Cambridge, MA. For any preacher, this Sunday’s portion of the Sermon on the Mount poses great challenges. It is quite long, a full 20 verses (Matthew 5.17-37). It is also full of difficult ideas: Jesus is the one who comes to fulfill, accomplish, the Law in its every detail. If the Pharisees are thought of as overly concerned about obeying the Law —then, Jesus says, outdo them in righteousness, neither breaking the Law nor encouraging others to do so. Not a Jesus most of us like to think about. And then there are the four examples that Jesus gives, each worthy of at least one Sunday homily: not only do not kill, but do not get angry; not only do not commit adultery, but do not lust in your heart; not only expel your wife from your house only in accord with legal restrictions, but do not do that at all; not only be honest in swearing oaths, but do not swear at all - simply tell the truth. Each of these gets complicated when we ponder its meaning for the Church and society today. Either it is obscure, or on the contrary so simple as to make us uncomfortable. Key is not to treat any of the four instances as entirely different (as if to say: the Sermon means that divorce is always wrong, but killing and getting angry, etc., can be ok.)

So it is no surprise that Swami Prabhavananda takes a full twelve pages in his Sermon on the Mount according to Vedanta to comment even briefly on this section. It may be surprising that more than half his comment is on the opening section, “Do not think that I have come to abolish the law or the prophets; I have come not to abolish but to fulfill. For truly I tell you, until heaven and earth pass away, not one letter, not one stroke of a letter, will pass from the law until all is accomplished. Therefore, whoever breaks one of the least of these commandments, and teaches others to do the same, will be called least in the kingdom of heaven; but whoever does them and teaches them will be called great in the kingdom of heaven. For I tell you, unless your righteousness exceeds that of the scribes and Pharisees, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven.” (5.17-20) But his interest in this portion makes sense when we realize that this text reminds Swami of the words of Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita, and so he fixes on them, in turn giving an unexpected teaching on the meaning of the Incarnation.

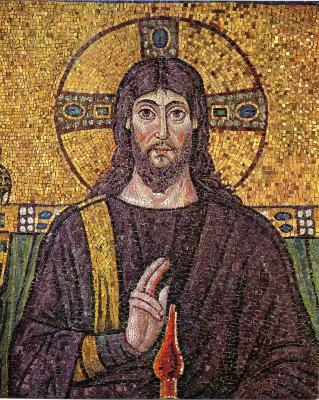

For it is here that Jesus explains why he came, the purpose of his particular avatara (descent into the world). Recall that for the Swami (and for most Hindus) there is no problem at all in recognizing that Jesus is God come into the world. The problem, as he explains here at length, has to do with uniqueness: “Christians believe in a unique historical event, that God was made flesh once and for all time in Jesus of Nazareth. Hindus, on the other hand, believe that God descends as man many times, in different ages and forms.” Even declarations of uniqueness simply remind Prabhavananda of other such declarations; Krishna says in the Bhagavad Gita, “I am the goal of the wise man, and I am the way. I am the end of the path, the witness, the Lord, the sustainer. I am the place of abode, the beginning, the friend and the refuge.” So too, Swami adds, the Buddha can be accepted as an avatara.

Why so many avataras? The world has its ups and downs, righteousness is often forgotten, neglected, and so God comes again to restore order in every particular case. In fact, Jesus’ words are reminding Prabhavananda of the famous words of Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita: “Whenever goodness grows weak, When evil increases, I make myself a body. In every age I come back, To deliver the holy, To destroy the sin of the sinner, To establish righteousness.” Yet, Prabhavananda adds, it is always the “same supreme Spirit” manifest in the avatara. He knows that Christians will resist this idea of recurrent descents of God into the world, but he suggests that we need not be afraid. As in this Sermon passage, Jesus came to teach the truth, but “if, in the history of the world, Jesus had been the sole originator of the truth of God, it would be no truth; for truth cannot be originated,” that is, begin to be true at some particular time. Interestingly, Swami supports his view by quoting St. Augustine: “That which is called the Christian religion existed among the ancients, and never did not exist from the beginning of the human race until Christ came in the flesh, at which time the true religion, which already existed, began to be called Christianity.” (from his Retractions? Oh reader, help me identify the source of the quotation!)

