In an interview on Italian television last month, Pope Francis was asked what he thinks about hell. The pope responded that hell is “difficult to imagine” and added that, in his personal opinion, he “like[s] to think hell is empty; I hope it is.” Even though Pope Francis was abundantly clear that his statements were “not a dogma of faith,” they sparked a backlash from those who, apparently, really do hope that people are being tortured for all eternity and have no problem admitting to it.

Several critics fell back on the tried and trusted “Hitler fallacy” (the pope hopes to see Hitler in heaven?), while others judged that the pope was preaching the ancient heresy of universalism. Most common of all was the troubling sentiment that if everyone goes to heaven, why follow Jesus at all? Truly, if the only thing preventing Catholics from becoming serial killers is fear of God’s justice, then we have much bigger problems. But the incident revealed that many people like to take their Christian eschatology straight up, without the diluting effects of divine mercy and forgiveness.

If Hades is familiar to us from Robert Graves or Disney’s “Hercules,” then many of the infernal spaces described by Jesus seem obscure.

As a Bible scholar and historian of early Christianity, my interest was piqued. It is certainly worth asking: What is hell for? After all, as is well known to readers of the Bible, it was not always there. The closest we come to hell in the Old Testament is Sheol, a place of darkness for an undifferentiated mass of saints and sinners. It was only after Alexander the Great’s conquest of the Levant that Greek mythology started to wend its way into biblical visions of the afterlife. The story of the rich man and Lazarus in Luke explicitly identifies the condemned man as languishing in Hades. We can practically hear the scrapes of Sisyphus pushing his boulder up the hill.

But if Hades is familiar to us from Robert Graves or Disney’s “Hercules,” then many of the infernal spaces described by Jesus seem obscure. In the Gospels, Jesus refers—usually in parables or other evasively symbolic stories—to a variety of spaces that are unfamiliar to modern readers. There is a place of “outer darkness” where people weep and their teeth chatter (or gnash if you prefer that translation). This is quite different from the fire-filled caves pictured in European artwork and modern pop culture. How can hell run both hot and cold?

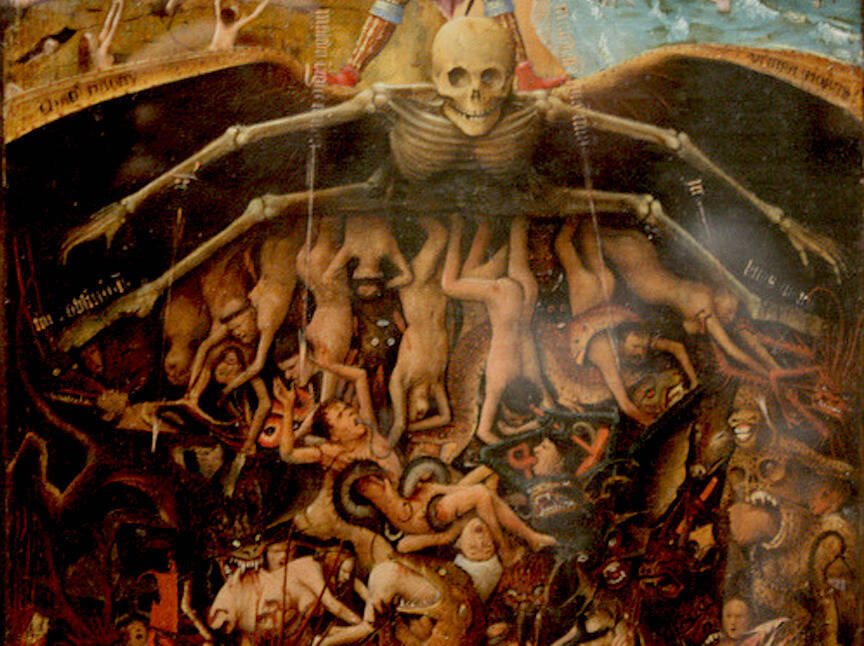

Not until late antiquity did the impression of hell that we only faintly sense in the Gospels—whiffs of sulfur, flashes of flames, the hair-raising wriggle of worms—begin to flourish. Tours of hell, allegedly given to religious heroes in visions, reveal the ever-expanding scale of the underworld. The apocalypses of Mary, Peter, Paul and other non-canonical writings from the early Christian era flesh out the details of the subterranean torture chamber. Disobedient Christians, unlucky pagans and merciless persecutors find themselves shackled and buried in a world of grime and pain. By the time we get to Dante, we have a multistoried hell of epic proportions.

