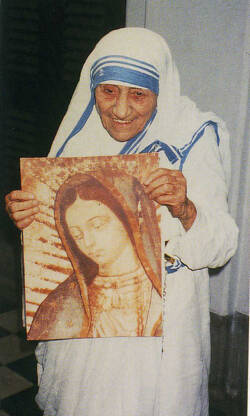

It is not hard to come by images of the holy in Tijuana. But in a modest building there a group of Sisters in white saris with three blue stripes cherish a wonderful two-for-one: a newspaper photo of Mother Teresa of Calcutta beaming delightedly as she holds in her hands an image of Our Lady of Guadalupe. The photograph reminds us of Teresa’s history in Tijuana, and of her joyful relationship with Latin America as a whole.

The Blessed Mother Teresa—born 102 years ago in August, died 15 years ago in September, beatified nine years this October—founded her order, the Missionaries of Charity, in India. But as soon as the Missionaries were allowed by church law to expand beyond India, the very first place Teresa went—at the invitation of the local bishop—was to Cocorote in Venezuela’s Zona Negra.

Over time she was invited into almost every Latin American country, starting with Mexico in 1976, El Salvador in 1977, Argentina and Panama in 1978, Brazil, and Peru in 1979. By the time of her death the Missionaries had foundations in 65 cities and towns from Santiago, Chile, north to Tijuana—as well as in areas with large Latino populations in the United States.

In Venezuela the sisters proved their versatility. In India they had dealt in situations of abject urban poverty. Now the hermanitas found themselves addressing rural needs, jouncing from campo to tiny campo in a jeep on donated gasoline, saris fluttering. They offered their trademark assistance to the poor, the young and the dying. But they also brought holy communion to those who needed it in priestless villages, worked to unite divided families, and even toiled as roofers when a large storm struck the area. They mediated between long-term town residents and migrants fresh from the mountains looking for work. Teresa’s friend and biographer, Eileen Egan, reported a visiting Teresa sitting happily with a group of migrants who sang:

Como granas que han hecho el mismo pan,

Como notas que tejen un cantar,

Como gotas de agua que se funden en el mar,

Los christianos un cuerpo formaran.

She insisted not only on helping the poor, but also on accompanying them through their struggles—visiting daily, tending them and simply being with them. She had learned this first as a child, tagging along with her mother, who did a circuit among the destitute in her native Skopje, Macedonia, visiting, among others, an alcoholic named File, whose sores they cleaned. Teresa’s first rule for her order made this an obligation: not just the aiding of the most unfortunate, but "visiting them assiduously" and "living Christi's love for them." That theology was particularly central to her homes for the dying. Unsqueamish about death, of which she saw so much, she honored the dignity in each life she cared for, up to and including the moment of extremity. Said a man in one of her Indian hostels, "I have lived like an animal on the street. But I die like an angel, loved and cared for."

Madre on the Move

Mother Teresa was especially sensitive to the needs of people on the move. She herself had come to the Indian megalopolis of Calcutta from her native Macedonia at only 18. For 17 years she taught there as Loreto nun. But at age 36, on a long train journey to a retreat, she received the first of several locutions and visions in which Jesus spoke to her at length, telling her to “be my fire of love among the poor, [or as Teresa later put it herself, “the poorest of the poor”], the sick, the dying and the little children.” Upon her return she petitioned the church for permission to form a new order, now called the Missionaries of Charity. Two years later she moved into the slums to live out her call.

But who were the “poorest of the poor” in a city filled with the poor? One early focus was Calcutta’s main train station. Hindu/Muslim tensions and the resulting creation of the state of Pakistan had put millions of people on the roads, and turned the station into a gigantic displaced persons camp overflowing with refugees. It was to serve these desperate arrivals that Teresa established many of the schools, women’s and children’s homes, and hospices that became models for all she did later. And since refugees are often among the poorest wherever one goes, she inevitably became expert in their needs. By her last two decades she was almost stateless herself, flying from one country to the next, establishing houses so that her sisters—in a kind of sweet irony—could be permanently available.

