The data just keeps piling up. Since the 2008 U.S. Religious Landscape Survey from the Pew Forum on Religion in Public Life first noted a substantial increase in the number of Americans reporting no religious affiliation, report after report has confirmed what religious leaders outside the evangelical resurgence of the 1980s had known for some time: checking “no religion” is increasingly normal in the United States.

Following the report in 2008 of a doubling in the percentage of so-called nones, from a mere 7 percent in 1990 to more than 15 percent in 2008, Pew’s 2012 “‘Nones’ on the Rise” survey tracked further and more rapid growth in the number of unaffiliated. One in five Americans told researchers they had no religious affiliation, an increase of 30 percent in only four years. In April of this year, a new Pew report projected that nones would make up more than a quarter of the U.S. population by 2050. Count those as the good old days of growing unaffiliation. The latest Pew research, published in May, shows that nones are closing in faster than anticipated. The new numbers show that between 2007 and 2014, nones grew to nearly 23 percent of the U.S. population. Among Americans under age 30, the percentage of nones has jumped to nearly 40 percent. At the same time, Roman Catholic affiliation has dropped from 24 percent in 2007 to 21 percent in 2014, and mainline Protestant affiliation has ticked downward from 18 percent to below 15 percent of the U.S. population.

What is the bottom line? It would seem to be that the United States will remain at least nominally a “Christian nation” for some time into the future. But the role and influence of Christianity in U.S. culture will certainly change as more people set aside spiritual and religious pursuits entirely or undertake them primarily outside of institutional religious settings.

Some of the effects of the decentering of religion in general and Christianity in particular are easily recognizable. In the political arena, for instance, religious background is less and less important. Indeed, Mayor Bill de Blasio of New York City has highlighted his spiritual-but-not-religious self-identification as a credential for working effectively with diverse religious groups as well as those not affiliated with institutional religions. Where being unreligious was once a political liability, in some political races being too religious can now be problematic. Similar shifts in the role of religion in culture have been playing out for decades in education, health care and popular media. But more subtle transitions are also under way, those associated with how religious idioms—symbols, rituals, artifacts, doctrines, holy figures, turns of phrase and, by no means least, sacred stories—circulate in the wider culture. It is here that what might be called the none-ing of the United States will likely have its most pervasive and enduring effects on ways of perceiving, interpreting and expressing our experiences of reality, which have for centuries been shaped extensively by Christian ideas and practices. The wellspring of Christian idioms is, of course, Scripture; and we can fairly wonder if and how the growing population of nones might continue to engage Scripture and how this might change Scripture itself.

Over the past three years, as I have interviewed different kinds of nones across the United States—atheists, agnostics, secular humanists, spiritual-but-not-religious, spiritual and sundry other sorts who identify religiously as “nothing-in-particular” or “all of the above”—about their spiritual lives, I have been surprised again and again by the degree to which many of the unaffiliated continue to find Scripture—especially the parables of Jesus—spiritually meaningful and morally relevant. My conversations with nones have likewise revealed a somewhat different emphasis in their engagement with Scripture than is often seen among the churchgoing set. I will turn to that shortly. But first, it is worth considering how nones find their way to Scripture in the first place. After all, aren’t nones unrepentant unbelievers with Bill Maher-like hostility toward the church and all its practices? Not so fast.

Liminal Christianity

For all the (digital) ink spilled in the coverage of nones over the past couple of years, there are some complexities in the data on nones that are often missed in both public reporting and religious handwringing about the “decline of religion in America.” First, we should bear in mind that the majority of nones—nearly 70 percent in the 2012 Pew data—report that they believe in God, a higher power or a transcendent life force of one sort or another. A scant 3 percent of the population identify as atheists, the proportion of the unaffiliated that has grown the least since 2007.

