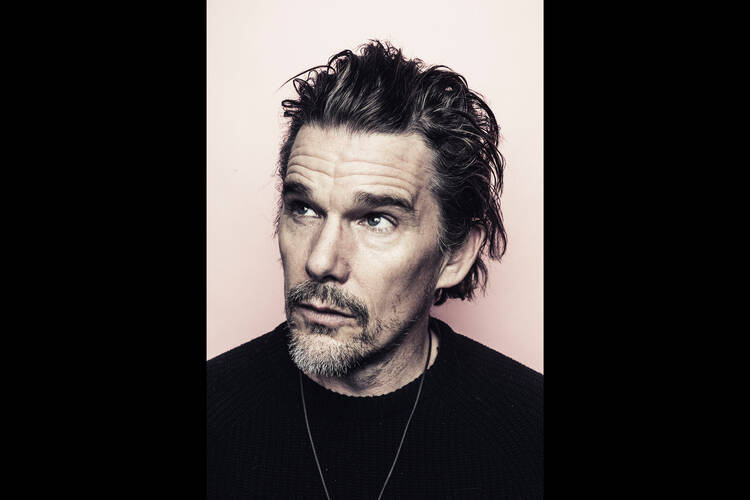

It’s a very special week on “Jesuitical”—Ethan Hawke joins the podcast to discuss his new film, “Wildcat,” about the Catholic writer Flannery O’Connor, who is portrayed in the film by Ethan’s daughter, Maya Hawke. Zac Davis, Ashley McKinless and Ethan share a wide-ranging and profound conversation about this great American writer and the work of bringing her to life in “Wildcat.”

They discuss:

- Ethan’s introduction to Flannery and the inspiration behind “Wildcat”

- Exploring religious questions through art

- Portraying Flannery’s complicated views on race

Below is an excerpt from their conversation. The transcript has been edited for length and style.

Click here to listen to the full episode on Apple podcasts.

Click here to listen to the full episode on Spotify.

Zac Davis: Could start talking about the origin of this film? There’s this real intergenerational aspect to this project that I found so beautiful.

Ethan Hawke: There really is. This movie has made itself manifest in a very strange and difficult way for me. You sometimes feel like the project is making you and that you’re not making the project.

Years ago, my mother and I lived in Atlanta, Ga., and she was selling college textbooks. She was a young woman. She was probably only 28 or something. She fell hard in love with Ms. O’Connor’s work. I remember she drove out to Milledgeville. In our house, it felt like Flannery O’Connor was extremely important because when your parents really love something, you think everybody in the world is celebrating that. I thought she was the most famous author in the history of all time because that’s what my mother talked about.

And then as I was growing up, she was always giving me the short stories. “Have you read that one again?” She was, I think, being careful not to let me turn into a hopeless devotee to the normal knucklehead masculine writers: Hemingway, Faulkner, Kerouac, all that. She was like, “And what about Flannery O’Connor? And what about Flannery O’Connor?”

Then my daughter turned about 15 or 16, and she said to me one day, “Have you read Flannery O’Connor?” Her high school English teacher had been teaching her. I guess they were working on “A Good Man is Hard to Find” and Wise Blood. So we started talking about it. Around that time, Maya discovered[Flannery O’Connor’s] prayer journal, which had a huge impact on her psychic life. It was the first time she’d really asked herself a bunch of life’s most serious and unanswerable questions.

But if you’ve come across that prayer journal, they’re really just letters to God that she wrote between the ages of 18 and 21. They’re very earnest and very sincere, a little self-loathing, a little overconfident at times. She was really trying to wrestle with what the right manifestation of ambition is. She wanted to be a great writer. And she understood that that ambition was a little ugly in relationship to the humility that she strived for as a Christian. What did she want to be great for? Was it in the service of something larger than herself? Or was it just to impress others and be seen as fabulous?

Maya was really struck that somebody who turned out so brilliant could be so insecure, and that those questions of ambition were things that she was asking herself as well. It gave her confidence and solidarity and a sense of friendship with this woman who lived a generation before her. Maya started working on turning the prayer journal into a monologue that she did for drama school. I worked with her on that.

We started getting really interested in the idea of making a short film about the prayer journal. That’s how it started. Then we forgot about it for a couple of years. Then Maya got on “Stranger Things,” and “Stranger Things” started to blow up. She wanted to have a little agency in her own career. She worked with another producer and found out the rights to the stories and her life rights to maybe make a film about her. Then she called me up and said, “You remember that old idea we talked about? What if we made a film about Flannery O’Connor? What would it be like?”

