He Believes

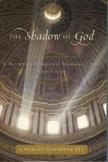

A memoir written by someone not quite a public figure and still a rather young man may not seem compelling to the general population, but Charles Scribner’s spiritual-literary-artistic autobiography will at least claim the attention of those who gratefully remember the wonderful New York publishing house that bore his family name, now lamentably defunct as an independent entity. Still in the publishing industry, Charles Scribner III (great-great grandson of the founding publisher) received his professional training in art history, focusing on the Baroque period. Indeed, one of the best essays I have ever read on a single painting by Caravaggio was written by Mr. Scribner, and his very fine volume on that other great Baroque artist, Bernini, is one that I regularly consult. Hence I was rather curious to find out more about the faith life of a Baroque art historian. Is it, well, Baroque?

The quick answer to that question is, fundamentally, yes. As in the 17th-century Baroque world, the aesthetic dimension is central to Mr. Scribner’s religious experience and the practice of his faith. Furthermore, his aesthetic standards are principally those established by the premodern European masters of ecclesiastical art and architecture, especially, though not exclusively, Baroque. Having said this, I must add that Mr. Scribner’s brand of Catholicism, while essentially conservative (especially liturgically), is by no means fundamentalist or blindly dogmatic. It is instead marked by some genuinely liberal beliefs, such as the need for a truly inclusive Christian ecumenism and the granting of a real leadership role to women in the church.

Written in the form of a year’s worth of diary entriesfrom Epiphany to Epiphanythat weave back and forth between past and present, The Shadow of God has as its primary goal to describe the author’s conversion, in his earliest adulthood, from high-church Episcopalianism to even higher-church Roman Catholicism. Though his conversion took place during the late 1960’s and early 1970’sapparently, by the way, without any dark night of the soul or other emotional upheaval, as we find in many conversion storiesit is in substance an old-fashioned, pre-Vatican II, conservative and, above all, a literary-aesthetic experience. It was highly influenced, furthermore, by a narrow circle of mostly Anglo-Saxon spirits of good cultural pedigree, like Evelyn Waugh, St. Thomas More (the Hollywood version thereof), Graham Greene and, of course, C. S. Lewis. But unlike the story of Dorothy Day, whose Long Loneliness is a classic in the literature of Catholic conversion stories, Mr. Scribner’s account of his attraction to his new faith has nothing to do with Jesus the champion of the poor and the oppressed. That Jesus would appear nowhere on his radar screen.

While recounting his conversion and the unfolding of his personal life (marked by every social and economic privilege), Mr. Scribner offers sensitive discourses on the beauty and meaning of his favorite works of art, literature and music. These portions will delight those whose tastes coincide with his, namely, Rubens, Shakespeare, Mozart and the other greats from the Western canon. Others, instead, will find these sections parochial and stuffy.

The same, however, cannot be said for Mr. Scribner himself, whom I have never met or had any sort of personal contact with, but who comes across as a thoroughly likeable, kind, decent human being, a loving son, father and husband as well as a loyal, caring friend. He is also a good storyteller: one should be so lucky as to be seated next to him at a long, formal dinner. Though the book is replete with references to many famous personalities of the social, literary, academic and musical worlds who populate his personal life, readers should not expect any juicy gossip or revealing behind-the-scenes anecdotes about these figures. Scribner is too much of a gentleman for that sort of thing.

Returning to the central question in this book of aesthetics and religion, I can well sympathize, as a lover of much of the same art, architecture and music as the author, with his point of view; but unlike him, I am extremely suspicious of its use as a measure of religious authenticity or ecclesiastical truth. While it can at times be powerfully suggestive of the divine, mesmerizing aesthetic beauty can just as easily be misleading. Domenico Bernini, son of Scribner’s beloved artist Gian Lorenzo, remarked of his father’s artistic/theatrical talent that it made what was in substance finto’ [fake, or artificial] appear true. This does not apply only to the art of Bernini. We have a good example of it in The Shadow of God. Scribner speaks often of the great aesthetic beauty of his parish church, St. Vincent Ferrer in New York City, one of those well-endowed parishes that the late Catholic actress Rosalind Russell (who makes a brief appearance in the book) would have nicknamed, as she did her own L.A. parish, Our Lady of the Limousines. St. Vincent Ferrer is arguably one of its city’s most beautiful Catholic edifices, but its beauty belies the fact that it is dedicated to one of the most unattractive saintsa fanatical, apocalyptical preacher whose fiery word played a shameful role in the tragic history of Catholic anti-Semitism in Europe.

Yes, as Mr. Scribner points out, beautiful works of art nourish religious faith and spiritual growth. But they can also deceive us and camouflage what is not wholly religious or truly spiritual. Let the believer beware.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “He Believes,” in the June 5, 2006, issue.