In his 38 brief but busy years, Stanislaw Wyspianski (1869-1907) became a 19th-century cultural giant. He is to Krakow what Henrik Ibsen is to Oslo or James Joyce is to Dublin. Yet largely as a result of the isolation imposed on Poland, which for decades was hidden behind the Iron Curtain, few in the United States know his name or his work.

An artist, playwright, designer, poet and dabbler in architectural restoration and opera librettos, Wyspianski gained stature as a public intellectual throughout Europe during the time of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He exhibited his paintings in Munich, a European art center linked to the burgeoning Viennese Secession movement started by Gustav Klimt and other artists, of which Wyspianski was an early member.

His graphic legacy is visible throughout Krakow today: in the unique floral and geometrical murals painted on the interior of the Church of St. Francis of Assisi; in the stained glass windows there and in three windows he designed for Wawel Cathedral but which were not executed until a century after his death; and in his collected works, which fill a museum named for him that is a branch of the National Museum in Krakow.

A Public Intellectual

As a dramatist, Wyspianski (pronounced Vispee-AN-skee) not only wrote groundbreaking plays but also designed the stage sets, furnishings and costumes. “The Wedding” (“Wesele”), his play about class-consciousness and class conflict, brought him lasting fame and stature in the theater. It is considered by many to be the best Polish drama of the turn of the century. The plot draws “a bitter picture of the powerlessness of a society that was triply fettered: by the political regime, by the inert national tradition and by the skepticism of its intelligentsia,” writes the art historian Marta Romanowska. Some of those same social forces, particularly the foreign occupation and the Marxist goal of a “classless society,” gave this play new life during the Communist takeover of Poland. In 1972 “The Wedding” was made into a film by Andrzej Wajda, an Oscar-winning director. (An English translation of the script is available.)

The artist was born in Krakow. After his mother died when he was 7 and his father, a sculptor with an alcohol problem, proved unable to care for him, the young Stanislaw was raised by an aunt and uncle. He received a classical education in ancient history and mythology and learned Polish folklore and history—all of which informed his adult creative work. He illustrated The Iliad, for example, and wrote a historical epic about the Polish king Casimir the Great; he also created major stained glass windows: “Apollo: the Copernicus Solar System,” “God the Father” and “Polonia,” the widowed queen Mother of Poland, who symbolized the nation itself.

Wyspianski entered adulthood at an auspicious time. After graduating from Jagiellonian University and the School of Fine Arts in Krakow, where he was later asked to join the faculty, the young artist traveled through the Hapsburg Empire on a grant. Later he rambled across Europe, taking in the momentous developments in fin-de-siècle art, architecture, music and literature. Remembered bits of what he had seen would soon reappear in his own modernist/neo-romantic style. In Paris, Wyspianski studied painting in one of the many ateliers that surrounded the école des Beaux Arts and visited galleries with Paul Gauguin before the Frenchman left for French Polynesia, where he died. Wyspianski showcased the best of Polish culture, while bringing it into the modern world.

In 1905 Wyspianski was elected to the Krakow City Council, despite a conflict with the Krakow Theater that caused him to ban temporarily the staging of his works. He died two years later of syphilis. At the time there was no cure for syphilis, called “the French disease,” which blinded Degas and afflicted Gauguin, Manet, Van Gogh and Toulouse Lautrec, among thousands of others. Unlike any of these artists, however, Wyspianski, who was recognized in Poland as a cultural light now extinguished, received a hero’s burial.

Soon after, a critical edition of his works was compiled. Collec-tions of his writings, art and letters have been published and translated. Many contemporary graphic artists cite Wyspianski’s paintings as a major influence on their work. Modern playwrights and producers cite Wyspianski’s dynamic scripts and stagecraft as a model. His legacy touched at least one pope. The young Karol Wojtyla (Pope John Paul II), as a student at Jagiellonian University, studied Wyspianski’s writings and as an actor played the leading role in a production of “The Wedding.”