And I pretty quickly had an idea. What is remarkable about her to me is the intersection of faith and imagination. Her devotion and seriousness of her religious life is best communicated through her art. You could kind of make a movie about faith, imagination, and how it intersects with reality using her as a launching pad for such a conversation with the audience.

AM: This isn’t a traditional biopic. It zooms in on that small period of her life when she’s out of college, out of Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and is coming to grips with her diagnosis of lupus. I’m curious, why was that age of interest to you and Maya, who we should say plays Flannery in the movie?

Ethan Hawke: It was dictated to me. I mean, it was very obvious. You know, when Maya said, “Well, I’d like to play her,” Maya was 23. What was happening to Flannery O’Connor around the age of 23? Oh, she was diagnosed to die. That’s a pretty interesting time to set a biopic. Let’s zero in right on that moment.

ZD: What’s the drama in her life that’s expressing itself in her creative work?

Ethan Hawke: I was really hypnotized and moved by this very small transition that I thought was revelatory in her life. This was a young woman—she says over and over again in letters—the last place on planet Earth she wanted to be as a young woman was back in Milledgeville with her mother. We’re talking about the Jim Crow South. She was hell-bent to get out of there. It was a big deal to go to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. If you’re a lower middle-class Catholic girl from Milledgeville, Ga., that’s a heavy ask on your mother—you don’t have a father to pay for that school—to send your daughter north to get an education. But she was desperate for it. She was desperate not to go home.

She goes home to visit and gets diagnosed with the same disease that her father had, which her father died very quickly. So she felt death was imminent. And yet, if you go visit that farm in Milledgeville, [you can see that] she turned her writing desk away from the window and put it against the back of an armoire. And I found that wild, that somehow you could go from feeling trapped there to feeling like you don’t even need to look out the window, that you can bring the world to you. And I thought, that’s going to be the journey of the movie, is a spiritual and intellectual movement of the heart where you go from, not my will, but yours be done. And a full acceptance of that, and an embrace of the idea of the kingdom of God is in the midst of you.

AM: She wrote an article for America magazine back in the late 50s. And the main struggle there is this idea of being a fiction writer and a Catholic. There were some who doubted you could do that. Her response to that was she had to be a fiction writer first and live by the limitations of that craft in order to be a good Catholic. It was all about paying attention to reality as it is. And reality is often brutal and ugly, and there is sin, but there’s also grace. As you said, that’s hard enough to capture in writing when you’re trying to do it in a film. One way you do that is by interspersing little snippets of these short stories. I’m curious why you decided to do it like that and how you picked the stories.

Ethan Hawke: I felt that to understand her, you have to understand her work. There’s a line in the film from her journal: “I never completely lose myself unless I’m writing. And strangely, I’m never more myself than when I’m writing.” I came to the view that you could say, “I never completely lose myself unless I shed my ego. Strangely, I’m never more myself than when I shed my ego.” That our ego is in the way. She writes about this a lot, that our desires, our wants are often in the way of our ability to see grace because we have our own agenda with how the world is supposed to be working.

I thought to reveal a portrait of this woman, we have to show her work. To be intimate with her, you have to be intimate with this work. And I thought that film loves a relationship and the only relationship she really has besides with her Maker is with her mother. I looked for the stories where I found her exploring her relationship with her mother. I looked for stories where I saw Regina [Flannery’s mother] appearing. And once you read a couple of biographies, then you read the canon, I started seeing Regina in a lot of the stories.

Then I also saw the stories where there was a Flannery surrogate that she was using for self-discovery and a Regina surrogate. And those stories leaped to the front as the ones of what I was going to pick from. Interestingly enough, a lot of those stories, the great bulk of them that I used are from the end of her life. You can see a shift in her writing in the last six or seven stories. And we use a lot of those stories in the movie.

ZD: There’s something that’s very embodied about a lot of the stories that you chose that she’s writing about at the end of her life. We have artificial legs, we have bloody tattoos, missing arms. And Lupus; it’s debilitating to the body. And that feels to me like that has to come out of this sacramental imagination where the body is sacred and also this thing that can fail you. It’s this place where grace can happen but also deep wounds happen.

Ethan Hawke: There’s something about the body that’s so tactile. When you’re aware of it, you have an immediate knowledge of your mortality. It’s a reminder that it’s all a gift. The way that lupus manifests in her is she was constantly being given new diminishments—these things that she was not able to do anymore, whether it was eating salt or concentrating for more than X amount of hours, whether it was walking. Each one of these diminishments was also a teaching on gratitude for what she did have, what she did possess. Everything taken away was a realization of something that had been given.

