Read Part I of the interview with Archbishop Jorge Ignacio García Cuerva here.

In Part II of this exclusive interview with America’s Vatican correspondent on Feb. 15, the Most. Rev. Jorge Ignacio García Cuerva speaks about the challenges he envisages as archbishop of Buenos Aires. He also discusses the role of the Catholic Church in Argentina under a new president, Javier Milei, who is keen to reverse the country’s grave economic crisis but appears less committed to dialogue in his efforts to do so.

‘Bergoglio’s diocese’

Archbishop García Cuerva began by recalling that one of the conclusions of the first synod in Buenos Aires (2017-21) was that “God lives in the city.” So, he said, “if God lives in the city, then we must go out to meet him.”

“The great challenge today is not only to be the archdiocese of Bergoglio; it is to be the church of Francis,” he said. “Everyone speaks about Bergoglio, the curia, the people in the parishes remember him. He left his mark on the archdiocese.” But, the archbishop insisted, “I want us to be the church of Francis, not just the diocese of Bergoglio. What’s the difference? I want us to really know and concretize his magisterium.”

“We have to make ‘Evangelii Gaudium’ a reality. We must make a reality Francis’ words, his documents, his vision of the church as a field hospital, as a church that goes out to the frontlines. We have to be a church whose shrines are oases of mercy, a church whose pastors are close to the people, where the youth, the laity, the women, have a leading role.”

Space for women

Speaking of women having a leading role in the church of today and tomorrow, the archbishop pointed to Mama Antula, Argentina’s first woman saint. He was one of the main concelebrants at her canonization in St. Peter’s Basilica on Sunday, Feb. 11.

The archbishop remarked, “We learned throughout history that even though the church did not recognize the sainthood of a person [early on], the simple people often did.” He admitted, however, “she was a totally unknown figure” for him in the 1980s. But he insisted that she did not just become recognized as a saint “because there is an Argentine pope.” On the contrary, he said, “I believe that the marks of holiness of Mother Antula transcend the figure of the pope. Indeed, she has the marks of holiness that Francis speaks about in Chapter 4 of the exhortation ‘Gaudete et Exultate’—joy, boldness, meekness, perseverance, patience, community awareness and prayerfulness…. I think these marks have found their way into the hearts of our people.”

“We have to make ‘Evangelii Gaudium’ a reality. We must make a reality Francis’ words, his documents, his vision of the church as a field hospital, as a church that goes out to the frontlines.

Her message is “highly relevant for the church today, especially regarding the protagonism of lay women,” he said. “I believe that in God’s providence perhaps this had to be the moment [for Mama Antula’s canonization] because this is the moment when we are walking between one synod and another, and in which the figure of women as protagonists in the church and in society is being discussed.”

The challenge of poverty

Throughout his priesthood, Archbishop García Cuerva has worked in situations of great poverty, both in the shanty towns and in the two dioceses where he has been bishop. As archbishop of Buenos Aires, he is destined to play a leading role both in the bishops’ conference and in Argentina, a country rich in natural resources that was one of the richest countries in the world at the beginning of the 20th century but is in deep economic crisis today.

I asked what he envisions as the church’s task in a situation where 50 percent of Argentina’s 46 million people live in poverty, with inflation exceeding 250 percent, under a new president who aims to ‘make Argentina great again.’

Looking back at the past half-century, Archbishop García Cuerva noted that many parties—Peronists, radicals, the military—are responsible for the country’s impoverishment and said that “today there must be some responsibility on the part of everyone to reverse that reality.”

“We have to take our homeland on our shoulders, as Francis said on more than one occasion,” Archbishop García Cuerva said. “I believe we must take care of Argentina, which is hurting, and commit ourselves to taking it forward.”

“The church itself does not have an economic recipe, nor do we make plans of government,” he acknowledged. Nevertheless, he said, “we have a great possibility to make concrete the magisterium of Francis by making the culture of encounter happen, by generating the social model that Francis proposes in ‘Evangelii Gaudium’ of the polyhedron, whereby nobody is expendable, nobody is to be thrown away.”

“I think the church has its own contribution to make to the reconstruction of Argentina,” he said.