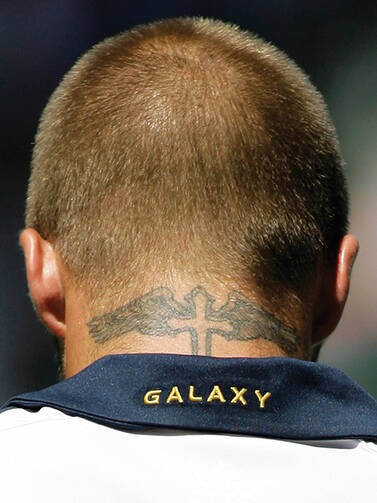

Furthermore, given the longstanding Christianized culture of the United States, it should be no surprise that the majority of nones come from an at least nominally Christian background. Christianity is very much the framework for American “civil religion,” and its more or less subtle influences are found everywhere from sporting events to the “Real Housewives of New Jersey” to Lady Gaga videos. One would have to be more resolutely unplugged than unreligious to escape the circulation of Christian idioms in the culture. Given the Christian background (however slight) of many nones and Christianity’s continuing influence (however much it might be waning) in the wider culture, we find what might be described as “feral” Christians of a sort—undomesticated religiously by regular church experience but more than happy to lap from time to time from a saucer of spiritual sustenance set out in the churchyard. The “‘Nones’ on the Rise” survey stirred the anxieties of religious leaders when it reported that among the religiously unaffiliated only one in 10 is “looking for a religion that would be right for you.” But here the humble “a” in Pew’s survey question hits far above its typographic weight. No, most of the unaffiliated are not looking for a single religious group to call their spiritual home till kingdom come. But some, earlier research from Pew revealed, are engaging multiple religious traditions, often quite actively and with sustained congregational participation, without necessarily becoming members or identifying with that tradition.

I think of these nones as the “free-range faithful,” ambling all about the religious landscape to partake of its diverse offerings without seeking a single set of answers (or questions) or intending to settle in one spiritual place. The journey, as the saying goes, is the destination. Or, as a 33-year-old none from Waimea, Hawaii, told me, “There’s something about selecting one religion, one path, in the narrow way that I was brought up that seems so wrong, so unhelpful. The world is filled with wisdom. Human history is filled with wisdom. Why would I close myself off to that?”

Finally, religiously unaffiliated nones continue to interact with “somes,” as I have come to call the religiously affiliated, in everyday life as family members, friends, colleagues, customers, neighbors and so on. They gather over holiday dinners and at weddings, baptisms and funerals regardless of their differences in beliefs and practice. However muted by social norms that restrict the discussion of religious perspectives, nones and somes share many religious and spiritual experiences, many of them shaped by expressly Christian traditions.

The religious engagement of nones and somes unfolds, then, in the rich in-between of everyday life, in their shared spiritual experiences—however differently they might interpret them. This mutually influencing interaction creates a liminal religiosity that I consider the defining character of religion in the United States today. It is widely distributed rather than congregationally confined. It is relational and experiential, oriented toward being present to the spiritual based in the self, the other and the world instead of in structures of belief, belonging and behaving associated with traditional religions.

All this makes clear that the unaffiliated should hardly be considered wholly unreligious, even if their religiosity plays out largely beyond the doors of the neighborhood church. Further, we cannot assume that nones are any less steeped in Christian traditions than are Catholic or Protestant somes. Indeed, many of the more than 100 nones across the country I have interviewed over the past three years were deeply conversant with Christian traditions, especially Scripture. What is more, regardless of where they fell on an atheist-to-spiritual continuum, the nones who talked with me often retained considerable regard for the Christian Scriptures, especially the teachings of Jesus in the New Testament.

Good Samaritan or Golden Rule?

Nones’ regard for the Jesus of the Gospels has nothing to do with doctrinal beliefs about the divinity of Jesus, his status as the Son of God or the promised Messiah or his resurrection from the dead. For the nones for whom Jesus remains a meaningful spiritual figure, stories of his healings, his embrace of social outcasts and his critiques of religious hypocrisy and government-sponsored violence and injustice mark Jesus as a moral and spiritual exemplar.

