August in the California high desert is covered by a cloud of dust, and everything seems to wither under the triple-digit temperatures without a cloud in the sky. Yet there we were, over 100 people from Catholic parishes, some coming from nearby, others having driven for hours, all standing together under the blazing sun.

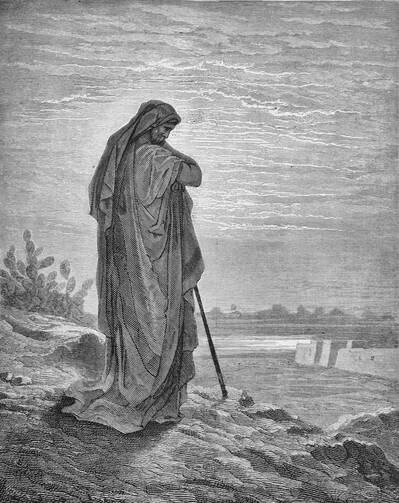

My mind has often returned to that day in 2019 because it was then that I finally understood the biblical prophets.

This particular desert, just northeast of the picturesque Angeles National Forest, has many similarities to the deserts of the Middle East where our faith ancestors lived. In both places, everything is stripped bare, and water and shade are truly miraculous. On that day etched in my memory, the mothers pushing strollers, the abuelas relying on the steadiness of their canes, the teenagers hoisting high their signs of hope, the parish folks who knew each other, and those meeting for the first time were all there for the same reason.

An infamous prison called Adelanto—named for the nearby town (which, paradoxically, means “progress”)—had been transformed into a for-profit “detention center” filled with terrified immigrants. We were there to offer support to the incarcerated, to listen to the testimonios of their grief-stricken children and families and, most important, to pray together in the conviction that our God hears the voices of the suffering and those who intercede for them.

As we assembled, the guards told us that our efforts would be restricted to the other side of the road from the detention center, dashing our hopes that the interned migrants and asylum seekers would be able to hear the community singing hymns of consolation from our shared faith. Adding to our distress was the fact that a group of five anti-immigrant protesters had not been subject to the same restrictions and were allowed to set up multiple metal stands with large flags and signs right in front of the entrance to the detention center. Not just that, but each of them was equipped with a bullhorn that could mimic the sound of police sirens, as well as amplify their voices.

As our attempt at a prayer vigil began, the stories of the children of the detained were mercilessly drowned out by the blaring sirens. To make their antagonism even more explicit, the anti-immigrant protesters kept up a constant stream of verbal attacks demonizing those they had labeled “illegals” and those of us who dared to support them. It soon became clear that even our efforts to comfort or to pray would go unheard.

At that moment the tragic absurdity of it all overcame me. How was it possible that an aggressive group of five could overwhelm a peaceful community of 100? How could it be that voices in prayer were drowned out by insults? How heartbreaking was it that those inside would hear the shrieking, simulated police sirens instead of our songs? It was then I realized that the goal of the anti-immigrant protesters was in large part to cause despair: They hoped that the incarcerated and those who loved them would simply give up, put down our heads in submission and accept the inevitable. The restrictions, the pitiless interference, the invectives, made it so we felt completely powerless and crushed by a world that did not recognize the people inside the detention center as human beings and extended that indiscriminate dehumanization to everyone who supported them.

It was then that a great appreciation for the prophets welled up in me. Suddenly, the distance of time between them and us disappeared. We raised our eyes, arms and voices in plaintive supplication for God’s mercy to rain down upon us while parishioners held up a banner proclaiming, “Love your neighbor as yourself” (Mk 12:31). No, we were not going “back to where we came from,” as the protesters repeatedly commanded us to do. We were staying right there because God was present with us at that moment and in that place.

I learned something crucial that day: When we are truly attentive to the reality of human suffering, the Spirit will move us to a different kind of prayer defined by an unmistakable sense of our radical dependence on God. In the abyss, the light of God became brighter. Situations like what we were experiencing in Adelanto made it clear that a faith that does justice is not an abstract concept. It is made most present in the crucible of real life, and it demands we respond by turning to God.

The connection I felt to the biblical prophets that day prompted another question in me: What does it mean to be prophetic today? What can we learn from the lives of the biblical prophets that can direct us in the 21st century? A look at this question through the specificity of that day in the desert may help to guide us. Here are five qualities that today’s prophetic voices share with our biblical predecessors.

Attentive Unveiling. One of the most difficult things biblical prophets were called to do was to help their communities see with clarity those things that were contrary to God’s will. For this, they had to incessantly call their contemporaries to attentiveness. Sinfulness, they came to realize, did not always go around announcing itself. No, the denial of the vision of God was often concealed and had to be called out forcefully by the prophet. Over 700 years before Jesus would walk the same roads, the prophet Amos saw this and decided to go for broke. His piercing words, which even today sound like they could bring down mountains, sought to wake up his community.

He cries out, “Prepare to meet your God!” (Amos 4:12). And in between his announcements of the punishments that will come from God’s hand, the prophet makes clear the kind of human acts that offend God. His contemporaries have exiled whole populations, they have denied their kinship (1:6, 9) and they have used weapons and violence especially against women and children for the purpose of profit and obtaining more land. More explicitly, he tells them they have done this by “suppressing all pity” (1:11). Like his fellow prophet Isaiah, Amos makes clear that God’s will is often obscured by lies (2:4).

