Night coming tenderly

Black like me-Langston Hughes

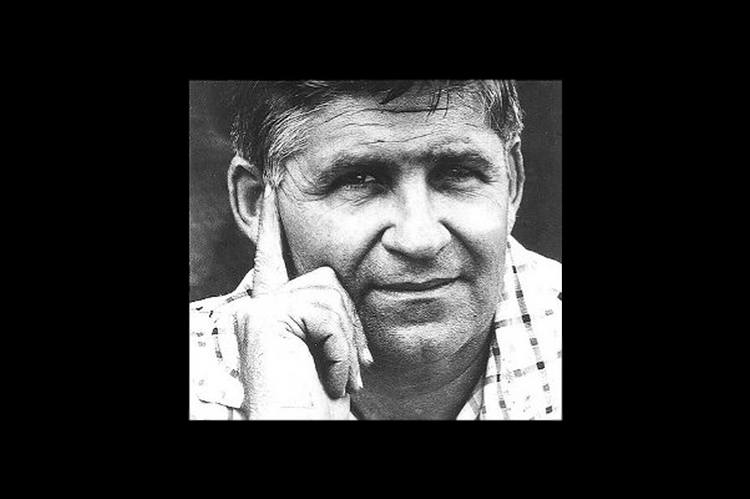

Tomorrow marks the centenary of the writer and activist John Howard Griffin, who was born in Texas on June 16, 1920. His early life was marked by a number of diverse and remarkable experiences. But he is best remembered for his classic work Black Like Me, in which he described his experience in the winter of 1959 when he traveled to New Orleans, darkened his skin, shaved his head and “crossed the line into a country of hate, fear, and hopelessness—the country of the American Negro.”

Perhaps the roots of Griffin’s experience lay in his earlier 10-year experience of blindness—the result of a war injury. This experience prompted a deep spiritual journey that included his conversion to Catholicism. When his sight later miraculously returned, he was struck by how much superficial appearances can serve as obstacles to perception—allowing us to regard certain fellow humans as the “intrinsic other.” This was especially obvious in the case of racism. Yet Griffin was struck by the frequent challenge from black friends: “The only way you can know what it’s like is to wake up in my skin.” He took these words to heart.

Griffin’s book went beyond social observation to examine an underlying disease of the soul. His book was really a meditation on the effects of dehumanization, both for the oppressed and for the oppressors themselves. “Future historians,” he wrote, “will be mystified that generations of us could stand in the midst of this sickness and never see it, never really feel how our System distorted and dwarfed human lives because these lives happened to inhabit bodies encased in a darker skin, and how, in cooperating with this System, it distorted and dwarfed our own lives in a subtle and terrible way.”

‘Black Like Me’ went beyond social observation to examine an underlying disease of the soul.

After his story was published, Griffin was exposed to a more personal form of hostility. His body was hung in effigy on the main street of his town. His life was repeatedly threatened. Nevertheless, he threw himself into a decade of tireless work on behalf of the growing civil rights movement. Necessity forced him, much against his nature, into the role of activist. “One hopes,” he wrote, “that if one acts from a thirst for justice and suffers the consequences, then others who share one’s thirst may be spared the terror of disesteem and persecution.” And so he persevered with those who shared “the harsh and terrible understanding that somehow they must pit the quality of their love against the quantity of hate roaming the world.”

Along the way, Griffin became a close friend of the Trappist monk Thomas Merton. They shared not only a passion for racial justice but also a conviction that the conflicts rending American society in the 1960s had their roots in a deeper spiritual disorder. Griffin also encouraged his friend’s growing interest in photography. After Merton’s death, he published a volume of Merton’s photographs and was invited to serve as his official biographer. Though his declining health left him unable to finish this project, he did complete a short treatment of Merton’s hermitage years, Follow the Ecstasy.

For years, Griffin had suffered from a range of ailments, including severe diabetes and other problems possibly induced by the skin treatments he had undergone years before. He died (of “everything,” according to his wife) on Sept. 8, 1980.

It is fitting to remember John Howard Griffin in the midst of a general uprising inspired by the slogan “Black Lives Matter."

I never met Griffin. Like many people, I had read Black Like Me in school, without knowing much else about the author or truly understanding the spiritual message of his book. I truly met him for the first time when I read his obituary, shortly after returning to college after five years at the Catholic Worker. I was instantly drawn by his story and spent the next several months reading everything by and about him that I could find. I was fascinated to learn, for instance, that upon discovering that he was losing his sight he returned to France to prepare himself for blindness by living in the Benedictine Abbey of Solesmes, studying Gregorian chant; that returning home he took up ranching, married his piano teacher, published two novels and fathered two children, whom he saw for the first time when a blockage to his optic nerve suddenly opened, restoring his sight. I wrote about all this in an essay on Griffin’s life that appeared in the same issue of The Catholic Worker that announced the death of Dorothy Day.

What, I asked, was the purpose of all this experience? Perhaps to see what others could not see and to report on his vision. So he had entered the second half of his life. I learned that an interviewer had once asked him about the “unparalleled risk” he had taken in dying his skin. “What people don’t really know,” Griffin replied, “is that long before this I took another great gamble, what the French call ‘the great Yes.’ The gamble was for God. That means leaping off that cliff and never knowing where you’re going to land, but you have the faith that you’re going to land somewhere.”

It is fitting to remember Griffin’s life in the midst of a general uprising inspired by the slogan “Black Lives Matter.” Perhaps that slogan bears a different weight, depending on one’s location on the color line. What for African-Americans is an assertion of human dignity in the face of systemic racism is, for white people, a call to empathy and to relinquishing the mantle of white privilege. Griffin’s was a life devoted to radical empathy and a quest to discover what it means, finally, to be a human being.

“The world,” he once wrote, “has always been saved by an Abrahamic minority.” In the marches and protests that have spread across the country and around the world, he would perhaps be encouraged by signs that that minority is growing.