Before the month-long meeting of the Synod on Synodality last October in Rome, delegates were invited to a pre-synod retreat led by Timothy Radcliffe, O.P. Part of the purpose of the retreat was to prepare us to participate in “a conversation in the Spirit,” to use Pope Francis’ definition of the synodal process.

I consider this reframing of synodality to be nothing short of revolutionary. Father Radcliffe’s reflections convinced me that the pope’s reframing of the scope and meaning of synods will also have staying power because this reframing opens up a new “model for the church,” to use a term coined by the late Cardinal Avery Dulles, S.J., 50 years ago.

What was so revolutionary?

Prior to the present Synod on Synodality, there have been 15 General Synods in the history of the church, dealing with a range of topics, such as evangelization, priestly formation, the Eucharist and the sacrament of penance. These have been organized in accord with what we read in canon 342 of the 1983 Code of Canon Law:

The synod of bishops is a group of bishops who have been chosen from different regions of the world and meet at fixed times to foster closer unity between the Roman Pontiff and bishops, to assist the Roman Pontiff with their counsel in the preservation and growth of faith and morals and in the observance and strengthening of ecclesiastical discipline, and to consider questions pertaining to the activity of the Church in the world.

Bishops and, at some of the more recent synods, priests and laypeople who were present gathered in small discussion groups, the results of which were reported to the full body. Participants also were allowed three to four minutes to speak in the general sessions, but rarely did the interventions flow thematically from one to another. There was little open discussion or debate. In fact, I was told by a seasoned bishop who attended a number of the earlier synods that bishops were counseled to refrain from bringing up sensitive issues.

A new way of proceeding

All of that changed with Pope Francis, especially with the Synod on Synodality. A major shift involved expanding the voting membership beyond bishops. Lay women and men, religious, priests and deacons are now directly nominated by the pope to participate in synods. All have an equal say and an equal vote. But the most significant change was the redefinition of the synod as a “conversation in the Spirit.” As described in the synod’s preparatory texts, the delegates were asked to participate in the synod not by concentrating on what they or others would say but rather by asking the participants to give priority to the “capacity to listen as well as the quality of the words spoken.”

Conversations in the Spirit “means paying attention to the spiritual movements in oneself and in the other person during the conversation, which requires being attentive to more than simply the words expressed. This quality of attention is an act of respecting, welcoming, and being hospitable to others as they are,” the document continued. “It is an approach that takes seriously what happens in the hearts of those who are conversing. There are two necessary attitudes that are fundamental to this process: active listening and speaking from the heart.”

As a practical consequence of giving priority to listening to the Spirit as the protagonist in our conversations, instead of gathering in an aula, which most resembles a lecture hall, where all of us would be facing the same direction, each of us would take our place at a round table with six to eight other delegates. We would be asked to participate in a series of conversations with interludes of silence to allow us to really listen to what was said by the others. In sum, instead of giving speeches, we were to talk to and listen to one another.

I have to admit that despite the clarity of the pre-synod explanations, I did not fully grasp what was being asked of me as a participant until I attended the retreat given by Father Radcliffe. His three-day retreat set the stage because it provided an experience of a true conversation in the Spirit.

He accomplished this by first putting us in touch with what was in our hearts as we gathered in synod. We came to Rome, he acknowledged, with the same fears about the synod that are present in the wider church. He also gave us permission to bring our own experiences of church to our conversations, realizing that different ecclesiologies would be represented in the room. And finally, he skillfully unpacked the Second Vatican Council’s vision for renewing the church so that we would be solidly anchored theologically. As a result, his six meditations helped to shape our thinking about how to relate and respond to each other as synod participants, thus giving us the capacity to have the kind of conversations that could lead to conversion.

I have selected three of Father Radcliffe’s insights that I found particularly helpful. First, as a pathway for us to confront our fears, doubts and divisions, he invited us to walk together courageously with a Eucharistic hope. Second, he urged us to offer each other the friendship of Jesus, and third, he asked us to recognize and accept that each person speaks with authority and should be honored.

Eucharistic hope in a time of division

Father Radcliffe began our retreat by noting that he was greatly encouraged by the response to Pope Francis’ call for a synodal church. “We are gathered here because we are not united in heart and mind,” he noted, given the many existing and potential divisions in the church. However, “the vast majority of people who have taken part in the synodal process have been surprised by joy.” He continued: “For many, it is the first time that the church has invited them to speak of their faith and hope.”

What a wonderful way to put it. Father Radcliffe frankly acknowledged the reality of the situation: that we were gathered in a moment of promise but also of trepidation, because we knew that we were not yet united. But he reassured us, and indeed the whole church, that those who embrace the synodal way have found themselves surprised—surprised by joy.