The Artist at Home

For a glimpse into the personal life and sensibility of this very public figure, consider the artist’s pastels, which include landscapes, self-portraits and portraits of friends and family. The drawings and paintings of his wife and children reveal a tender side of the artist’s personality and rank among his best-known and best-loved works. Many of these were on view in the Planty, a park that rings the Old Town of Krakow, when I visited in 2007 and saw them as part of the city’s centenary celebration of Wyspianski’s death. Completely taken by their loveliness, I spent an entire day in the Wyspianski Museum, which is housed in a former palace. Since these informal, mostly small and intimate works served as my initial introduction to the artist, I thought they might well do the same for others.

In 1900 Wyspianski married Teodora Pytko, an uneducated peasant employed as his aunt’s servant, and they had four children: two sons (Stas and Mietek) and two daughters (Elizy and Helenka). These children were still young when Wyspianski died in 1907.

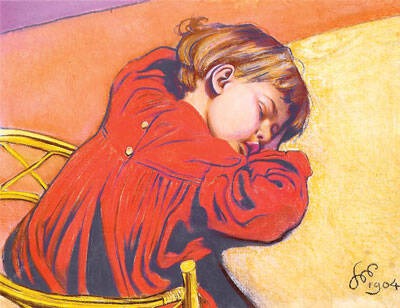

In these pastels one sees the artist’s quick hand, attention to natural poses, imaginative use of color and flair for the drama of daily life. (He used pastel, polychrome and stained glass because he was allergic to oil paint.) His daughters peer at their infant brother, who is nursing at their mother’s breast; children fall asleep with complete abandon wherever they happen to be or gaze at the viewer with fingers in their mouths or with gaping expressions of wide-eyed wonder. In one portrait, Helenka exudes a half-asleep bleariness, oblivious to her own tousled hair; in another she reaches out to touch a vase of flowers.

These family pictures and works showing other children compare well with similar works by Wyspianski’s peers. In Mary Cassatt’s Impressionist drawings, formal etchings and oil paintings of children, many of the subjects were her own nieces and nephews or children of friends, relationships that seem to have deepened their appeal to her and, hence, to the viewer. John Singer Sargent’s portraits of children, with and without their well-heeled parents, were mostly paid commissions, yet his work also shows a quick eye and brush as he catches the innocence and elegance of his subjects. Edgar Degas painted teenage ballerinas at rehearsal, backstage or onstage. When he captured their unguarded expressions, his pictures convey a certain sadness or fatigue; these are working girls.

By contrast, in Wyspianski’s portraits one finds impish faces beneath hats, tots lost in thought, youngsters embracing one another in childhood friendships. While there may be a bit of Norman Rockwell in one or two, I find refreshing the lack of tacked-on “cuteness.” These children are presented as fully formed, with God-given dignity and grace, which gives the images authenticity. Real children have contemplative moods, compassion, intelligence, curiosity, longings, angst; even their trusting presence is worthy of respect. As both an artist and a father, Wyspianski had the humility to study children and learn from them. Later he incorporated these observations into the young people he depicted in his monumental and formal stained glass windows.

At times Wyspianski presents his soft-bodied, square-faced wife as a Madonna or earth mother surrounded by children; several of these paintings he titles “Maternity” or “Motherhood.” I am heartened that he painted himself into joint portraits with his wife, that he was not only an artist-observer but a participating husband and parent. He saw family, and each family member, as deserving of his time and creativity, even when the works were not made to be sold but were for himself and for them. The artist’s positive attitudes about family and the importance of children gives these works a spiritual centeredness. The depth of character he observes and the beauty he communicates give them soul.

Stanislaw Wyspianski, whose dynamic inner life once helped to fuel the cultural life of Poland and still infuses its cultural history with genius and dignity, was grounded in the private, personal world of family. The home, its living spaces peopled by children, served as the studio where he transformed his observations of family life into works of art with universal appeal.

Watch Karen Smith's video analysis of Wyspianki's "Self Portrait."