The body is in a way our great teacher. For the over-50s, you know that as your face starts to crack and you’re being asked to go to another developmental place. You are constantly being asked to mature. And we often don’t want to. Grace requires change. It’s asking us for change and change is so difficult for us. It’s so difficult. We want to feel we have everything already, and it’s scary. And I feel like she uses the body as a constant reminder of our temporariness.

AM: That’s a good connection to a scene I want to talk about from the movie where there’s a dinner party; it’s Flannery and her classmates at Iowa Writers’ Workshop. One of the women is holding forth on faith and she describes the Eucharist as a symbol. And Flannery pipes in and says, “If it’s just a symbol to hell with it.” It’s this idea that the Eucharist, if it isn’t Christ’s body broken, then what’s the point? It’s a complex scene to try to depict on screen. What was your approach to it?

Ethan Hawke: It’s a complex idea, especially for non-Catholics. It’s hard to speak about because often when we speak about religion, a lot of people turn off because they get worried you have an agenda with their beliefs. It’s hard to engage in a dialogue, but as a person who has dedicated themselves to the arts, I used that Flannery line at the beginning of the film: “People see writing as an escape from reality; it’s not an escape from reality, it’s a plunge into reality.”

I feel that way about acting. When acting is good, it actually teaches me a lot about my real life, my daily life. When you can listen and be spontaneous and available and authentic as an actor, it helps you be authentic in your life because you start to teach your body how to listen and how to be present. And this point being that the imagination is real. This is a hard idea, in that Mass, it’s kind of an imaginative act. It’s almost like a theater piece. We’re imagining we’re witnessing the crucifixion. We’re imagining we’re witnessing this dinner. And it’s real. If we make it real, it’s not a symbol. It’s real, it’s really happening all around us all day.

You’re now deep inside my head, and it’s hard for me to communicate what I’m feeling to make it make sense to the listener of what it means to me. The central thesis of the film that I’m trying to show is that these events that people can call imagination or symbol actually change us. And if we absorb them, our hearts can be changed. You don’t come to that decision to turn your desk around and accept the situation you’ve been given without a lot of small changes in your heart. And those changes can happen through prayer, through imagination, through human creativity. The imagination isn’t just an escape. It’s how we are spoken to if we use contemplation correctly.

What’s the great Joan of Arc line about, she was on trial and one of the justices said to her, “Mademoiselle, you seem to be a victim of your imagination.” And she said, “How else would God speak to me?” I feel we all know this to be true, that things can’t get better if we can’t imagine them being better. The process of collective imagination is very, very powerful. That’s a central theme of “Wildcat,” whether we’re talking about Mass or whether we’re talking about writing, there’s something at work in what she is communicating to us about the power of prayer and imagination. Often they’re not as different as we might think.

ZD: You’re talking about change and conversion. I feel that for Flannery, these moments of grace or these opportunities for conversion almost always coincide with violence or something horrible or dramatic or shocking happening. I’m curious what your take is on Flannery’s view on suffering and its contribution to conversion. She has that follow-up line at the dinner about people thinking that religion is this warm blanket, but it’s the cross, which, of course, is God dying.

Ethan Hawke: The cross is a very, very powerful, dark symbol that a lot of us have gotten so used to seeing that we don’t contemplate the reality of what that symbol is expressing. I remember when I was younger being really blown away and moved when I was first trying to learn about Buddhism, and the first noble truth is that life is suffering. And I thought, well, isn’t that fascinating? Because when you think of Buddhism, often as a Westerner, you think of it as detachment, everything’s cool, everything’s fine. And no, the first truth is that life is suffering.

And I thought, wow, that’s the cross. That’s the first truth we’re being asked to look at as people raised in the Christian community—this is supposed to be hard. There is nothing wrong when your life is difficult. This is what we’re being asked to experience. Everything that’s born dies, everything. There’s not necessarily anything wrong with that.

I love that line of Flannery’s about the cross because we often want religion to be comforting like the choir, comforting like a Hallmark card or comforting like a sunrise. The sunrise is there every morning to comfort us. It’s there every single day. But there are other things at work, too, that we don’t need to hide from. If we just stay looking at the drawing of the sunrise or the beautiful baby, that’s comforting and nice, but that’s not all religion is asking us. It’s asking us how to live. And what she’s communicating is, yeah, in real life, people are criminals. People are crooks. People stab and murder one another. This is real, too. And God is there, too.

This is really difficult for our brains. But she’s using the short story, which is a very terrific medium for this because it’s not long-winded; you can read them in one sitting and they punch you in the face. She does things that are dangerous. It was dangerous for me to film her story “Revelation” where racist language comes out of the mouth of Jesus Christ of Nazareth. It’s a very incendiary thing to do. It’s clear to me that she’s talking about white supremacy masked in the cloaks of Christianity. It’s so obvious when you see it or read it in the story, how disturbing that is.