A 30-year-old none who was raised in a conservative Presbyterian family in San Antonio, Tex., insisted: “Being an atheist doesn’t mean I hate Jesus. You have to love the whole good Samaritan story, or the way he stood up for the adultery woman. You don’t want to throw that away, because we need those stories.”

“When you let go of the idea that all of the so-called facts of the Bible have to be quote-unquote true with a capital T—when you just treat them like important ancient teachings like, I don’t know, The Odyssey,” a 55-year-old secular humanist from Boston told me, “then you can really get to understand why Jesus has been such an enduring spiritual figure. I mean, there is real truth in a lot of these stories—as there is in other ancient myths. I don’t have to either dismiss all of that because I’m a humanist or believe in Catholic doctrine on the virgin birth to have it make sense.”

A 28-year-old agnostic from Oakland, Calif., also shared with me her appreciation for the parable of the good Samaritan:

I just was always inspired by that story ever since I was little. You know, that we could be that way toward each other. It’s really the ideal for me of how people should behave. Not “do unto others,” but more like “do what they need when you find them on the road.” That still really matters to me even though I don’t think of myself as a “Christian” in a religious sense anymore. Spiritually, though, I guess I still have that in my personal beliefs—that this was what Jesus stood for and expected us to emulate.

Among the nones who talked with me, the person of Jesus and the Bible came up regularly when I asked about spiritual influences. These nones tended to highlight the humanity of Jesus and his social action over his divinity or his miracles. A 19-year-old none from Marietta, Ga., who was actively involved in efforts to develop clean water sources in drought-affected regions of Africa, put it this way: “I don’t need ‘magic trick Jesus.’ I’m not interested in that, and I’m not interested in ‘saving my soul.’ I’m not about saving myself. I want to save the world.”

In this regard, the nones I spoke with differed from the “Golden Rule Christians”—practicing believers across Christian denominations and ideological spectrums who take as the core Christian value the scriptural teaching that one should “do unto others as you would have them do to you” (Mt 7:12). The sociologist Nancy Ammerman, in Lived Religion in America, describes these mostly suburban, middle-class Christians in her research this way: Most important to Golden Rule Christians is care for relationships, doing good deeds, and looking for opportunities to provide care and comfort for people in need. Their goal is neither changing another’s beliefs nor changing the whole political system. They would like the world to be a bit better for their having inhabited it, but they harbor no dreams of grand revolutions…. The emphasis on relationships among Golden Rule Christians begins with care for friends, family, neighborhood, and congregation.

Professor Ammerman points out that Golden Rule Christians, not unlike good Samaritan nones, are largely uninterested in theological doctrines and debates, focusing instead on the practices of congregational communities. She suggests, however, that Golden Rule ethics practiced by congregationally affiliated Christians invite “a certain narrowing of the circle of care” that can prevent serious or sustained engagement with larger, more distant or distributed problems in the world. At the same time, this parochialism can also ensure a deeper level of care for the most vulnerable in a local community, like the elderly, the sick or children. Such practices, on the one hand, help to sustain existing congregational communities. On the other hand, Golden Rule Christians may hesitate to reach out much beyond their narrow circles of care.

The difference here is subtle but significant: Nones who engage Scripture tend to do so by way of inspiring cosmopolitan rather than communitarian action. The starting point for engagement is a recognition of otherness rather than a reinforcement of commonalities. It is about receptivity to difference rather than reinforcing community on the basis of similarity.

Now, this Good Samaritan ethic hardly requires a radical re-reading of Scripture in light of some new assessment of Christian values. But it does insist, as Pope Francis seems to be doing to great spiritual if not affiliational effect, that the realm of religion, faith, spirituality, moral action—all those things that used to be seen as the exclusive purview of institutional religions—begins outside the doors of the church rather than inside. Open the doors, nones seem to be saying in their reading of Scripture, and see all the people.