Speaking from his 20 years of experience in the shanty towns, he said: “For me the greatest inequity and inequality is in [the field of] education. I am convinced that education is the only thing that takes us out of the hard core of poverty…. And if we do not have equal educational opportunities, we will replicate a social model of inequity.”

Argentina’s new president

The new president of Argentina, Javier Milei, was present at the canonization in St. Peter’s, but the archbishop did not meet him then Archbishop García Cuerva met the president for the first time Dec. 10, when, after being sworn in as president, Mr. Milei drove to the Catholic cathedral in Buenos Aires for the religious invocation presided over by the archbishop and attended by ecumenical and interfaith Argentine leaders.

“On that occasion,” the archbishop recalled, “I noticed that he [Mr. Milei] is a very religious man, beyond his ties to Judaism. As soon as he entered, he genuflected and made the sign of the cross. He was very attentive during the religious invocation. He is clearly a man of deep spirituality.”

Asked if he was surprised that President Milei embraced the pope at the end of Mama Antula’s canonization Mass, the archbishop said, “I am glad because I believe that in Argentina there is no more room for conflict…. We are in too much trouble to continue dividing. I believe there is no room for hatred. And then with that embrace, [Mr. Milei] seems to me to have put aside his expressions [during the campaign] that were very unfortunate and very painful. In his embrace with the Holy Father, he has shown himself to be a good, respectful man, who, as he himself said, apologized for the expressions he made during the campaign.”

He went on to emphasize that Francis, as pope, “is father of all” and “has an institutional, ecclesial and evangelical responsibility that transcends [issues of the campaign].” In the basilica with President Milei, the archbishop said, “it seems to me that he has once again given us a great lesson, showing that it is time for more hugs and less throwing stones at each other. To take our country on our shoulders means also to sit down with the one who is different from me and look for points of coincidence.”

Archbishop García Cuerva expressed his openness to sitting down and having an in-depth conversation with Mr. Milei but said that as yet there is no plan for such an encounter.

The archbishop believes the task of the church in Argentina is to work to build, to try to bridge the divide. “It’s my role, it’s the role of the church at this time. I think what we have to do is to encourage all [sides] to meet and to generate spaces for meeting, to be willing to dialogue with everyone. To be willing to contribute with proposals if we have them, and to be mediators. Always being at the side of the people. It seems to me that the church will not be mistaken in its mission if it is on the side of the poor.”

He recalled that there has been division in the church, too, and not only in the political world. “Among the baptized we have a lot of differences, don’t we? I understand that in the last election, many [Catholics] probably voted for Milei, others did not. What I do believe is that beyond our differences, we are also challenged to meet within the church

The return of violence

When I asked if he was afraid there could again be violence in Argentina given the present economic tensions, the archbishop said: “I believe that to some degree the violence has not gone away. We are extremely violent with words, attacking each other…. It is violence to ignore or turn one’s face away from those who are most in need. And I think that also happens among us.”

Moreover, he said, “We see that violence exists when we have to make a nonaggression pact with friends and family and agree not to talk about certain subjects, such as politics, football, religion. So we are marked by violence, perhaps not institutional violence, if one compares [today] with what could have been the violence of other years, of other eras, but I think that we attack each other too much. Instead, we need to promote encounter and dialogue.”

A papal visit

Francis has not returned to Argentina since he left Buenos Aires for Rome on Feb. 26, 2013, for the conclave in which he would be elected pope. Over the past year, Francis has said several times that he would like to visit his homeland. Since Archbishop García Cuerva would have a central role in planning any such visit, I asked if he expected the pope, now 87, to return home this year. His answer revealed uncertainty.

“The Argentine people want to meet their pastor, and I am sure that the pastor wants to meet the people. As for the time of the visit, obviously there are a lot of variables that I do not know, and do not manage,” he said.

Among them, he said, is the fact that Francis already has on his agenda a 10-day journey to Papua New Guinea, Indonesia, Singapore and Timor Leste at the end of August, a taxing trip by any standards for a man of his age.