Prabhavananda then goes on, much more briefly, to comment on new, interiorized values — be one who is not angry, or lustful, or hard-hearted and legalistic towards one’s wife, or truthful only in accord with external words, oaths. We cannot go into detail – read it for yourself – but can only notice the main point. Righteousness is about “entering the Kingdom of Heaven,” it is a pathway to God. As we unite ourselves with God, who is beyond all “relative good and evil,” we too “transcend relative righteousness.” But the path is long, and we must first learn to “abstain from harming others, from falsehood, theft, incontinence, and greed; we must observe mental and physical purity, contentment, self-control, and recollectedness of God.” This is what Jesus is teaching by his call for righteousness greater than external observances; he is, in essence, arguing that Christian holiness begins in the same basics — external and internal discipline (yama, niyama) — that yoga teaches: the ending of anger; the embrace of chastity as a positive virtue and not simply self-denial; a simple truth-telling that needs no oaths because it is simply conformity to God: “‘Not I, not I, but thou, O Lord!’ The more we become established in this idea, the more we renounce the thought of self, the greater will be our attainment of peace.” (Swami seems to say nothing about Jesus’ command “not to put away one’s wife.” Not sure why!)

So there is much here to consider, about who Jesus is, as Teacher and Giver of a new interior righteousness. A key question for us will be whether we can learn by agreeing in part with Prabhavananda, in part disagreeing. If we want to insist that Jesus is not an avatara like Krishna or the Buddha, will we still be able to learn from the remainder of this Hindu teaching on the righteousness taught in this Sunday’s Gospel? Distinguishing the teacher and message is never easy. Which is more important? I would say the Teacher in this case, but perhaps Swami's view is not entirely foreign to what Matthew intends.

FXC: thanks!

One of my intellectual hobbies is reading about occult and New Age manifestations of Christianity, particularly when Catholic in their overall ethos, and it is surprising how often you run across this particular Augustinian retraction in that genre of literature. I had thought it was a particularly obscure text only guild-trained theologians would know anything about, so I just about fell out of my chair when I ran into it in Henri Gamache's "The Master Book of Candle Burning" (a 1940s text about candle magic in New Orleans-style voodoo - not exactly a highbrow tradition!). Since then it has turned up with some regularity in readings in "alternative/unofficial Christianity" - often enough to make one seriously wonder why. It cannot be that everyone is a guild-trained comparative theologian who was exposed to the text as a part of their professional training, as these are not professional theologians, and their writings generally predate the popularization of that text in our field.

I suppose it's just that the text answers a theological need which is perhaps not generally recognized by "official" exponents of Christianity such as priests and scholars, but is deeply felt in some "unauthorized" Christians traditions. Once writers in these genres encounter the quote, they latch onto it and propagate it, because it meets a need - just as comparative theologians have done the same thing to meet our needs. The same thing is probably true of Prabhavananda's use of the text. (Sidebar: have you ever read Swami Abhedananda's "Why a Hindu Accepts Christ and Rejects Churchianity"? It doesn't use Augustine's text as far as I know, but it is theologically learned and very interesting).

The need seems to be to get around an overemphasis on Christ's historical uniqueness in the mainstream tradition - and I would suspect if "real" people are continually having to get around this overemphasis, maybe it isn't a tenable theological position in the first place, but rather a closely-guarded jealousy of theological elites.

In other words, maybe theology (folk and otherwise) greatly needs Augustine's Retractions or even more radical ideas about Jesus as a non-unique avatara who descends when he is needed in whatever form he is needed, and could take a cue from Vedanta strategies for re-interpreting Krishna's claims to uniqueness for interpreting similar claims to uniqueness in the NT and the Christian tradition.

Just some thoughts. Thanks for this post - I think it gets out some of the best material in Prabhavananda's book.

http://books.google.com/books?id=cMcaAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA483&lpg=PA483&dq=why+a+hindu+rejects+churchianity&source=bl&ots=vSFQASWPgG&sig=N44YfZ0Wx9ncwMo35Ij3szFeIqM&hl=en&ei=P9NWTencBoW4twf1uJn-DA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=7&ved=0CDsQ6AEwBg#v=onepage&q=why%20a%20hindu%20rejects%20churchianity&f=false

"That which is known as the Christian religion existed among the ancients, and never did not exist; from the beginning of the human race until the time when Christ came in the flesh, at which time the true religion, which already existed began to be called Christianity. (Retractt. I, xiii, cited by Dr. Alvin Boyd Kuhn in hisShadow of The Third Century, Elizabeth N.J.: Academy Press, 1949, p.3.)"

http://www.egyptcx.netfirms.com/augustine_cx_before_christ_egypt_origin.htm

FXC: thanks!

Stephen Burgard, author, (Hallowed Ground, Plenum 1997)