Beginning in December with Jim Martin’s book, Jesus: A Pilgrimage, the Catholic Book Club at America will read and discuss recently published books on the person of Jesus Christ. The Book Club will consider a wide spectrum of perspectives that speculate on the historical Jesus in light of Scripture. We will discuss the following books:

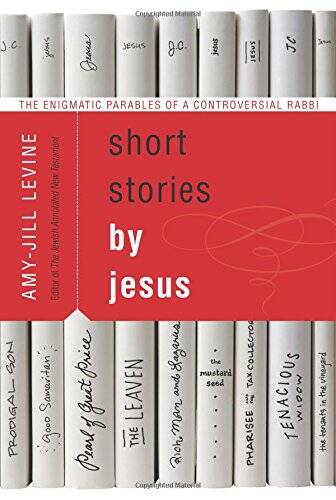

Prof. Levine’s book should do just that. She is a professor of New Testament and Jewish Studies at Vanderbilt University. In her book, Short Stories by Jesus, she considers several of Jesus’ parables and ponders how they would have sounded to Jesus’ original audience, first-century Galilean Jews. As I read Levine, an image continued to arise in my mind that illustrates the basic orientation of Levine’s work. Some years ago, the Gesu, the Society of Jesus’ mother church in Rome, underwent a renovation. In the process, one of the most sacred images of Mary and Jesus, which predates the Jesuit church, was restored. As artists began cleaning the image, they realized that the elaborate crown and jewels on Mary and Jesus were much later editions. The artists stripped away the added bling and a poignant, more ancient image of Madonna and child emerged. In a sense, this is exactly what Prof. Levine attempts to do with the Jesus’ parables. She strips away layers of meaning added to the stories by centuries of Christian interpreters in order to help modern readers contemplate Jesus’ parables as they might have been heard by the original audience.

Levine’s analysis carefully reveals layers of anti-Judaism that have accumulated through the long history of Christian consideration of these rich stories. First, Levine identifies parables as stories containing a surplus of meaning. They are meant not for decoding but for provoking thought about righteousness living. Ultimately, the meaning of each parable remains un-fixed and open to generations of readers. Second, parables are not allegories, that is, they need no element outside the parables themselves for the parable to be understood. This is an interesting claim. In interpreting Matthew 20:1-16, the Laborers in the Vineyard, Levine writes that many readers and preachers take up “the easy allegory that the landowner is God, and the parable becomes how we are to understand the divine. Once allegory enters, the real world is left behind, as well as any concern the parable—and Jesus, its teller—might have for issues of economics, employment, and the relationship between managers and employees” (199). Indeed, as Christians believe that Jesus is the manifestation of God, they are hungry to hear Jesus describe the Triune God to them. Perhaps this parable and others are more directed to human ethical relationships. In summarizing several parables, including the Laborers in the Vineyard, Levine writes:

In this interpretation, Levine strips away the notion that the last to be hired for the vineyard are the Gentiles and those who bicker about laboring all day are Jews who have lived in covenant with God for centuries. Throughout her work, Levine identifies many careless anti-Jewish interpretations, such as the characterization of the priest in the parable of the Good Samaritan as concerned only for ritual purity and the characterization of Jews as the actual inventors of the prosperity gospel. In analyzing the parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19-31), Levine writes: “The subtext for today’s Christians is that Jews glorified wealth and worshipped Mammon, while Jesus invented the social conscience and liberation theology” (250). She also dismisses the notion that first-century Jews ignored outcasts and worshipped an unforgiving God.

Familiar with rabbinical texts, the works of Philo and modern historical scholarship—both Jewish and Christian—on the first century, Levine not only strips away some garish Christian overlay occluding Jesus’ parables, she enriches interpretation of them. She helps Christians to recall the beauty of the Old Testament, which represents, for Christians, an essential element of the definitive revelation of God. Levine makes us aware of “residual marcionism,” a heresy that dismisses the Old Testament as crude or unworthy of the God revealed through Jesus. Imagine what first-century Jews would think when they hear Jesus begin a parable: “A man had two sons…”? (Luke 15:11) What of Cain and Abel, Jacob and Esau? The Jewish Scriptures inform the Christian contemplation of the New Testament—in fact, they must.

And so, the Catholic Book Club considers the work of a Jewish New Testament scholar in order to continue our encounter with Jesus of Nazareth.

Please offer a response to the book or some of the questions below:

1. What do you think of Prof. Levine’s interpretation of the arch-parable, the story of the Prodigal Son? How does the parable change if one removes the primacy of repentance and forgiveness that constitute the heart of most Christian interpretations of the parable?

2. Have you become aware of anti-Judaism in Christian interpretation of scripture?

3. Do we spend enough time studying and praying with the Old Testament—that library of texts that formed a people and shaped Jesus’ own religious consciousness?