“I, like all Argentinians, want the pope to come to our country. We want the shepherd to meet his people. He also wants to come, but you cannot manage only by your desire. I understand that there are other variables,” he added. “Francis has a responsibility because he is the head of the Catholic Church and a world [figure of] reference not only for us [in Argentina], and this has been difficult for us to understand.”

Coat of arms

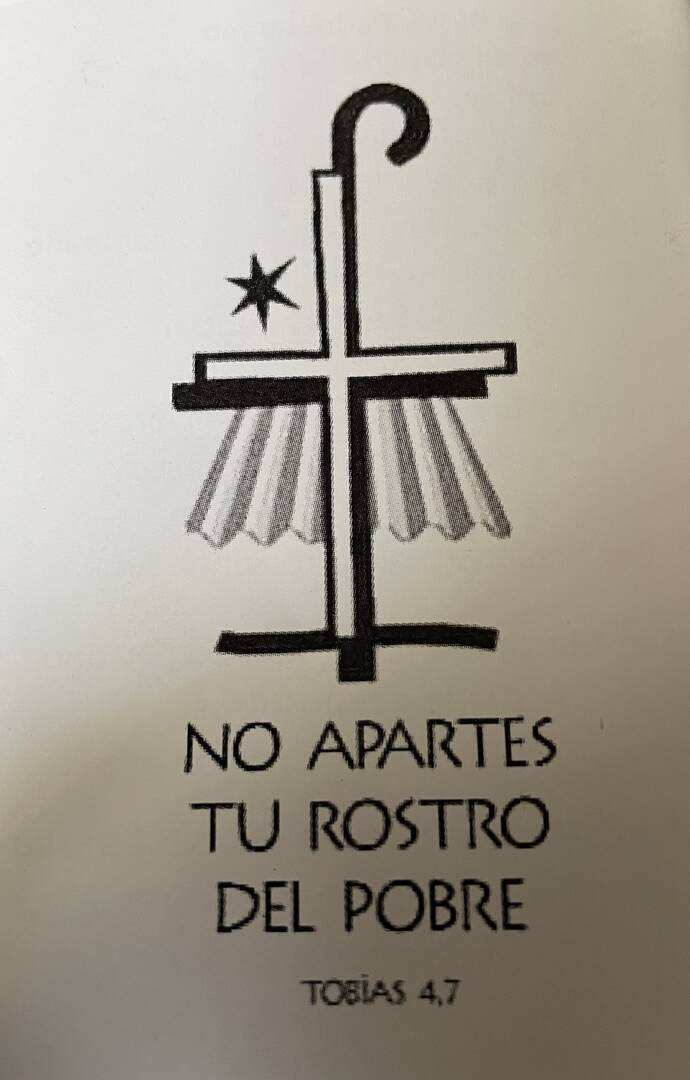

The episcopal coat of arms and the motto a bishop chooses somewhat define the man. Archbishop García Cuerva’s motto is taken from the Book of Tobit: “Do not turn your face away from the poor.”

His coat of arms has five symbols. The first is the cross: “For me, to look at the cross of Jesus is to be reminded a thousand times how God loves us so much that he was able to give his life for us. And so, as bishop, I want to announce God’s love for everyone.”

The second symbol is the crozier. He said this “is the shepherd’s staff, which I put there very close to the cross, because as a shepherd I want to be very close to those crucified today, to those who carry heavy crosses: the poorest, the sick, the lonely, prisoners, young people with drug problems.”

The third sign is the “chapas” or sheet metal that are the roofs of many shanty-town houses, including the ones he lived in. They are not soundproof and represent memories of the cries, sorrows and silences of shanty town life that he carries in his heart.

The fourth symbol is the earth, representing his desire to stay grounded in Buenos Aires. “To be a bishop,” he said, “is to be with one’s feet on the ground, and where my feet are there is my heart.”

The fifth and last symbol is the star “that in a way represents the protection of the Virgin Mary.” It refers to Our Lady of Pompeya, to whom he is particularly devoted, and wears a medal with her image.

The motto and coat of arms of Archbishop García Cuerva reveal the soul of the man whom Pope Francis chose to be pastor of his former archdiocese and to help bridge the divide in the country at a time of great crisis.