These stories might be nightmarish to us, but in antiquity, they worked precisely because they drew from the conditions of real-world captivity. As the cutting-edge exploration of Roman carceral spaces by archeologists Matthew Larsen and Mark Letteney explains, these were not hypothetical spaces. The inspiration for hell was actual incarceration. Architecturally, we can map hell’s floorplan onto the various spaces used for legal proceedings, incarceration and punishment: Hell is carved not out of the imagination but out of the rocks of real underground prisons, slave quarters and mines.

Even seemingly abstract statements had real-world referents. The strange language of “outer darkness” gestures to the ordinary spaces of domestic and agrarian punishment in which enslaved and incarcerated people were chained to walls at night. A victim of Vesuvius, for example, was found by archaeologists still shackled to a wall in a storage room off an underground kitchen in Pompeii. Although Pompeii conjures images of fire, before the eruption, most of those restrained found themselves exposed to low nighttime temperatures where their teeth really did chatter from the cold. So, too, those incarcerated in the windowless prison chambers farthest (that is, outermost) from light sources in Roman prisons were also confined in darkness.

As it has emerged in Christianity, hell is a prison that replicates the dire working and living conditions of those enslaved and incarcerated by the Roman penal system.

Ancient imprisonment can also explain the scatological themes present in Christian speculation about hell. As Larsen and Letteney show in their work, cesspits were a rare luxury for the incarcerated. Instead, fecal matter was everywhere—and teeming with the wriggle of intestinal parasites. The stench of human excrement filled such spaces. Similarly, in hell, people from every rank were consumed by parasitic worms or buried up to their waists and necks in excrement.

Other ancient prisoners were dispatched to mines, where they were usually physically exhausted and thirsty. Further, they ran the risk of suffocating from noxious gases or being trapped under falling rocks and debris. These working conditions explain why, from antiquity to Dante, the lower spaces of hell were reserved for the most sinful, why sinners find themselves trapped under rocks and why sulfur perfumes the air of hell. Stories about the conditions quarried fear alongside copper and marble. St. John Chrysostom, the fourth-century bishop of Constantinople and fabled preacher, could trade on this anxiety when he told his parishioners that hell is like the mines, only worse.

As it has emerged in Christianity, hell is a prison that replicates the dire working and living conditions of those enslaved and incarcerated by the Roman penal system. Since none of us would support these conditions in the real world, it is curious that some insist on them in eternity.

But there are some critical differences between real and infernal punishment: Many of those consigned to hell in the parables are those who mistreat their social inferiors. In real life, the wealthy could avoid subterranean prisons and mines, but in the everlasting kingdom of God, everyone faced the same kind of brutal judgment. This does not make the vision of hell more palatable, but it explains why hell’s existence was appealing to those who were socially marginalized.

This does not mean, however, that the parables of Jesus or tours of hell described actual eternal punishment. Many of those sent to the mines, Letteney and Larsen show, emerged from their confinement to live out the rest of their lives. So, too, in her book Hell Hath No Fury (Yale, 2021), Meghan Henning reveals that late antique descriptions of infernal torture are teaching tools. Vivid images of punishment existed to scare people and to dissuade them from sin. In the images of hell influenced by Plato, Henning’s work shows, the fires of hell are purgative: They burn the sin out of you so you can start again. These were spaces of punishment, not spaces of damnation.

The prisoners of the Inquisition who were housed in the 17th-century Palazzo Chiaramonte-Steri in Palermo, Sicily, filled their time inscribing the prison walls with images and words in Italian, Arabic, English and Sicilian. Several of them painted hell mouths summoned from Dante’s “Inferno.” Inside one monster, we read Dante’s words: “Abandon all hope, ye who enter.”The gaping jaws of the mouth open like a crescent moon as a procession of biblical patriarchs spill out into the world led by Christ.

To these prisoners, the harrowing of hell was a source of hope. Surely Francis is right to hope that hell is empty. After all, there is a precedent for freeing its occupants.