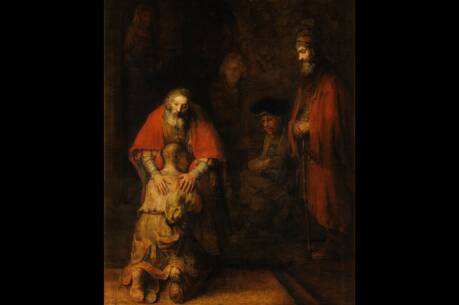

What the parable of the prodigal son can teach us about freedom, duty and love

Today’s Gospel reading contains one of the most beloved passages in the New Testament. The parable traditionally known as the story of the prodigal son appears only in Luke’s Gospel. Although Luke may have been working with traditional material, this narrative reveals his brilliance as a writer. In this parable, Luke presents a complex study of the interplay of freedom, duty and love. The younger son embodies freedom. He leaves when he chooses and returns again as he chooses. The elder son, by contrast, embodies duty. He serves his father without complaint and asks for nothing in return. Both sons, however, lack an essential characteristic. Only the father embodies love, and it is in this that freedom and duty achieve their real purpose.

‘This son of mine was dead, and has come to life again; he was lost, and has been found.’ (Lk 15:23-24)

Do you use your freedom to serve others in love?

Does your obedience to God help you love as Jesus did?

How have acts of love helped you understand the true nature of freedom and obedience?

It is easy to identify the younger son as the villain. His request for an early inheritance reveals a breathtaking insolence. He is, in effect, saying that his father is worth more to him dead than alive. His disrespect comes through again as he squanders his family’s wealth. His choice to return to his father is also morally threadbare. Although he prepares a fine statement calling himself out as a sinner, one cannot deny that his return has as much to do with food as it does with atonement. He recognizes that he himself has suffered through his actions, but he reveals little understanding of the pain he has caused others. His freedom isolates him, causes him suffering and makes him a source of suffering to others.

The elder son, by contrast, is isolated by his sense of duty. He may have never complained, but he silently feels resentment. His obedience is not a token of his love but rather a manifestation of his own ego. He does what is right not in pursuit of some higher ideal, like righteousness or love, but rather as a way of gaining and holding on to his father’s approval. The reappearance of his younger brother reveals the futility of this project when he sees his brother receive on the easiest of terms the validation that he was struggling to achieve. In a way parallel to the younger, the elder’s sense of duty isolates him and causes suffering.

Both sons are lost. Both have developed habits that cut them off from others. Only in the father have freedom and duty achieved their final purpose as symbols of love. The father reveals his freedom from attachments and accedes to the younger son’s demand. This act of love comes at great material and emotional cost, but he does it without hesitation. When the younger son returns, the father’s freedom then allows him to forgive everything and receive the son back.

Likewise, the father’s sense of duty is clear when he leaves the celebration to speak with the elder son. Although he no doubt would prefer to stay with the recently returned younger son, he recognizes that the elder needs his love more in that moment. In his promise, “All I have is yours,” he acknowledges his debt to the elder, and he offers it all to him as a sign of his love.

Jesus offers this parable to illustrate God’s joy at the return of a lost soul. Whenever Christians forget that freedom and duty serve a higher purpose, they run the risk of losing themselves to their own ego. Only those who turn all things toward love will be able to welcome back the lost.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “Freedom and Duty,” in the March 18, 2019, issue.