Our retreat director cautioned us to be honest and admit that we arrived in Rome with competing hopes, divided and fearful about what lies ahead for a synodal church. Some were hoping for very significant reforms. Many doubted anything significant would change. Others feared that too much would change and that those changes could lead to schism.

Father Timothy offered the Gospel scene of the transfiguration as a metaphor to help us confront our fears, doubts and divisions on the retreat. He pointed out that we are not unlike the disciples at the “first synod,” as he called it, the one in which they made their way to Jerusalem, where Jesus would suffer and die. The Lord’s prediction of his demise left them fearful and divided over conflicting hopes. Peter had his hopes about Jesus, the one he had just proclaimed as the “Christ, the Son of the living God” (Mt 16:16). The mother of James and John hoped her sons would replace Peter and sit at the right and left hand of Jesus.

It was at this moment, walking together on the way to Jerusalem, that Jesus took Peter, James and John on retreat to Mount Tabor to offer a much wider vision of their journey. We should imagine that he is doing the same for us on this retreat, Father Timothy said.

On that occasion, Jesus revealed the expansive view of his mission, including the end of the story, for he was transfigured in glory as the beloved Son of God before their eyes and they heard the Father say, “Listen to him” (Mt 17:6). This encounter did not resolve all their fears and divisions. But it gave them the courage to be on their way to Jerusalem. On Mount Tabor they received a glimpse of the new hope that Jesus would give the world on the night before he died.

Later, in the upper room, when there seemed to be no future, no hope and all that lay ahead was failure, suffering and death, Jesus “made the most hopeful gesture in the history of the world,” Father Timothy told us. At table together, where they had often shared life, Jesus offered them bread and wine and said, “This is my body, given for you; this is my blood poured out for you.” Precisely in the moment, when all was lost, he demonstrated a hope beyond our imagining by giving himself totally.

So, too, now, our Dominican preacher suggested, the Lord invited us on this “Tabor on the Tiber,” as it were, before we set out on walking together, aware that it will involve a kind of dying for us to have new life. The same Jesus offers us in a fresh way the hope found in the Eucharist as he “lead[s] us onwards towards the death and resurrection of the church.” It is a hope that “makes the conflict between our hopes seem minor, almost absurd.” It is a hope that inspires us never to be discouraged that what is being asked of us seems beyond our means or that it will be too costly.

Father Timothy encouraged us to be ready, like the young man in the Gospel who offered his basket of loaves and fishes, to “give generously whatever we have in this Synod, [for] that will be more than enough. The Lord of the harvest will provide.”

That same Eucharistic generosity should compel us never to discount the value of what others offer because we disagree or think it too little. When tempted to reject or marginalize others because they fall out of the norm, we should keep in mind that Catholic theology has always been defined in terms of both/and: Scripture and tradition, faith and works. And so, as Catholics, when we listen to one another, instead of saying, “No,” we should be open to saying, “Yes, and…”

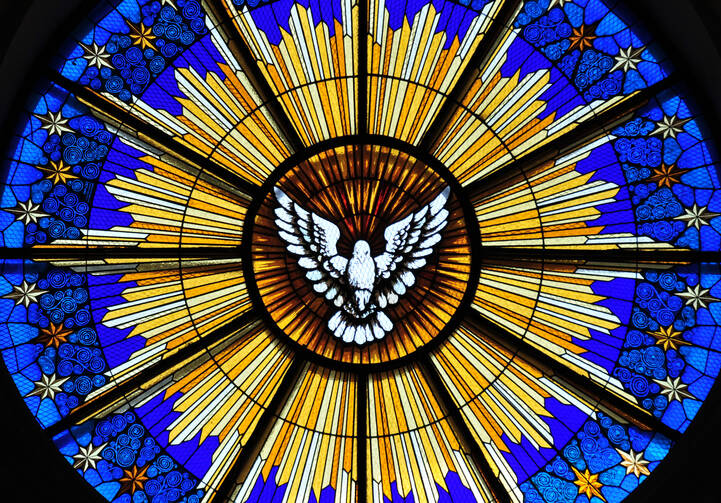

Father Timothy offered another image to encourage us to respect marginalized voices during our synodal conversations. “Renewing the church, then, is like making bread,” he told us. “One gathers edges of the dough into the center and spreads the center into the margins, filling it all with oxygen. One makes the loaf by overthrowing the distinction between the edges and the center, making God’s loaf, whose center is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere, finding us,” Father Timothy offered. So too, it is in listening to each other, folding margins to center and center to margins, that we become open to the breathing of the Holy Spirit in bringing about a renewed church.

This is the hope we receive in the Eucharist and which should inspire us to be generous in our conversations in the Spirit. It is a hope that calls us beyond all division and eases our fears and, more important, our grip on our competing hopes, trusting that what lies ahead is beyond our imagination, but the Lord is with us.