The flip side of aiding the poor was that Teresa often found herself negotiating, and sometimes facing down, the powerful. She first visited Mexico City in 1975 to attend the International Women's Year conference (although she managed to spend a day in the depressed Nezahualcoyotl municipality.) At her hotel on the way to the airport, the phone rang: it was a summons to visit then-President Luis Echeverria, who invited her to work in Mexico. Relations between Echeverria's party and the Catholic Church were strained, and Teresa explained that she could come only if invited by the head of the local church. Echeverria agreed, the proper invitation arrived and the sisters set up their first Mexican home: next to the huge Borda de Xochiaca landfill, living and working among the garbage pickers.

Another encounter was captured in Anne and Jeanette Petrie’s 1986 documentary "Mother Teresa." After the devastating earthquake of 1976, the Guatemalan government (according to the film) offered Teresa a central location for a home for the dying; but we see a woman who appears to be a Guatemalan official telling Teresa the area is needed for a market. "Well," Teresa responds, "We are the best market. We are selling love." The official replies, "You are selling love for the poor, but there are a lot of people trying to get OUT of the poor..." Teresa objects, "But they must have much other land somewhere else." "Yes," says the official, "but this is the very center of the plaza. You could have a lot of land but not in this plaza..." Teresa cuts in. "No," she says. "I would prefer we remain where we are." She pauses. "If it is not possible, it is not the will of God for us." The next thing we hear is a voiceover by Teresa: "Ultimately, they gave us the land for 50 years, and extra land also. We have been praying and praying, 'We are gong to have to let Jesus do it.' And he does it in a beautiful way.’"

Some activists at the time were intent on alleviating poverty by political change. Teresa was not one of them. She explained that her calling was to address individuals rather than structures. However, by example, she addressed the huge gap between haves and have-nots. And to the haves, she said "We have to dive into poverty; live it, share it.

A Saint of the Ordinary

The bishops in Tijuana invited the Missionaries in February of 1988, and sisters arrived within a week. A few months later Missionaries of Charity Fathers, priests called to support the order, arrived; Tijuana is now their headquarters. Next a house of contemplative sisters. In the 1990s, as the number of people passing through on their way to the United States swelled, the bishop requested their presence at the central bus station. The sisters set up a soup kitchen, a house for abuelitos and a shelter for men staying temporarily before moving on. Eventually the order built a shrine to Mother Teresa in the city. To the right of the altar is a large statue of Blessed Mother Teresa; to the left, another of Our Lady of Guadalupe.

Teresa opened houses in almost every country in the world, became a beloved symbol of selfless love even to non-Catholics, and won the Nobel Peace Prize. After her death the Vatican waived one of its rules so that the cause for her sainthood could begin immediately. In 2002 she was found to have possessed “heroic virtue,” not just because of her service “to Christ in the distressing disguise of the poorest of the poor,” as Pope John Paul II quoted her, but also for her fidelity despite what turned out to have been a decades-long “dark night of the soul” comparable to those of great spiritual pilgrims like St. John of the Cross. Her postulator, Fr. Brian Kolodiejchuk, has also stressed her importance as a highly “imitable” “apostle of the ordinary,” who understood that great love does not require grand gestures, but can be realized person-to-person, one by one. Or, as Kolodiejchuk (himself based in Tijuana), puts it in Spanish, “Cosas ordinarias, amor extrordinario.”

Later in 2002, the Vatican announced Teresa's intercession in the miraculous 1998 healing of a woman in India. For recognition as a saint, a second miracle must be validated. Kolodiejchuk is currently sifting through some 4,200 reports of supernatural favor thanks to her intercession, 700 received in the last two years. Befitting Teresa’s activity in Latin America, Kolodiejchuk reports that the most active current investigations is in Colombia.

She was a foundress, a profound mystic and yet as down to earth as her face, its ever-present smile wreathed by wrinkles etched by the sun. She was from everywhere and nowhere, and she imposed her will on nobody, but everybody. Her power lay not in hierarchy or celebrity, but in the urgency of her call to the poorest poor, wherever they are. That urgency is no less compelling—in Guatemala City, Los Angeles, Chicago, Washington D.C. or for that matter Rome—as we remember her now.

Photos courtesy of the Missionaries of Charity.