Explicit Measuring. But what is God’s will? Once aware of God’s indignation, the prophet makes plain the chasm between what God demands of us and what we are doing. In other words, those gathered in front of the prison on that day were there because the mistreatment of immigrants in our country needed to be exposed precisely as an offense against God. In these hyperpartisan times, it is good to remember the words of Martin Luther King Jr.: “a just law is a [human-]made code that squares with the moral law or the law of God.” Dr. King questioned those Christians who conveniently turned the other way in the face of dehumanizing segregation and racism, asking poignantly, “Who is their God?”

For his part, Amos was eloquent as he asked how it was possible that people would willingly “hand over the just for silver, and the poor for a pair of sandals” (2:6). We must ask ourselves: How often do we get caught up in lies that deny the higher law and obscure our lack of pity for the desperate poor?

Redemptive Protagonists. Many moments in history present us with a choice, and the prophetic act is precisely about embodying our choices. The prophets were clear that it was the deeds of human beings “turn[ing] justice into wormwood and cast[ing] righteousness to the ground” (5:7) that they were denouncing. Yet those same humans participating in these offenses could choose otherwise and become protagonists for justice and collaborate in God’s redemptive desire for creation. To be protagonists, actors in a just world, means to “seek good and not evil” (5:14), to “let justice prevail at the gate” (5:15), and to “let justice surge like waters, and righteousness like an unfailing stream” (5:24).

Amos warned against the complacency of empty offerings and rituals (5:21-23), and he was to be echoed repeatedly centuries later by Jesus. In our own day, the elderly, the mothers and the children gathered at Adelanto felt the power of prayer deep in their bones, a power that turned them from victims to compassionate voices. As they purposefully entered into solidarity with the incarcerated, they discovered the Spirit’s promptings and trusted in the ultimate goodness of God. What did those busy drowning their voices with accusations feel at those same moments? Might they have gone home that night with the memory of someone’s tear-filled eyes still lingering? Might that memory of the suffering just transform them?

Cosmic Power. While it was the particularity of what was happening in Adelanto that called us there, the prophets teach us that God is God of the entire cosmos. As Amos describes it, our God is “the one who forms mountains and creates winds, and declares to mortals their thoughts; who makes dawn into darkness and strides upon the heights of the earth” (4:13). Such a view of God’s sovereign power—as the one who comes to the aid of the helpless—is fundamental to Christian faith. Confronted by those who think they are powerful because they can judge others and imprison them, prophets cry out for heaven’s ultimate power on behalf of the powerless.

Is anti-immigrant sentiment dependent on fundamentally flawed understandings? Do those who advocate separating families because of immigration status not realize that their perceived power is temporary and ultimately contingent on a situation? Might they eventually see that they are in fact usurping the power of God in an act of flagrant disobedience to the inviolable command to love one another?

Unbreakable Justice. The justification to treat others with cruelty over some perceived transgression depends on separating reality into two realms. Years ago, while working at the Franciscan Communications Center in Los Angeles, I found in their archives a television public service announcement from the 1960s, in which the Franciscans prophetically exposed this inconsistency. As I recall, the ad featured a white family making its way toward a church dressed in their Sunday best, while conspicuously avoiding a Black family and an Asian family. The voice-over simply stated, “If you can’t find God out there, you won’t find God in here.” Defining one’s claim to a superior faith by separating “the sacred” from “the secular” sets up a permission structure that says, “As long as you’re praying individually and spending a requisite time inside the church or temple, then you’re good with God.”

The prophets, on the other hand, stressed the opposite: All of reality is sacred and God’s grace cannot be contained. A repeated theme in Scripture is that the one acting justly often does not come from the ranks of the outwardly pious. Think of the searing indictment of Jesus’ prophetic parable of the good Samaritan (Lk 10:29-37), where both the priest and the Levite (also a key person for worship) avoid the injured man, leaving him to die.

It is the Samaritan traveler, an outsider to their exclusive circle of the righteous, who is “moved with compassion” and cares for the victim. That most sacred act of saving someone’s life is performed out on a road; its protagonist is an outsider; and Jesus, the prophet, calls attention here and in many other places to the unbreakable unity of all reality. In Jesus, the lilies are sacred, the waters are sacred, the lepers are sacred, and those who have sinned are forgiven because they are sacred. The community praying out on a dusty desert road was making present God’s ultimate love for all God has made. In the scorching words of the prophets as they railed against the powers who trampled the weak, we can hear the promise of a different world.

We left the desert that day exhausted, covered in dust but also prayerful. God’s love, present in the many who showed up that day, was visible, abundant, resilient and hopeful. In Adelanto, the hard work of being prophets became real and the world’s sacredness surrounded us. The most repeated command in all of Scripture is:Do not be afraid. Violence needs our fear to stoke it, but nonviolence flowers and overflows when we allow our broken hearts to feel God’s generous accompaniment calling each of us by name. Will we answer?