Recounting an incident from his days as a young Dominican provincial superior, Father Radcliffe told us that he and an elder Dominican, Father Peter, paid a visit to a small group of nuns and told them the future of their monastery was uncertain. “One of them objected, ‘But, Father, our dear Lord would not let our monastery die, would he?’ Father Peter replied, ‘Sister, he let his son die.’ So, we can let things die, not in despair, but in hope, and to give space for the new.”

The friendship of Jesus

When I returned from Rome after the synod, I was asked many times, “What happened at the synod?” I simply replied, “I made a lot of new friends and no new enemies.” In fact, Father Radcliffe urged us to intentionally start making friends over the weeks of the synod but to do so in the way that God makes friends. Unlike the human friendships of ancient times, often possible only between the good and among equals, God offers friendship in sometimes shocking ways, to Jacob the trickster, David the murderer and adulterer and Solomon the idolater.

Similarly, Jesus made friends by eating with sinners and visiting their homes. Jesus reveals God as having no boundaries when it comes to making friends: By sending his son to take on our fleshly and earthly existence, God reached across the division between the creature and the creator, between time and eternity, to make friends with us.

The synod is a moment, Father Timothy argued, for us to recalibrate how we make friends. He urged us to ask ourselves whether we have set limits on whom we befriend and if doing so has harmed our ability to listen to each other. This is the kind of listening referred to in the preparatory document I quoted earlier, paying attention to the spiritual movements in oneself and in the other person during conversation, by respecting and welcoming others as they are. It is a recognition that the Spirit of God works in everyone—yes, even those who disagree with us.

Father Timothy observed that God makes friends just as God creates, by letting things be. “Let there be,” God says in the act of creation. So, too, we should not be afraid of people who are different from ourselves or who differ with us on certain issues. These kinds of friendships free us to share our doubts and seek the truth together, regardless of our starting points. Indeed, the very act of truth-seeking is best done together, because in a fundamental way we all need one another in order to make that journey.

He reminded us that seeking truth can never be reduced to just seeking information that we then decide to agree with or challenge. It is not a matter of figuring things out, coming up with new ideas or strategies, which is often the default approach that Americans take when facing challenges. Rather, the aim is to discover the truth that the Spirit reveals, and this requires attentiveness. Conversation in the Spirit yields real fruit in a process of discovering what already is given by God. This is why Pope Francis has repeatedly insisted that the synod is not a parliament, where arguments are made and compromises are sought in a dialectic exchange.

Seeking truth in the synodal process comes in the kind of conversation that asks what is in the heart of another, what troubles and worries the other. This is how God converses with us, as we see in the first conversation God has in the Book of Genesis. After the fall, God does not start a conversation with Adam by accusing him. God does not ask him to pay for the fruit he stole! Rather, God simply asks, “Where are you?” (Gn 3:9). It is a question that shows concern. So, too, along the road to Emmaus Jesus inquires, “What are you talking about?” (Lk 24:17). He asks the disciples to share their anger and their fear. And he is willing to go where they are going, not controlling the conversation or the direction of the journey but accepting their hospitality.

This is how our conversations in the Spirit should occur: listening to what is in the heart of the other person, not trying to control the conversation and not being afraid where the conversation will go. Timetables should be set aside. There is no schedule for completion. Time is in God’s hands, a reality that is particularly challenging for Americans.

What is required is the kind of conversation that leads to conversion. It is a conversation between friends who listen with the imagination and who try to understand why the other holds a position that is different from their own. It is a friendship that takes risks, just as Jesus did when, on the night before he died and his disciples were about to betray, deny and desert him, he told them, “I call you friends” (Jn 15:15).

Mutually enhancing authority

“There can be no fruitful conversation between us,” Father Timothy warned, “unless we recognize that each of us speaks with authority.” He pointed out that the International Theological Commission quoted St. John when addressing the topic of the sensusfidei: “You have been anointed by the Holy One, and all of you have knowledge…the anointing that you received from (Christ) abides in you, and so you do not need anyone to teach you…his anointing teaches you about all things” (1 Jn 2:20, 27).

Many laypeople involved in the synod were astonished that, for the first time, church leaders actually listened to them. But none of the delegates should doubt their authority to speak. All of us, no matter our position in the church, must proceed from a common understanding that “authority is multiple and mutually enhancing.” One simple gesture indicated to me that Father Radcliffe’s urging in this regard took root in the hearts of the synod delegates. As we sat around the table, the facilitator began by asking us one simple question: “How do you want to be called?” Everyone, no matter their position in the church, gave their first name and omitted any reference to a title. We began on equal footing and recognized that each speaks with authority.

