A Homily for the Sixteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time

Readings: Jeremiah 23:1-6 Ephesians 2:13-18 Mark 6:30-34

Before Downton Abbey there was Upstairs, Downstairs, and before both, there was Brideshead Revisited. The latter has been twice adapted for film, but it began its life as a great work of literature with a cameo appearance of the Blessed Sacrament.

While a student at Oxford, Charles Ryder falls in love with a teddy-bear-toting, champagne-and-strawberry-swilling Sebastian Flyte. Sebastian invites Charles home to the Brideshead estate, where he meets Lady Marchmain. She is the strident and estranged wife of Lord Marchmain, who has abandoned his wife, family and faith for a mistress and the life of an expatriate in Venice.

Charles also meets Sebastian’s siblings, Bridey, the boring and somewhat buffoonish first son; young Cordelia, who eventually goes off to fight in the Spanish Civil War; and the beautiful Julia. Charles falls in love with her as well but with no more success than he had with Sebastian.

Charles was raised without religion. The Flyte family is Catholic, though—as it often is—the matter is complicated. Here is how Sebastian sums it up for Charles:

So, you see, we’re a mixed family religiously. Brideshead and Cordelia are both fervent Catholics; he’s miserable, she’s bird-happy. Julia and I are half-heathen; I am happy, I rather think Julia isn’t; Mummy is popularly believed to be a saint and Papa is excommunicated—and I wouldn’t know which of them was happy. Anyway, however you look at it, happiness doesn’t seem to have much to do with it, and that’s all I want…. I wish I liked Catholics more.

The deathbed return of Lord Marchmain to the Catholic faith is the climax of the novel, but another beautiful passage comes at its close. The Second World War has erupted, and the Flyte family is now dispersed. The Brideshead estate has been transformed into an army camp. Captain Charles Ryder is among the soldiers stationed there.

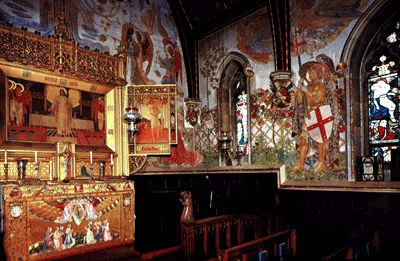

There was one part of the house I had not yet visited, and I went there now. The chapel showed no ill-effects of its long neglect; the art-nouveau paint was as fresh and bright as ever; the art-nouveau lamp burned once more before the altar. I said a prayer, an ancient, newly learned form of words, and left, turning towards the camp; and as I walked back, and the cookhouse bugle sounded ahead of me, I thought:—

Charles steps back from remembering all the struggle and hope he had known in this house. Now, in the light of his own conversion to Catholicism, he considers the centuries this home has stood. Surely more than one drama has been played out here by those ignorant of God’s presence among them, God’s work in their lives.

The builders did not know the uses to which their work would descend; they made a house with the stones of the old castle; year by year, generation after generation, they enriched and extended it; year by year the great harvest of timber in the park grew to ripeness; until, in sudden frost…the place was desolate and the work all brought to nothing; Quomodo sedet sola civitas. Vanity of vanities, all is vanity.

And then comes the novel’s close. Nothing more about the family or their struggles to find happiness apart from the faith, with the faith or in ignorance of the faith. Only this paragraph in which God, the unseen conductor of this exuberant yet sad symphony, takes a bow.

Something quite remote from anything the builders intended has come out of their work, and out of the fierce little human tragedy in which I played; something none of us thought about at the time: a small red flame—a beaten-copper lamp of deplorable design, relit before the beaten-copper doors of a tabernacle; the flame which the old knights saw from their tombs, which they saw put out; the flame burns again for other soldiers, far from home, farther, in heart, than Acre or Jerusalem. It could not have been lit but for the builders and the tragedians, and there I found it this morning, burning anew among the old stones.

This week the U.S. church gathers in Indianapolis for the Eucharistic Congress. Its purpose is to ponder the mystery of Christ present to us in the Eucharist. That presence is first and foremost in the mystery of the Mass, where, as the Second Vatican Council taught us, Christ is truly present in five distinct ways:

To accomplish so great a work, Christ is always present in His Church, especially in her liturgical celebrations. He is present in the sacrifice of the Mass, not only [1] in the person of His minister, “the same now offering, through the ministry of priests, who formerly offered himself on the cross,” but [2] especially under the Eucharistic species. By His power He is [3] present in the sacraments, so that when a man baptizes it is really Christ Himself who baptizes. He is [4] present in His word, since it is He Himself who speaks when the holy scriptures are read in the Church. He is present, lastly, [5] when the Church prays and sings, for He promised: “Where two or three are gathered together in my name, there am I in the midst of them” (Mt. 18:20) (Constitution on the Divine Liturgy, “Sacrosanctum Concilium,” §7).

Most of us are what we are when it comes to matters of faith. We tend to “dance with the one who brung us.” But I like to think that if I had not been born and raised Catholic, the church’s insistence on the abiding presence of Christ in the Eucharist would be enough to call me home.

The church first retained the eucharistic elements after the Mass had ended so that they could be brought to the sick. The thinking was that if Christ had given himself completely in the celebration of the Eucharist, he would surely give himself to those unable to come. Hence his presence remained in the consecrated elements.

But if Christ was truly present in them—and everyone agreed that he was—then he was sacramentally present whenever anyone approached those elements, housed in what came to be called a tabernacle, after the Tent of Meeting in the Old Testament, the one containing the Ark of the Covenant.

Such a silent presence of Christ, yet so surely does he act therein! How many times was I ready to leave the seminary but, after an hour in front of the Blessed Sacrament, could not? How many times have I entered a Catholic Church, at an obscure hour of a weekday—when others are locked—to find Catholics abiding with their Lord, who promised to be there for them? How many candles have been lit before this presence, insisting that, like the candle, the one seeking God would have wished to remain here, faithful and present, as Christ himself does?

If you have never prayed alone in front of the Blessed Sacrament for more than a few moments, have you ever fully known the Catholic faith? From Jeremiah:

I myself will gather the remnant of my flock

from all the lands to which I have driven them

and bring them back to their meadow;

there they shall increase and multiply (23:3).

In a quiet meadow, God gathers what we have scattered.

This great promise is fulfilled in the Son. “People were coming and going in great numbers” when the Lord said to the disciples whom he had chosen: “Come away by yourselves to a deserted place and rest a while” (Mk 6:31). The place was to be silent. A place of solitude. But they would not be alone. He would be with them, giving himself to them, abiding with them.

“The flame which the old knights saw from their tombs…I found it this morning, burning anew among the old stones.” The genius of the faith! To know that what Christ once did in the Scriptures he continues to do each day, in nigh every place in the world.