Inherit the Kingdom

Royal symbols often come from other occupations whose work explains the sovereign’s role. The British monarch, for example, is a warrior-priest. At her coronation, Queen Elizabeth II was anointed with chrism and vested with liturgical garments. She also received a sword, a scepter (a ritual spear) and the stylized battle helmet known today as St. Edward’s Crown. These symbols were reminders of her duty to protect the nation morally and militarily.

‘Whatever you did for one of the least brothers of mine, you did for me.’ (Mt 25:40)

How can you strengthen your trust in God?

How does God’s love inspire you to show mercy?

In the ancient Near East, kings drew their symbols from the work of shepherds. The mythic kings of early Mesopotamia incorporated the title “shepherd” into their name (Lugalbanda-the-Shepherd, for example). Pharaohs of Egypt carried a shepherd’s crook among their regalia. In Israel, charismatic founders like Jacob and Moses were shepherds. David was out tending Jesse’s flocks when Samuel came to anoint him. The image of kings responsible for sheep that appears in today’s Gospel passage has deep roots.

As shepherds of their people, ancient kings had a duty to keep them safe. This symbolism is nowhere more apparent than in 1 Sm 17:36. David, fresh from the pasture, bragged that he had already killed a lion and a bear, so he should have no difficulty killing a Philistine. The bravery and skills that protected his sheep would now protect his fellow Israelites.

As protectors, kings also sought out lost sheep. Nearby enemies intermittently raided Israel’s borders and carried Israelites off into slavery. When families could not recapture their lost relatives, it became the king’s duty to seek out and gather those who had been scattered. Shepherds also tended to the needs of individual sheep, as we read in today’s first reading: “The injured I will bind up; the sick I will heal.” The king’s responsibility for justice ensured that every Israelite could thrive. The Israelite king thus had a special care for and duty toward those who suffered misfortune.

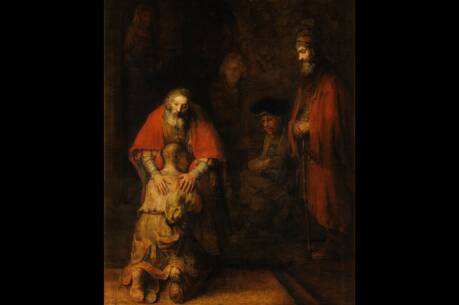

Throughout Matthew’s Gospel, Jesus plays with these images. As Ezekiel implies, the line of David had failed in its duty, so God assumed the shepherding responsibilities personally. Now God sends Jesus to be the new shepherd-king, and his reign will have no end. In today’s Gospel passage, Jesus adds a twist to this teaching. A time is coming when God will act as Ezekiel foretold, but until then the shepherding duty falls to the sheep themselves.

Jesus’ distinction between sheep and goats is part of his message. Although goats will flock to a human leader, they can also survive on their own; in fact feral goats today are a widespread invasive species. Domestic sheep, by contrast, lack the wild instincts to survive. Sheep are thus an apt symbol for humanity’s spiritual condition. Self-sufficiency may be laudable in many ways, but in matters of the spirit, no creature can go feral and survive.

God’s “sheep” know their dependence. Knowledge of their own need for grace opens their hearts to the needs of others. The qualities that make someone a good “sheep” thus also make for a good shepherd.

No better passage could mark the end of another liturgical year. Matthew has provided a compelling account of Jesus’ example, commandments and Spirit. It remains for us, the sheep, to continue the works of mercy that calm anxious hearts with Christ’s promise to remain among us even until the end of time.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “Inherit the Kingdom,” in the November 13, 2017, issue.