We have good examples in the early church of speaking truth to power that should guide us. Paul recounts in his Letter to the Galatians that he opposed Peter “to his face” (Gal 2:11), and still they gave each other the right hand of fellowship—and the church honors them as founding martyrs. Following their example, we should “seek ways to speak the truth so that the other person can hear it without feeling demolished.”

Fear is often behind the hesitation to speak the truth when it is uncomfortable. Those speaking hesitate because they fear rejection. Those hearing the truth fear it will require giving up control or change. “We have a profound instinct to hang on to control, which is why the Synod is feared by many,” said Father Radcliffe. Yet, from the earliest days of the church, the Holy Spirit has challenged this tendency to control or maintain the status quo. Father Timothy recalled that at Pentecost, “the Holy Spirit came powerfully upon the disciples who were sent to the ends of the earth. But instead, the apostles settled down in Jerusalem and did not want to leave. It took persecution to ease them out of the nest and send them away from Jerusalem.” This is God’s way of exercising “tough love,” he joked.

Leaders especially need to be observant of the fear of letting go of control and being open to change, “for being led by the Spirit in all truth means letting go of the present, trusting that the Spirit will beget new institutions, new forms of Christian living, new ministries.” This is in keeping with the counsel of Pope Francis in “The Joy of the Gospel,” where he wrote: “There is no greater freedom than that of allowing oneself to be guided by the Holy Spirit, renouncing every attempt to plan and control everything to the last detail, and instead letting him enlighten, guide and direct us, leading us wherever he wills” (No. 280).

The fear of losing control runs deep in the psyche of church leadership, and it would be easy to recount many examples. One of my favorite ones is found in a letter written by Cardinal Wolsey to Pope Clement VII in 1525. As you may recall, Cardinal Wolsey was the king of England’s almoner and became the controlling figure in virtually all matters of church and state under Henry VIII. His appointment as a cardinal and legate to England by Pope Leo X gave him precedence over all other English clergy, and as lord chancellor he enjoyed great freedom and was often depicted as the alter rex (“other king“). With the development of the printing press, he felt a duty to warn the pope of the dangers of this new invention, noting that it would have the sorry result of making Scripture and the beliefs of the church directly available to the laity. Were this to happen, he warned, the laity would be encouraged to begin “praying on their own in their vulgar languages,” and if they did that, they might think it possible to make their own way to God—and then there would be little use for the clergy.

But, as Father Timothy reminded us, authority is not a zero-sum game. Rather, it “is multiple and mutually enhancing. There need be no competition, as if the laity can only have more authority if the bishops have less, or so-called conservatives compete for authority with progressives,” he counseled. Instead of acting like those disciples who wanted to call down fire on their opponents, we should model ourselves after the Trinity, where “the Father, Son and Holy Spirit do not compete for power, just as there is no competition between our four Gospels.”

A transformative power

The transfiguration experience on Mount Tabor gave the disciples of Jesus a glimpse of his mission. It did not resolve all their divisions, fears and competing hopes, but it did give them the courage to take their first steps with Jesus as he made his way to Jerusalem. Father Radcliffe’s retreat meditations served a similar purpose. By revealing the transformative power of Eucharistic hope that can quell our fears, of friendships that are attentive to the movement of the Spirit in one another, and of recognizing one another’s mutually enhancing authority to participate in the life of the church, he emboldened us to take our place in the synod hall and participate in “a dynamic,” to quote the Instrumentum Laboris for the synod,“in which the word [that is] spoke[n] and heard generates familiarity, enabling the participants to draw closer to one another.”

But his talks did even more. They helped us to understand that the Holy Father is calling us to envision a renewal of the whole church as a conversation in the Spirit. It is a new “model of the church,” which I believe has the promise of bringing about a renewal for how we make decisions in the church and how we relate to one another at the universal, continental, national and local levels. Just imagine what it could mean if national and provincial episcopal conferences, presbyteral and archdiocesan lay councils and parish councils understood themselves as gathering for conversations in the Spirit. They would take up their mission, inspired by a Eucharistic hope, committed to creating and sustaining friendships by listening to the movement of the Spirit in one another and remaining steadfast in respecting one another’s mutually enhancing authority.

My hope is that just as Father Radcliffe prepared us to enter the synod hall, so too will Catholics be inspired to take their place at the table of the synod process and work toward the kind of renewal the pope envisions.

It is not surprising that the first name for the church was “The Way,” for it was at the first synod, when the disciples went to Jerusalem, that they came to understand that the Lord, ever by their side through the Spirit, was the one leading them on the way and that their mission was to discern his movement.

That is the legacy the early church left us, which Pope Francis has made his own—and is inviting us to embrace—so that we, too, can be “surprised by joy.”