A Dwelling Place for God

As Christmas approaches, the readings for the Fourth Sunday of Advent focus our attention on the notion of a dwelling place for God.

In the first reading, King David finds himself free, in that he no longer has to fight his enemies. Instead, he can devote his energy to whatever he likes, so he plans to build a beautiful palace for himself and a splendid temple for God. At first the prophet Nathan approves this plan, but then he hears a word from God that turns the plan upside down: “Should you build me a house to dwell in?” God explains that all the success David has had is God’s doing, which now culminates in God’s establishing a house, that is, a dynasty, for David. There is a play on the word “house,” as it shifts in meaning: from David’s palace to God’s temple to the Davidic ruling line. Underlying the text is a criticism of the monarchy.

In the verses omitted from the Lectionary selection (vv. 6-7a), God objects that YHWH has never asked any of the leaders of Israel to build a temple: “I have not lived in a house since the day I brought up the people of Israel from Egypt to this day, but I have been moving about in a tent and a tabernacle.” God has been on the move, dwelling with the Israelites in the same way they themselves have lived—in makeshift tents as they traversed the desert between Egypt and Canaan. And God has been present in a portable tabernacle that they carried with them wherever they sojourned.

In the Gospel reading for the last Sunday of Advent, Gabriel’s message to Mary is that God now takes up residence in human flesh.

The message is brought to fulfillment in the Christmas readings. The Gospel for Christmas day, the Prologue of John’s Gospel, reaches its high point with v. 14, “and the Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us.” The Greek verb eskenosen literally means “pitched his tent.” God’s predilection is to dwell with human beings in their ordinary dwellings and in their same human flesh. While there is a place for magnificent temples and churches where we can gather as a people to glorify God, the Holy One would have us first recognize that divinity walks around in our midst in human skin.

Moreover, those who are least impressive by human standards are the most favored by God when it comes to revealing God’s mystery. David, for example, was the youngest, least qualified son, when God took him from pasturing sheep to lead his people. Mary was an ordinary young woman making wedding plans in an insignificant little town in Galilee, when she was asked to take on a seemingly impossible role.

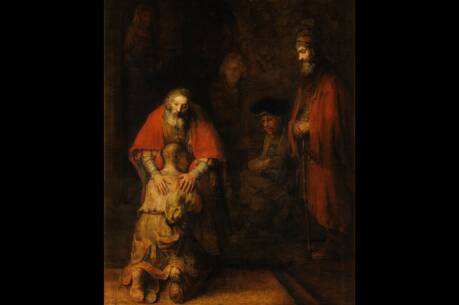

In both the first reading and the Gospel for the Fourth Sunday of Advent, there is a startling twist: it is not we who make dwelling places for God, but God who builds the house. Likewise, on Christmas day, John’s Gospel speaks not only of how wondrous it is that God takes on the form of a human child, but also of how our reception of the Word enables us to become children of God. We keep on becoming a child of God by receiving this lowly child, not only the one in the manger, but all those who seem insignificant all around us.

The scene of the annunciation to Mary is a subject of much Christian art. Oftentimes Mary is portrayed as serenely praying and surrounded with light and joy. But in other annunciation scenes there is an undercurrent of distress, incomprehension and scandal in this story. Henry Ossawa Tanner captures this sense in his painting, “The Annunciation,” in which Mary sits at the edge of her disheveled bed, with a look of puzzlement and concern, while gazing toward a golden beam in the form of a cross. Megan Marlatt’s fresco “The Annunciation” in St. Michael’s Chapel at Rutgers University likewise depicts the topsy-turvy aspect of the event, as the angel appears upside down, uttering the word “Blessed” backwards. Mary’s life, as she thought it would be, is entirely upended, which is greatly troubling.

What God is asking is incomprehensible. Mary questions how it can be. In addition, in her tiny village, where everyone knows everyone else and many people are related to one another, everyone knows that she and the man who is already her legal husband have not yet begun to live together. But all of them can count to nine. What will they say about her, what kinds of nasty looks will they cast her way when her precious child is born too soon?

While not spelling out how, Gabriel reassures Mary that in the midst of this messy situation, God will bring forth blessing, holiness and salvation for all. Twice God’s messenger assures her that she is grace-filled and is favored in God’s sight, even if others will question this. He also reassures her that she is not alone. Her relative, Elizabeth, will help mentor and support her. Without knowing how God will accomplish all this, Mary opens a space for God to dwell within her, enabling the divine to make a new home within all humankind.

Mary makes a physical home for the Holy One in her womb; hers was a unique role. But we too are asked by God to make a dwelling place within ourselves and within our world for the Christ. The circumstances are always messy. It is not in glorious buildings beautifully adorned but in the humblest of persons, in the most difficult of circumstances, that God takes up residence. The irony is that in trying times we may feel abandoned by God, or question why it is that God is punishing us, or why we have lost God’s favor. It is precisely in such times that God dwells most intimately with us, assuring us that we are full of grace and favor, asking us to trust that God can and will bring forth blessing, even if we cannot see how.

Many of our ancestors in the faith were called “favored” by God: Noah (Gn 6:8), Moses (Ex 33:12-17), Gideon (Jgs 6:17) and Samuel (1 Sm 2:26). God always asks a great deal of “favored” ones. Moses, for example, found it so burdensome at one point that he prayed God would do him the “favor” of killing him at once, so he need no longer face the distress of leading a difficult people (Nm 11:15). Mary is right to be troubled when Gabriel calls her “favored” one.

But God’s “favor” is also accompanied by God’s power and protecting Spirit. Jesus, too, has “the favor of God” upon him (Lk 2:40, 52), a favor that extends to all who receive him, as John’s Gospel says in the Christmas reading: “grace upon grace,” or “favor upon favor” (Jn 1:16). Likewise, in the Gospel for Christmas Midnight Mass, the shepherds sing of the peace now manifest for all those favored by God (Lk 2:14)—that is, all who make room in their “inns” for this unlikely Coming One.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “A Dwelling Place for God,” in the December 15, 2008, issue.