelli as its first president, a position that Lemaître himself would later assume. Probably his most unusual assignment was his being named by Pope Paul VI to a commission to advise him on the issue of artificial contraception, a request that one can only imagine would leave any cosmologist completely flummoxed.

What can you tell us about Lemaître’s approach to the intersection of science and faith, and what can we learn from it nearly a century later?

His conception of the relationship of science and faith was rather circumspect, carefully delineating their roles as ways of knowing. Science for him was the methodology for understanding the physical cosmos; revealed religion taught truths important for salvation. He was quite content to observe that the findings of science were in no way discordant with scriptural revelation, and vice versa, but neither should overreach. If Lemaître has a lesson for the science-faith discourse today, that would probably be it.

As a mathematical physicist and cosmologist, he would undoubtedly applaud today’s bold theoretical forays into multiverses, large extra dimensions, etc., but he would certainly look askance at the metaphysical extrapolations some would attempt to leverage from them, particularly when such theories so far lack any contact with experiment, and thus fail the test of falsifiability.

Interestingly, the one aspect of the Genesis accounts of creation that Lemaître insisted should be taken literally was the divine mandate to observe the Sabbath rest. A full day of rest each week; there’s a lesson we would all do well to learn.

Science for Georges Lemaître was the methodology for understanding the physical cosmos; revealed religion taught truths important for salvation. He was quite content to observe that the findings of science were in no way discordant with scriptural revelation, and vice versa, but neither should overreach.

As a physicist and Catholic, how do you pray?

As I get older, I find myself praying more and more for people: family, friends, colleagues, my students, happenstance meetings with strangers, human tragedies in the news. Everyone has their problems and travails, everyone; I’ve lost track of how many friends of mine who are dealing with cancer or other grave illnesses. Work done perfectly and as service can be turned into prayer; I try to do that. I read some words of Mother Teresa, her addresses and interviews, every night before retiring; it keeps me grounded.

What’s your favorite Scripture passage and why?

I’m not sure about a favorite scriptural passage, but I definitely have a favorite incident, which is the riot of the silversmiths during Paul’s stay in Ephesus, in Acts 19. It’s hilarious; anyone who’s done time on the Berkeley campus will recognize how true to life it is.

Nuclear energy and its applications is a frequent subject for ethical criticism. If you could say one thing to Pope Francis about your field, what would it be?

Historically, the Roman pontiffs in their magisterial documents usually stick to enunciating general principles rather than proposing specific solutions, so I don’t know what Pope Francis would say about nuclear power. It is demonstrably the carbon-free solution to the base energy needs of a rapidly growing world, and more and more serious environmentalists are turning around on the issue. Thus in light of Francis’ recent watershed encyclical on the environment (“Laudato Si’ – On Care for our Common Home”), I would hope he would look favorably on it.

What’s your next big project?

I would be quite satisfied just to bring some of my old projects to closure. For close on 30 years, I’ve been involved in a search for the dark matter of the universe; were he still here, Monsignor Lemaître would surely have some valuable insights and guidance for us.

Sean Salai, S.J., is a contributing writer at America.

Thanks everyone for reading. Inspired by the example of Monsignor Georges Lemaitre, the Catholic priest and scientist who proposed the Big Bang theory, let's continue to pray for a greater harmony of faith and science in our world today.