AM: One thing that she struggled with in her life and you portray in the film is that there wasn’t a huge audience, at least at that point, for the type of shocking and dark work she was doing. Her mom and her aunt are always asking her to write nice, cute stories, like Gone with the Wind. And she refuses to say that. You even relate it to the race question. One of her classmates tells her, you know, maybe don’t use the N-word in your writing, but both she and you decided to keep the harsh reality of language and of life in the South in your work. I’m curious how you came to that decision and what you learned from her unflinching look at reality.

Ethan Hawke: Well, she has that great line, “The truth doesn’t change according to your ability to stomach it.” It’s very difficult. America is difficult to write about. America is a racist country, and we’re submerged in it so deeply sometimes that it can be invisible to the white community, to the non-oppressed. And she was scouring herself, scouring the racist inclinations inside her own body and mind that she was watered and fed on this world. Her faith was forcing her to look at the hypocrisy in the community around her and inside herself.

Obviously, I’m really uncomfortable with it. I find the whole thing discomforting, but she’s forcing us to look at it and talk about it. I don’t suggest that I know some right way to behave, but I know that not talking about it doesn’t help. You can’t just ignore a wound and expect it to heal. There’s a great linea literature professor uses about Flannery that Flannery is like her country, a racist in recovery. We’re trying to figure out how to heal this great, horrible wound that’s been suffered. We didn’t create this country. And yet we’re forced to deal with her sins and forced to look at her future and how it could be better. I thought it was important to include that conversation because it’s a conversation that we’re scared to have publicly, but it happens in private all the time.

ZD: Ethan, I’m curious, between this film and some of your more recent work— I’m thinking of “First Reformed,”—you seem to be exploring more some religious questions at this intersection of faith and art. Is that true?

Ethan Hawke: It’s definitely true. There’s also “Good Lord Bird” where I played John Brown. And John Brown’s prayer was never ceasing. This is a man of deep faith and principle. These three works of mine exist in relation to each other. I doubt I would have made this film if I hadn’t made “First Reformed.” I was working on the writing of “Good Lord Bird” when I was making “First Reformed.” I don’t know if it’s turning 50. I don’t know if it’s the teachings of my childhood and my young adulthood bubbling up in me. I was asking and thinking a lot about this in my early 20s. And then I kind of put it aside in the pursuit of the performing arts.

I love being an actor, and I tried to direct all that faith and love and unanswerable questions toward “Before Sunrise,” toward “Before Sunset,” toward “Boyhood,” toward all the acting that I was doing. I did Shakespeare plays, and they all teach you things and they’re a place to put all that energy and questioning into the pursuit of substantive, meaningful art.

Then you turn about 50 and these people and these characters, the questions Flannery was asking or Reverend Toler in “First Reformed” or John Brown, I guess they’re just extremely interesting to me at this moment in my life.

AM: I’m curious how those questions and stories are received in Hollywood, which fairly or not is often seen from the outside as a kind of godless place. So what do you hear from fellow actors and directors?

Ethan Hawke: Well, look, God doesn’t sell, O.K.? If you want to disguise religion as a warm electric blanket you can sell that. But if you wanna sell a real conversation, you ain’t gonna sell it. You were talking earlier about those lines in the movie of Flannery’s mother saying, “Why don’t you write stories that people would like to read?” Often I felt that way about this movie. It’s like, why wouldn’t you make a movie that people would like to see? It’s a valuable question, but I believe that part of the responsibility of the artistic community is not just to have a nice conversation. We have some responsibility to help us have more difficult conversations. It’s nice to get a bedtime story, something to kind of take your brain away and relax your shoulders. I like that as much as anybody else, but I also think there’s a time for Emily Dickinson and there’s a time for Kierkegaard and there’s a time for Dostoevsky, and we’re indebted to these great minds of the past and we have a responsibility to try to pitch ourselves against the same challenges.

So it doesn’t sell, it’s difficult, but I know, [Zac], that you mentioned earlier when we were first meeting that you were a fan of “Before Sunrise,” and that movie didn’t sell either, but over time, you can find an audience. You can’t really reach them with a blitzkrieg of advertising, especially if no one will pay for it, but you can hope that through doing this podcast and through slowly people talking, I’m hopeful that people who are interested in Flannery will find a way to seek out this movie, and if they like it, they might tell their friends about it. That may take 25 years, but as Flannery said, I believe love to be efficacious in the long run.